This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Mina Kim: Welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim. More than 230 environmental groups this month sent a letter to Congress warning that data centers — which power the internet and increasingly AI — are threatening Americans’ economic, climate, and water security.

Meanwhile, industry groups say the environmental impacts of data centers have been oversimplified and overblown. California is home to more than 320 data centers — the third most in the U.S. — with plans for more in the works.

So this hour, we take a closer look at how and why data centers can be so energy- and resource-intensive, and we’ll hear from you, listeners, on whether you think that tradeoff — delivering huge amounts of computing power — is worth it.

Joining me first is Molly Taft, senior climate reporter at Wired. Molly, welcome to Forum.

Molly Taft: Thank you so much for having me. I’m excited to talk about this.

Mina Kim: Good — because for people unfamiliar with these large warehouses full of servers called data centers, I think they’re wondering what you can tell us generally about what they’re like and what their resource needs are.

Molly Taft: Yeah. There’s been a lot of talk about them over the past few years as this buildout has exploded, but a lot of people don’t actually know what these centers need in terms of resources.

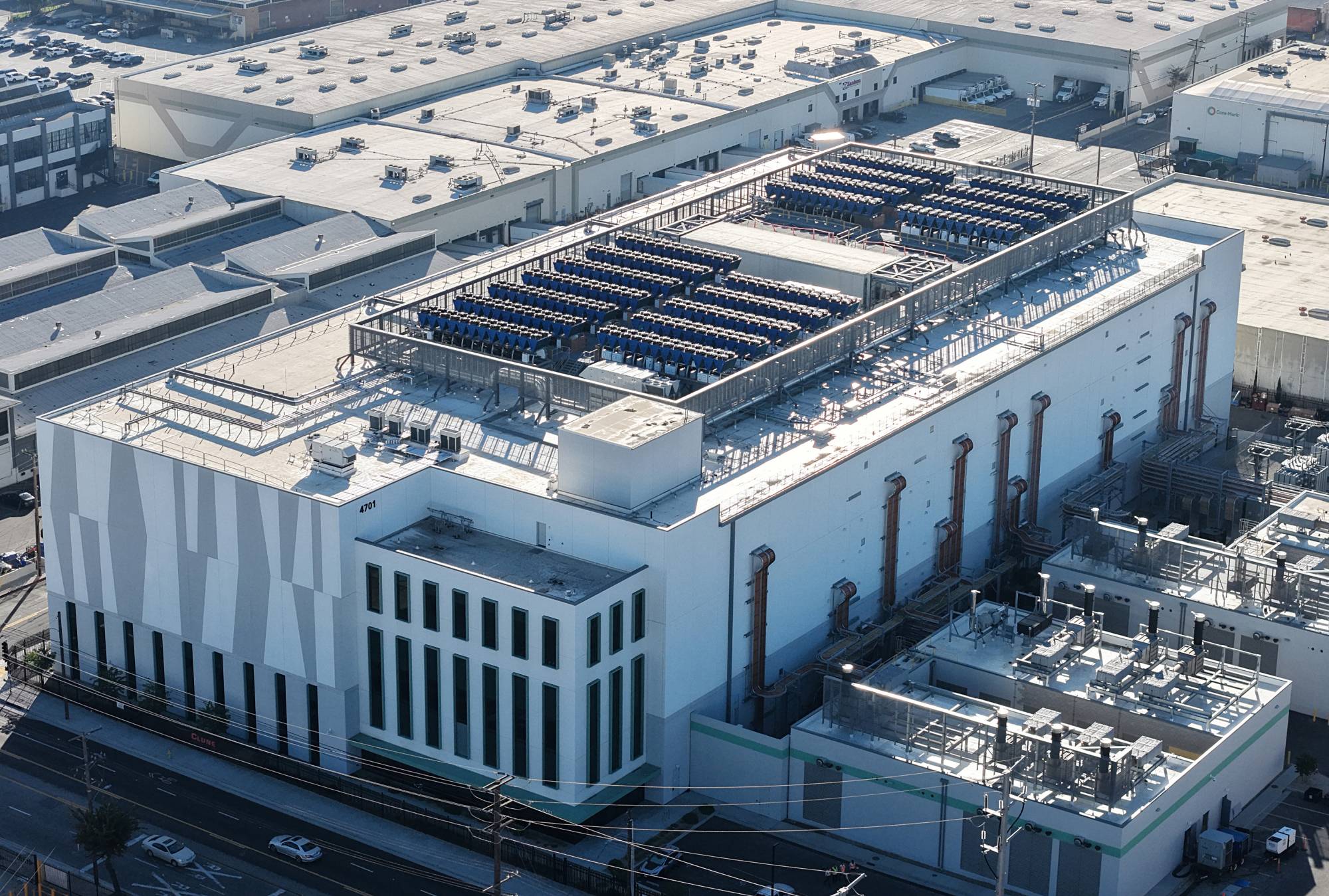

Very simply, a data center is a facility that houses a lot of servers that do computing tasks. This could be anything from hosting cloud files, to running programs that help you watch Netflix, to AI processes — which is really where the conversation has gone in the past few years.

Traditionally, many data centers built before 2022 or 2023 — in places like California and Virginia — were used for general computing processes like hosting websites or cloud services. But as AI has taken off, and as we are racing forward, the Trump administration has been very clear that it wants to develop AI capabilities as much as possible.

Especially after the advent of ChatGPT in November 2022, which really showed everyone what large language models can do, there began to be much more discussion about using space in these data centers to power AI.

This is a slightly different equation in terms of resources. These proposed data centers are much bigger, they use far more computing power than their predecessors, and as a result, they require a lot more electricity — and in some cases, a lot more water.

So when we talk about data centers right now, we have to divide between what’s existed over the past 10 or 15 years and what’s being proposed for the future. We’re really in an interesting middle ground.

Mina Kim: And I know this gets a little technical, but broadly speaking, why do AI models need so much energy to run?

Molly Taft: It’s a great question. Frankly, these models are doing far more than our past computing needs required. They’re crunching enormous amounts of information — especially during training. Training LLMs like ChatGPT requires a lot of energy.

These chips — you may have heard of NVIDIA chips — are extremely powerful. Servers use a tremendous amount of energy to do that work, and they also run hot. A lot of a data center’s electricity use actually goes toward cooling the servers to prevent overheating.

That’s where water sometimes comes in. Some data centers draw in water to cool the systems down. And when you add the scale of the data centers being proposed — especially hyperscalers from companies like Meta and Google — you’re talking about massive campuses with much larger physical footprints than we’ve seen before.

That raises serious questions about how much electricity we’ll need, and what resource use will look like over the next five to ten years.

Mina Kim: Right. And Molly, your recent piece focused specifically on how much water data centers use. What do they use the water for? Is it mainly cooling?

Molly Taft: Yes. Water is a really tricky issue, and it’s something a lot of people are concerned about.

When you see popular estimates floating around — like that ChatGPT uses a teaspoon of water per query, or that writing an email with an LLM is equivalent to a bottle of water — those figures usually combine different types of water use.

One is on-site water use. Data centers run hot, so some companies pipe in water that runs through the facility, then out to cooling towers, where some of it evaporates. That evaporated water is essentially lost to the atmosphere.

What makes this complicated is that water use is highly site-specific. You can design a data center that doesn’t use water, but that usually means using more electricity — which raises costs and carbon emissions, especially if the grid relies on fossil fuels.

On the other hand, companies may choose water-based cooling because it’s cheaper and lowers carbon emissions — but that can be problematic in places where water is scarce.

There are also experimental technologies using chemical coolants that could reduce both water and electricity use, but many of those involve “forever chemicals,” which raises environmental concerns. So there are a lot of tradeoffs for both companies and municipalities deciding whether to host data centers.

Mina Kim: And these data centers tend to use potable water, right?

Molly Taft: Yes. They technically could use salty or brackish water, but salt corrodes electronics. Potable water doesn’t necessarily mean drinking water — but it does need to be free of salt and certain minerals.

Some data centers draw fresh water from lakes or streams and pipe it back out, but many simply connect to municipal water supplies because it’s easier.

Mina Kim: You mentioned estimates from OpenAI suggesting a ChatGPT query uses about one-fifteenth of a teaspoon of water, while other estimates say it could be an entire bottle. That’s a huge range. Why is it so hard to know?

Molly Taft: It’s a great question, and that OpenAI figure really illustrates how little information we get from tech companies. Sam Altman mentioned that number offhand on his personal blog, which leaves many unanswered questions.

What does a single query mean? Does it include image or video generation? Does it account for stacked queries in AI-powered products? Does it include the cost of training the model, which often uses more energy and water than running queries on an existing model?

On the other end, some estimates include off-site water use — like the water used to generate electricity — which becomes incredibly complicated and varies widely by region.

A grid powered by solar in a dry region looks very different from one powered by hydropower. Data center design also varies. That’s why experts often say pulling out a single number isn’t very useful.

It’s also extremely difficult to get hard data. Water use is often proprietary. Communities may only learn what companies choose to disclose, and NDAs are common. California did pass a bill requiring more transparency, but Governor Newsom vetoed it in October.

So many estimates are based on incomplete information — making it a difficult guessing game.

Mina Kim: And as you noted, some in the industry argue the AI water issue is fake. Based on your reporting, is it dismissible?

Molly Taft: I don’t think it’s dismissible at all. Experts consistently say you can’t ignore it — especially when data centers are built in water-scarce regions, like parts of the Southwest.

That said, as an environmental reporter, I’m personally more concerned about electricity use than water use. The potential scale of energy demand is enormous — and that’s a much more pressing issue.

Mina Kim: And that’s exactly what we’ll get into after the break — the electricity issue. We’re talking with Molly Taft, senior climate reporter at Wired, about the environmental footprint of data centers.

We’ll be back with more after the break. I’m Mina Kim. This is Forum.