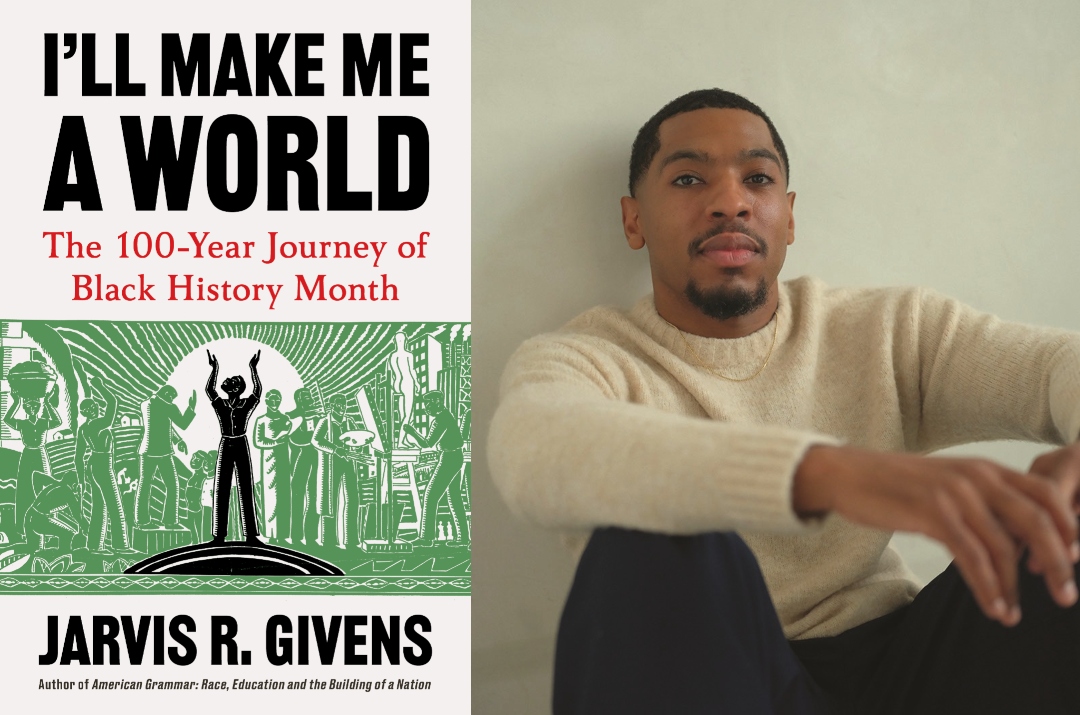

This February marks 100 years of celebrating Black History month, which began as just a week in 1926. Now, as political efforts to scrub Black history from American classrooms intensify, historian and California native Jarvis Givens joins us to talk about his new book, “I’ll Make Me a World: The 100-Year Journey of Black History Month.” Givens says the act of preserving Black stories has always been political, always been about power, and always been a tool for liberation. Has learning Black history shaped the way you see America?

Historian Jarvis Givens on Who Made Black History

Guests:

Jarvis Givens, professor of African and African American studies, Harvard University. His new book is "I’ll Make a World: The 100-Year Journey of Black History Month."

This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Rachael Myrow: From KQED, this is Forum. I’m Rachael Myrow, in for Mina Kim.

This month, we mark a century of formal Black history celebrations, which started with a week in 1926. Today, as political battles over curriculum rage in state legislatures and local school boards, the question of whose history gets told—and how—has never been more relevant.

Historian Jarvis Givens joins us today to talk about his new book, Tracing the Evolution of Black History as a Formalized Study. Dr. Givens, thank you so much for joining us.

Jarvis Givens: Thanks for having me, Rachael.

Rachael Myrow: You were born and raised in Compton. I thought we might start with you telling us about your preschool teacher, Ms. Myron Ruth Butterfield. What was it about the way she taught Black history that lit a spark in you all those years ago?

Jarvis Givens: Yeah, I appreciate the opportunity to go back and think about my early introduction to Black History Month. I consider Ms. Butterfield to be my first teacher of Black history. She was my preschool teacher at a small parochial school I attended in Compton, California. It was an independent, all-Black school with all-Black teachers. It had formerly been an all-white school when Compton, as a city, was all white.

Ms. Butterfield, like many of the teachers I encountered there in the early ’90s, was a Southern migrant. Many of them were educated in the Jim Crow South. She later shared with me that she had experienced early iterations of Negro History Week in the schools she attended while growing up in Grenada, Mississippi.

So when I was her student in 1992 and 1993, and we were preparing for my first Black History Month program, it was something that was taken very seriously. I’ll never forget our task—my preschool classmates and I were required to memorize excerpts from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

I remember rehearsing and taking the rehearsal so seriously, with Ms. Butterfield emphasizing how we put emphasis on particular words and how we expressed the emotions surrounding that speech. I’ll never forget the triumphant, fearful feeling my classmates and I had when we delivered our speeches in front of our family members, community members, and the older students at the school.

That became an annual experience for me—these really grand, serious Black History Month programs. African American history and culture were integrated throughout the school’s academic culture all year long, but Black History Month became a time for us to display for our community and families what we had been learning about ourselves, our culture, and the inspiring lessons from Black people who had done important things in generations past.

Rachael Myrow: That’s such a great, evocative illustration. When you visited her again in 2019, she talked about creating a Black History Month program in 1993 and about her own education in the Mississippi Delta. How was that exchange also a turning point for your understanding?

Jarvis Givens: That conversation was such a gift. Ms. Butterfield came into early childhood education later in life, so she was much older than many of the other teachers at the school. She was born in 1939 into a family of tenant farmers just outside Grenada, Mississippi.

She carried with her memories of the inspiring education she received in segregated Black schools—a story that’s not often told. Those schools faced deep inequities: fewer resources, lower teacher pay. But there was also incredible work happening because of the commitment of the teachers.

She brought that same commitment to her work with me. When I sat down with her in 2019 to ask about her educational journey, before I even brought up the Black History Month program that my family still remembers so vividly, she talked about experiencing Negro History Week as a student. She remembered learning about figures like Phillis Wheatley and Booker T. Washington—Black people who had done important things for their communities.

She told me that this was something she always carried with her and wanted to pass on to us. That conversation helped me understand my work today—as a historian, and in working with young people—as part of a much longer legacy. Seeing myself as connected to a tradition she introduced me to, one that I now study and write about, was incredibly meaningful. It helped me see Black history education as something sustained for more than a century through care, commitment, and community.

Rachael Myrow: Sorry to bounce around your childhood now, but let’s dial it back to third grade. You include a passage in the book about your first experience learning about Nat Turner.

Jarvis Givens: Yes. This was another teacher at the same school in Compton—St. Timothy’s Episcopal Day School. It was all Black students and all Black teachers, though very few of us were Episcopalian.

My third-grade teacher, Ms. Shirley Topman, was also a Southern migrant. This was my first encounter with the 1831 insurrection led by Nat Turner in Southampton, Virginia. There’s an excerpt on page 93 that I’d love to read.

Rachael Myrow: Yes, please do.

Jarvis Givens: I remember when I first learned of Nat Turner’s story, including his death and dismemberment. I was in third grade, and my class was preparing for our school’s annual Black History Month program. Turner became the center of a lesson in my third-grade classroom as a Black folk hero when Ms. Shirley Topman, an African American teacher from North Carolina, told my classmates and me his story after becoming concerned that we were not taking our rehearsal seriously.

Sitting at her desk, she gave us an impromptu lecture on Turner. I can still see the big picture window immediately behind her, through which was visible the school’s rear playground featuring a blue metal swing set, monkey bars, and the tall iron jungle gym we loved to climb during recess.

To contextualize our assignment—which was to memorize Eloise Greenfield’s poem about the “Night Flyer,” Harriet Tubman—Ms. Topman explained how our freedom had been bought and paid for by people whose lives we were commemorating. She insisted that we remember and study their bravery, their courage, and their collective struggle, and that we be inspired to put some of what we learned into practice in our own lives.

She stressed that the world they lived in, and the world we had inherited, could be quite hateful toward Black people. Nat Turner’s story, she told us, was evidence of this.

That was my first time hearing Turner’s name, and I would never forget it. Turner wasn’t just killed after fighting to free the enslaved, Ms. Topman explained. She looked at us as she dragged her nails, covered in gold polish, down her outstretched arms, describing how parts of his body were taken. They made purses, hats, and clothes from his skin.

I remember thinking such a thing could not possibly be true. I had previously learned something about the violence experienced by enslaved people, but this story was not just violent—it was evil in a way my eight-year-old mind could not grasp.

It would be some time before I fully understood how such disregard for human life was part of maintaining social hierarchies between enslaved and free, between Black and white, in the United States. The lesson embedded in Ms. Topman’s lecture I would only grasp decades later.

For some reason, I carried my skepticism of her story into adulthood. Even as a child, I knew she was prone to dramatics. Her stories, though true, felt embellished. I was shocked, and slightly ashamed, to learn as a graduate student that Ms. Topman had indeed been telling the truth.

To this day, Greenfield’s poem occasionally pops into my mind, reminding me that Harriet Tubman “didn’t take no stuff, wasn’t scared of nothing either, didn’t come in this world to be no slave, and wasn’t gonna stay one either.”

Rachael Myrow: This passage really gets to what I think is the central question of this book: How do we educate Black children in America today about their history—American history—without driving a stake through the heart of their hope?

Jarvis Givens: One through line in the lessons I learned about Black history, even when they were brutally honest, was an emphasis on Black agency. Black people were never presented as merely victims of violence. They were creators, organizers, and visionaries—constantly imagining and working toward a more beautiful world.

We need to be honest about the full range of Black experiences, which means telling the truth about both the terrible and the beautiful. That honesty can still be hopeful and future-oriented. We study the past to make sure horrors are not repeated, but we also focus on the courage, creativity, and commitment of people who, despite unimaginable circumstances, kept pushing toward more freedom, more justice, and more beauty.

Rachael Myrow: We’re talking about the preservation of Black history on February 2nd, as part of Black History Month, with Dr. Jarvis Givens, professor of African American Studies at Harvard University. His new book is I’ll Make a World: The 100-Year Journey of Black History Month.

How do you honor or observe this month? What does Black history mean to you personally? Whatever you do, stay with us.