This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Marisa Lagos: From KQED, this is Forum. I’m Marisa Lagos, filling in for Mina Kim.

The rapid development of generative artificial intelligence has sparked both excitement and trepidation. But in some sectors, it’s hardly hypothetical anymore. According to OpenAI, more than 40 million people ask ChatGPT a health care–related question every day. Doctors and health care systems are already using AI to help transcribe notes, answer clinical questions, write insurance authorizations, and, in some cases, even diagnose patients.

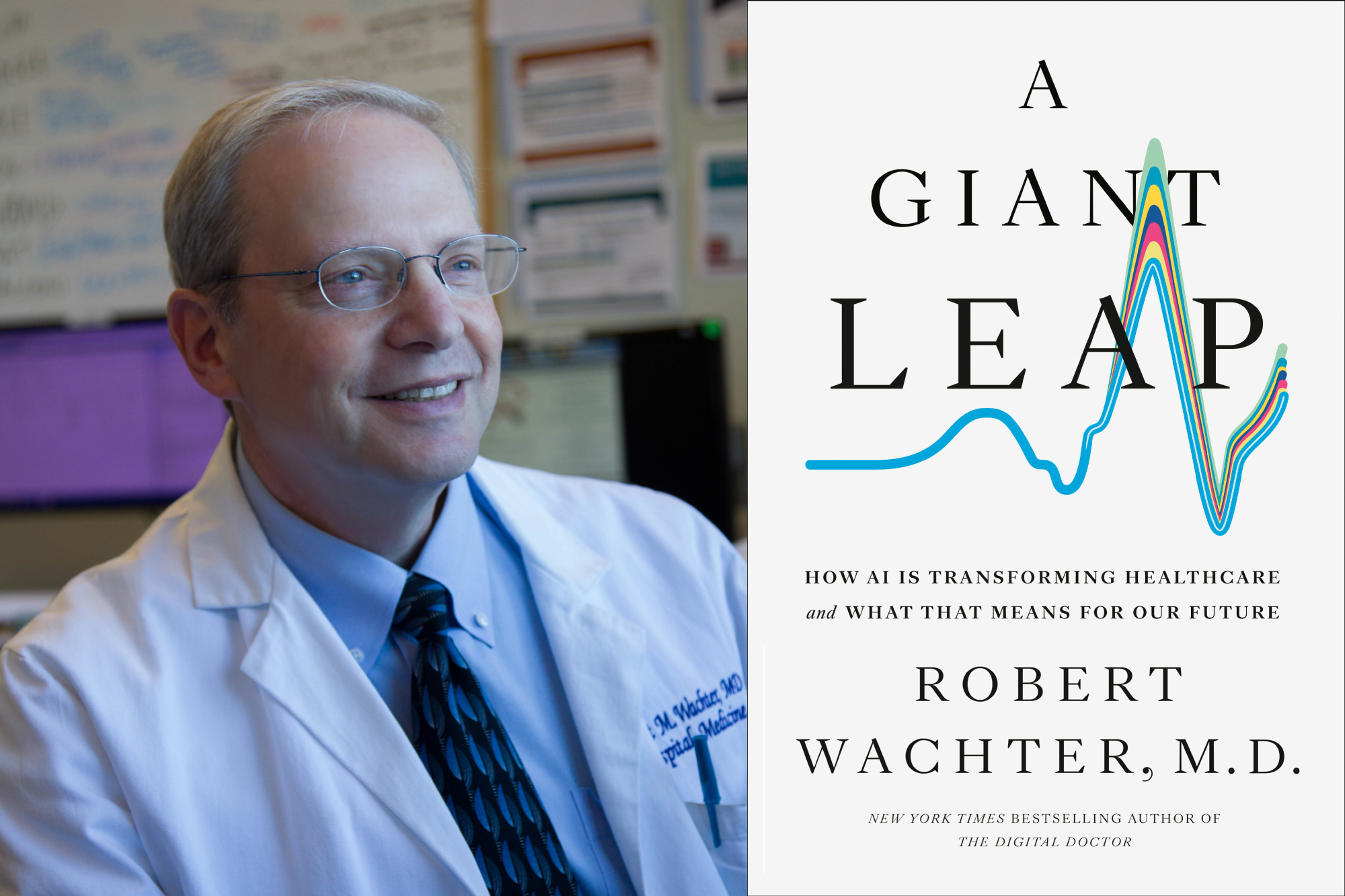

Our guest today sees this as an exciting and necessary development that could transform medicine for providers and patients alike. Dr. Bob Wachter of UC San Francisco is a legend in hospital medicine — someone we returned to again and again during the COVID-19 pandemic. His day job is professor and chair of the Department of Medicine at UCSF, and his new book is A Giant Leap: How AI Is Transforming Health Care and What That Means for Our Future.

Dr. Wachter, welcome back to KQED Forum.

Dr. Bob Wachter: Thank you, Marisa. It’s a great pleasure to be here.

Marisa Lagos: I want to spend most of this hour talking about your book and AI, but since we have you, I do want to check in first on some of the latest news in health care and medicine. It’s been quite a year already, and it’s only February.

Dr. Bob Wachter: Right.

Marisa Lagos: And I want to tell our listeners, if you have questions for Dr. Wachter about vaccines, diseases, or the health care system, this is your opportunity. We’ll move on to AI in about 20 minutes. You can call us now at 866-733-6786.

So, big picture: you’re the chair of medicine at UCSF. We’re seeing huge potential changes from the policy bill passed by Republicans last year, affecting Medicare, Medi-Cal in California, and ACA subsidies. Are you seeing those effects on the ground yet at UCSF?

Dr. Bob Wachter: Not yet. The big thing we struggled with last year was the threat of massive cuts to the NIH budget.

Marisa Lagos: Right.

Dr. Bob Wachter: UCSF is one of the great research institutions and is quite dependent on federal funding. The proposals were to cut the NIH budget by 40 percent and to cut so-called indirect costs — the money we get to run the research enterprise — by something like 80 percent. That would have been apocalyptic.

Congress, for one of the only times I’ve seen, really stood up to the administration. The bill that just passed keeps NIH funding fairly stable. So, interestingly, not bad. I think many of us were hoping the country would say, “We really want medical research. We want to find cures for cancer and Alzheimer’s,” and in the end, that went okay.

The proposed cuts to Medi-Cal and Medicare are still in the works. We’re projecting their effects and preparing for what happens when more people don’t have insurance. But right now, those cuts haven’t fully hit yet.

Marisa Lagos: One thing that is moving forward is the new childhood vaccine schedule, under Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now head of Health and Human Services. How are you thinking about this as a clinician and as a leader in a health care system? I know some Western states are creating their own vaccine advisory boards. Who are you listening to at this point?

Dr. Bob Wachter: Unfortunately, not the CDC and not the administration. The vaccine schedules that existed until about a year ago were put together by world experts in vaccines and infectious disease. They were evidence-based and carefully vetted.

What’s coming out now is not. It’s being driven by ideology. Because of that, they’ve lost my trust — and the trust of many experts in the health system. I hope people will still have access to vaccines the way they did before.

I’m thinking about this not only as a health care leader but as the grandfather of a two-year-old. I believe she should have — and has received — the vaccines that were recommended prior to these new rules. It’s very worrisome. I don’t understand why people would want young children not to receive vaccines that keep them healthy, but there’s clearly an ideological agenda at play.

It’s important that patients ask their doctors and find trusted sources — which, unfortunately, no longer include the federal government.

Marisa Lagos: Are you seeing a decline in childhood vaccinations or other vaccines in your practice?

Dr. Bob Wachter: We’re beginning to, but not dramatically. One thing I learned during COVID is that living in the Bay Area is a privilege — and we live in a bit of a bubble.

Most people here pay attention to the science, trust expertise, and trust institutions like UCSF. So we’re not seeing massive drop-offs yet. But in other parts of the country, colleagues tell me this is a daily battle. Patients come in saying they don’t want a vaccine because they heard it causes autism or could kill their child. Having that conversation ten times a day is exhausting.

Marisa Lagos: Unfortunately, we’ve seen outbreaks of diseases we hadn’t talked about in a long time. There’s been a tuberculosis outbreak at Riordan High School in San Francisco — three active cases and about 50 latent cases. They’re mostly doing virtual classes now. What do you make of that?

Dr. Bob Wachter: TB is really its own thing. There’s no vaccine for tuberculosis. I think this one is just bad luck.

There’s a tendency to blame every bad outcome on policy, but this is different. We’re still a nation of immigrants, and occasionally people arrive with diseases like TB. At UCSF, we periodically see TB cases and sometimes small clusters.

With measles, you can clearly connect outbreaks to vaccine policy. TB hasn’t gone away in the same way. So I see this as unfortunate but likely a one-off.

Marisa Lagos: Given the number of latent cases, should people connected to the school be tested?

Dr. Bob Wachter: I would trust what public health officials are doing. I don’t know enough about the specifics to second-guess them. In general, if there’s exposure to TB, people should be tested because latent TB can reactivate later in life, especially with age or immunosuppression. I’m sure there’s an appropriate testing regimen in place, and I’d follow that guidance.

Marisa Lagos: It’s jarring to hear about a TB outbreak in San Francisco. Congregate settings clearly complicate things.

You mentioned measles. We’ve seen several cases in Southern California tied to international travel. As someone with a young grandchild — and I have a one-year-old nephew — how should people be thinking about risk? Should families be more cautious about places like Disneyland, or just live their lives?

Dr. Bob Wachter: It gets exhausting. During COVID, people constantly asked themselves: Do I go out to dinner? Do I visit my elderly parents? After COVID subsided, it was liberating not to think about those things all the time.

It would take a pretty severe outbreak for me personally to return to a masking-everywhere mindset. Life involves risk — crossing the street, going into crowds. If you obsess over it, you’ll drive yourself crazy.

The best protection against measles is vaccination. It’s not 100 percent, but the real protection comes when everyone is vaccinated. Unfortunately, we may be moving into a world where the best you can do is make sure you and your loved ones are protected as much as possible.

Marisa Lagos: How much do you think the politicization of COVID contributed to the rise of figures like RFK Jr. and the anti-vaccine movement?

Dr. Bob Wachter: There’s been a broader trend in American society toward distrust of expertise and institutions. Social media amplifies that — everyone has a megaphone, and influencers often outweigh actual expertise.

COVID forced society to grapple with tough trade-offs between individual freedom and public health. In a country that values individualism, backlash was inevitable. What frustrates me is the revisionist history that claims everything we did was wrong because COVID wasn’t that bad. More than a million people died. That’s not trivial.

Some decisions were wrong — schools were closed too long, for example — but most decisions were reasonable based on what we knew at the time. It’s sad that COVID is now cited as proof of government overreach and expert incompetence.

People ask whether we’re safer now if another pandemic hits. I think we’re less safe. Early in COVID, fear made people willing to sacrifice for safety. Next time, I worry resistance will emerge immediately — and that’s scary.

Marisa Lagos: Just a minute before the break. Noelle asks: with such low levels of COVID this winter in the Bay Area, is COVID becoming more of a summer disease?

Dr. Bob Wachter: COVID’s seasonality is still odd. It hasn’t settled into a clear winter pattern like the flu. We often see both summer and winter bumps. The best approach is to watch wastewater data and adjust precautions accordingly.

Marisa Lagos: And there’s plenty else circulating — colds, flu, everything.

Dr. Bob Wachter: Exactly.

Marisa Lagos: As someone with two young kids, I see it all.

Dr. Bob Wachter: You see it all.

Marisa Lagos: We’re talking with Dr. Bob Wachter of UCSF. After the break, we’ll get into his new book, A Giant Leap: How AI Is Transforming Health Care and What That Means for Our Future.

If you have questions about AI and health care, email forum@kqed.org, find us on social media @kqedforum, or call 866-733-6786.