This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Mina Kim: From KQED, welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim. The science of memory manipulation is farther along than you might think. Scientists have been able to weaken or erase memories — even implant new or false ones — in mice, inspiring sci-fi storylines in films and series like “Severance:”

“I acknowledge that henceforth, my access to my memories will be spatially dictated. I will be unable to access outside recollections whilst on Lumen’s severed basement floor, nor retain work memories upon my ascent.”

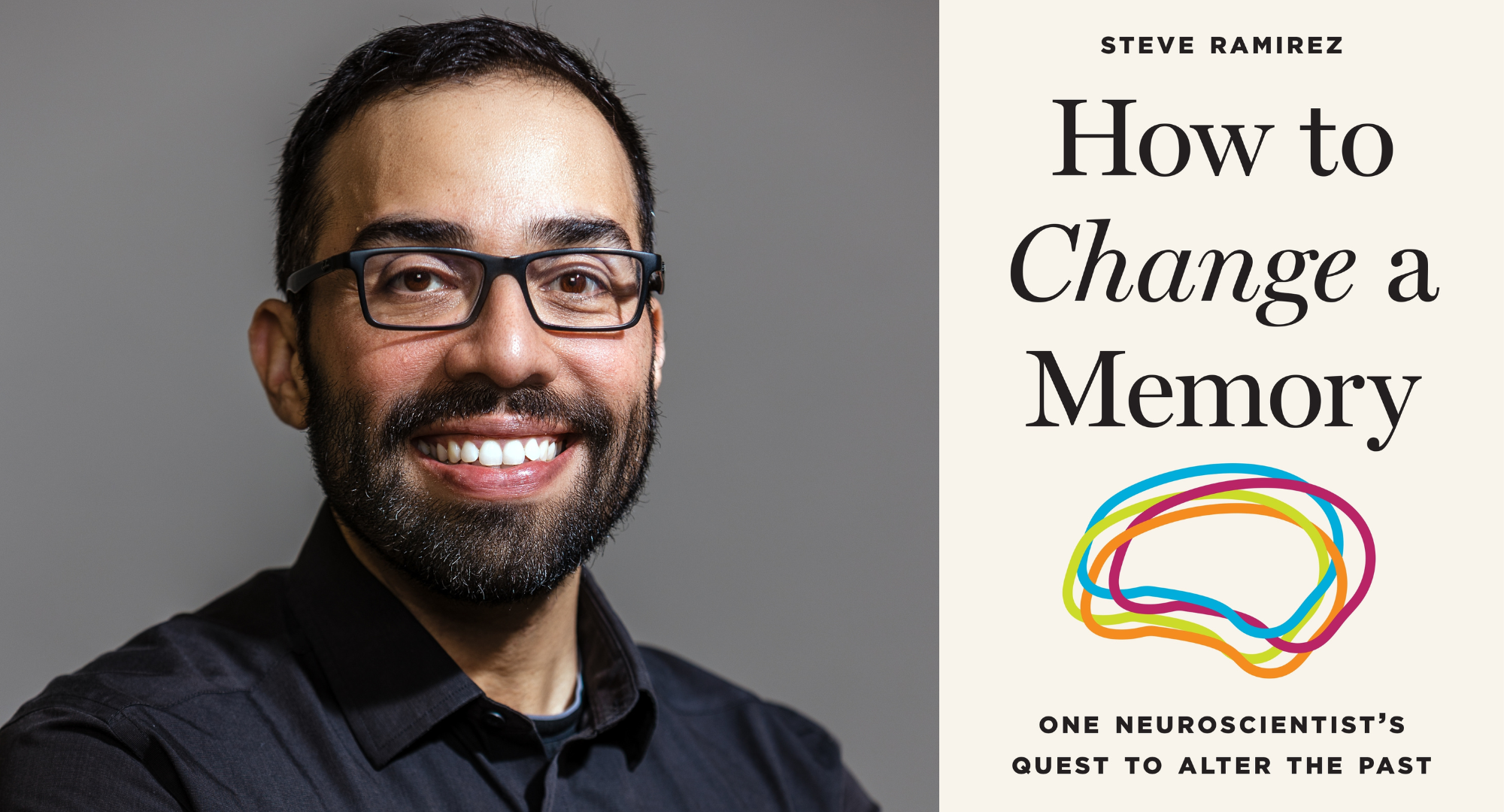

My guest, neuroscientist Steve Ramirez, has played a big role in moving forward memory manipulation in hopes of transforming the treatment of brain disorders. He’s written a book about it — and about the events in his life that caused him to think about changing his own memories. It’s called How to Change a Memory: One Neuroscientist’s Quest to Alter the Past. He joins me now. Welcome to Forum, Steve.

Steve Ramirez: Thank you so much for having me today.

Mina Kim: Really glad to have you. So where does the science of memory manipulation stand? Can you bring us up to speed generally on what scientists have successfully been able to do?

Steve Ramirez: Yeah. The short of it — and I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler — is that the answer to how to change a memory is to recall it. To remember the thing you’re trying to change.

One thing we’ve learned from decades of neuroscience research is that memory might feel like a video recording of the past that you can rewind again and again, but it’s much more dynamic — much more like a “Save As” file in a Word document. Memory is more flexible, changeable, dynamic than we expected, especially when we recall it. That’s when those changes begin to take place.

The point being: you can let change happen naturally, or you can have a goal — perhaps change that restores health or well-being to an individual.

Mina Kim: So to that end, you can do things like selectively target and erase specific memories?

Steve Ramirez: In mice, yes. In flies, in mice, in rats — some of our model organisms — it’s now possible to find the brain cells that hold an individual memory and tinker with those cells. We can stimulate them to activate the memory, or quiet them to quiet the memory so it won’t pop back up.

In humans, it’s much more difficult. We don’t know how to truly erase a memory in the human brain. But recalling one — that part is straightforward. I can say, “What did you have for dinner last night?” or “How was celebrating your last birthday?” and you’ll bring that memory online.

So it depends on the goal — whether it’s simply sharing a story, or actually trying to change the contents of a memory for therapeutic purposes. In mice, certainly possible. In humans, the psychology is trickier.

Mina Kim: And as you know very well, it’s very possible to implant memories in mice. Can you tell us how you’ve been able to artificially activate a memory and implant a new or false memory in them?

Steve Ramirez: Yeah, absolutely. I started as a graduate student at MIT in 2010, joining Susumu Tonegawa’s lab. The lab had this overarching mission: understand the science of how we learn and remember the past.

I teamed up with my late friend and day-to-day mentor, Xu Liu, who was designing the genetic engineering tools needed to find specific memories in the rodent brain. Xu and I teamed up quickly, with the collective goal of finding the cells that hold a memory and then tricking just those cells to turn on, to test if that was enough to activate the memory.

Xu had developed tools to find these cells, and we were shocked that the first big experiment we did — in 2011 — worked. The gist was that Xu had developed tools to find the brain cells holding a memory. First we tricked them to glow green so we could literally see them. Then we activated those glowing cells using optogenetics — “opto” meaning light, “genetics” meaning genetics — so we could make those cells activatable with lasers.

That was our million-dollar experiment. When we found the cells for one memory and used lasers to nudge them awake, the memory came back. It was the first demonstration of artificially activating a specific memory in the rodent brain. And since then, the last decade has been nothing short of a revolution — activating, changing, erasing, suppressing memories.

Mina Kim: And if I’m summarizing it correctly, basically: a mouse had a bad memory in one box. You put that mouse in a completely different box — no bad memories — and it’s happily scampering around. And then you activated the bad memory from the previous box, even though it hadn’t experienced it in the new one, and it froze in total fear?

Steve Ramirez: That’s exactly what we did. We started by inducing that freezing behavior — like if you heard a loud noise right now, you’d lock in place for a few seconds before fight-or-flight kicks in. It’s a behavioral measure that tells us whether the animal is recalling that negative experience.

In a safe environment, the mouse explores. But when we reactivate the negative memory, it stops and freezes for as long as we’re activating the cells. We wanted the most straightforward behavioral measure to test whether we were activating a memory — and once that worked, we could extend the work to more complex memories.

Mina Kim: Let me invite listeners into the conversation. What are your questions about the science of memory manipulation? And would you ever do it — erase, implant, or change a memory if you could? What hopes do you have for these kinds of tools? What concerns?

Stepping back a little bit, Steve, can you tell us how important our memories are to who we are and how we act? You’ve called memory nothing less than “the perpetual beating heart of life.”

Steve Ramirez: Yeah. To me, memory is simply what the brain does. And it’s amazing that no matter where you look in nature — algae, single-cell organisms, fruit flies, rodents, dogs, rabbits, humans — everywhere you see biology, you see memory. You see an organism soaking up experience, turning it into biologically meaningful change in the body and brain, and later accessing those changes to bring the memory back to life to make decisions.

For humans, memory is the thing that threads and unifies our overall sense of being — our identity. Who we are today is the sum total of the memories and experiences that have sculpted us up to this moment. Memory is the beating heart of life, and in its absence, those features of identity become dramatically impaired very quickly.

Mina Kim: Can I ask what it was like when you realized those initial mouse experiments worked — that you were able to activate a memory and essentially implant one in a mouse’s brain in a space it had never experienced?

Steve Ramirez: I was beside myself — but wildly nervous as a grad student. I relied on Xu to be my echo chamber, and I didn’t know how excited I should be. It was my first year at MIT, and I already had this doom-and-gloom feeling of, “What am I doing here? Someone in admissions must’ve made a mistake.” So when the experiments worked, I wanted to jump up and down because it was as black-and-white as an experiment could be.

But Xu was very laser-focused — didn’t really emote during experiments — just watching with razor-sharp focus. Afterwards I said, “That definitely just worked, right?” He confirmed it, and then immediately made a laundry list of follow-up experiments we needed to nail it down.

So inwardly I wanted to be over the moon, but I suppressed it because I didn’t know if it was appropriate to celebrate yet.

Mina Kim: That was very characteristic of Xu, wasn’t it?

Steve Ramirez: Oh yeah. I sometimes tend to say in a million words what I could say in a hundred. Xu was the opposite — every word had purpose. He thought before he spoke. I admired that, and I learned so much from that disciplined way of thinking. We were very complementary — a dynamic duo.

Mina Kim: We’re talking with neuroscientist Steve Ramirez, associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at Boston University. His new book is How to Change a Memory: One Neuroscientist’s Quest to Alter the Past.

We’ll have more with him — and you — after the break.