This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

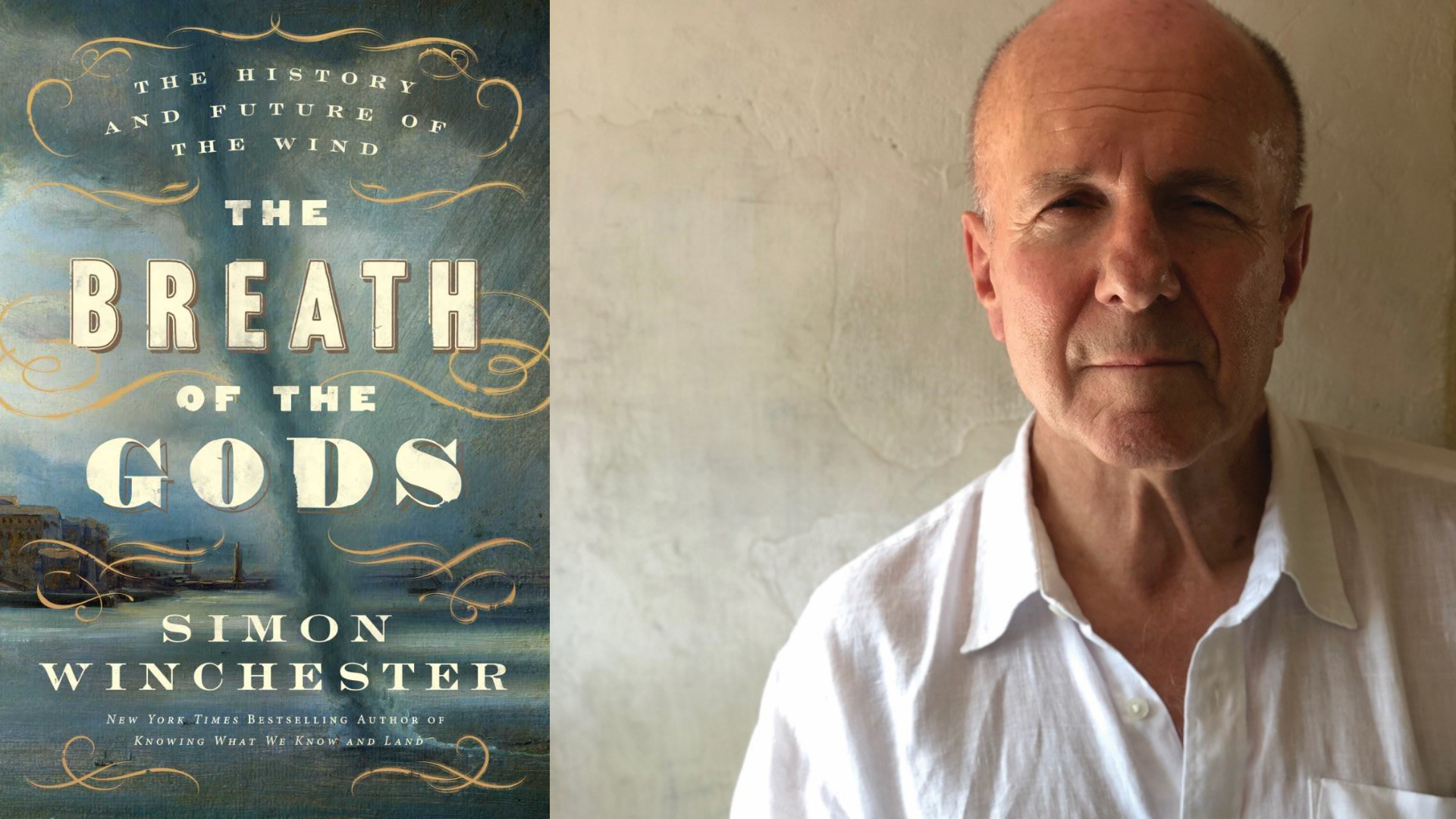

Mina Kim: Welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim. In his new book The Breath of the Gods: The History and Future of the Wind, journalist and author Simon Winchester writes: “Wind is a familiar thing, a thing whose very existence brings a kind of reassurance — yearned for when absent, delighting when gentle, accursed when either biting cold or parching hot, feared when violent, but familiar nonetheless — an ever-present reminder of the living presence of nature and of the planet that is so uniquely bathed in its presence.”

Listeners, when has the wind either scared or soothed you? Simon Winchester, welcome to Forum.

Simon Winchester: Well, thank you very much.

Mina Kim: Wind, as you say, is universal, constant, and influences the activity of just about every living thing. You call it an ever-present reminder of the living presence of nature. Is wind’s constancy part of what has captivated you so much about it?

Simon Winchester: I think so. I first experienced a period when there was no wind at all when I was sailing to the American base in Diego Garcia in the middle of the Indian Ocean. A friend and I had set off in a yacht from Cochin in South India, sailing down through Sri Lanka and the Maldives. And then suddenly the wind stopped.

The sea became like glass. The sails hung impotently from the masts. And that lasted for two weeks. It was searingly hot. Fish would come up, look around as if to say, “No, this is no good,” and go back down into the sea because the sea without wind — not moving at all — felt weirdly unnatural.

And that was, of course, the doldrums. This area around the equator takes its name from “doldrums,” meaning dull. It was deeply, deeply dull and felt so strange when there was no movement of air — not even the slightest breath.

So I think that first made me realize the wind is a delight. Of course, we hate it, as you mentioned, when it behaves badly. But we need it, we love it, and it’s essential.

Mina Kim: Another thing you talk about is the dual nature of wind — right? You’ve just described it to some degree: it can be violent or incredibly soothing; it can warm us or make us extremely cold; it can create things and destroy things. Help us appreciate this dual nature of wind the way you do.

Simon Winchester: Well, the British in particular love listening, as they go to sleep at night, to the shipping forecast at the end of the BBC broadcast day. I won’t get too technical, but all the sea areas around the British Isles have names familiar to us — Dogger, Thames, German Bight, Dover, and so on — and the weather forecasters give specific wind descriptions for each area as we’re nodding off.

It becomes almost poetic in the way they read it. You’re in bed with the rain lashing down against the windowpanes, pulling the covers closer to your chin, hearing about these poor mariners out near Iceland dealing with astonishing winds while you’re cozy and safe at home.

The British are attuned to this — enraptured by the fact that the British Isles, like most places in the world, are surrounded by winds of constant variation.

Mina Kim: You’re reminding me of all the words we have for wind — and that, as you discovered, the places with the most wind have the richest vocabularies. Can you talk about some of the ways we’ve tried to harness the wind linguistically?

Simon Winchester: To harness it? Well, Thor Heyerdahl, the great Pacific explorer, said quite sagely that man hoisted the first sail before he saddled the first horse.

The first written word denoting wind was in Sumerian — about four and a half thousand years BCE. Before that, it was simply described in conversation and associated with the gods. But once the Sumerians had writing, they named it “illi.”

It was denoted in cuneiform by three horizontal lines — a bit like the swoosh on a Nike running shoe. So the Mesopotamians were the first to record wind in written language.

You can imagine them trekking between the Tigris and Euphrates, coming to the great river, seeing a log floating by, and someone brave enough to sit astride it and be carried by the current — then adding a mast, then a sheepskin sail. Suddenly, by maneuvering that sail, you could determine the boat’s direction. That was the beginning of harnessing the wind.

From the feluccas on the Nile to Polynesian outriggers — which prevent capsizing when wind heaves the boat over — to the great square-riggers of later centuries, wind allowed us to travel vast distances until the age of sail ended in the 19th century with the invention of the steam engine.

So from the very beginning — four and a half thousand years BCE — wind was used to travel. It did many other things, of course, but that was the first.

Mina Kim: Let me bring listeners into the conversation. Listeners, does your work or play rely on the wind? When do you really notice it? Have the Diablo winds or Santa Ana winds shaped your experience of living in California? When has the wind scared or soothed you?

You can email us at forum@kqed.org; find us on Discord, Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, or Threads @kqedforum; or call us at 866-733-6786.

We’re talking with Simon Winchester, journalist and author of The Breath of the Gods: The History and Future of the Wind.

And Simon, I want to ask you about a major historical event that was essentially exposed because of the wind — the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Simon Winchester: I remember this only too well. I was living in Oxford at the time, in the kitchen making a cup of coffee, when the BBC — which seldom breaks into its afternoon broadcasts — announced that authorities in Sweden had detected a plume of radiation whose signature suggested a nuclear catastrophe somewhere.

It had been detected north of Stockholm. Where had it come from? The winds that day — April 1986 — were blowing into Sweden from the southeast. They had carried a plume of radiation across the Baltic, across Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, across the Iron Curtain, to the western USSR — specifically Ukraine — and more specifically to a power station near the town of Pripyat: Chernobyl.

Moscow said nothing. “Nothing to see here.” But the wind revealed the truth. The plume shifted slightly and blew dangerous radiation across Germany, Poland, northern France, even the United Kingdom, where people were told not to drink milk and to take precautions.

Eventually, the Soviets admitted something had happened — and that they needed help.

Here’s the extraordinary part: normally, the wind over Ukraine in April blows from the west. Had that been the case, the radiation plume would have blown over the Urals, across Siberia, into Kazakhstan — and no one outside the Soviet Union would have known anything had happened.

Gorbachev later said the collapse of the Soviet Union was triggered by the Chernobyl explosion. And weirdly, the only reason the world knew about it was because of a fickle wind.

Mina Kim: Wow. You warn us that understanding the mechanics of wind is daunting, but remind us generally what causes wind and what its main attributes are.

Simon Winchester: Well, the person who really captured it was Aristotle — the cleverest person of all time, I think. Writing around 300 BCE, he said wind is caused by heating of the atmosphere, which makes air rise, and then cooler surrounding air rushes in to fill the void.

That movement of air — and that’s how the OED defines wind — is wind. It’s as simple as that: an atmosphere and a source of heat. Aristotle nailed it.

It’s become more mathematical since, but the essence is the same: air moving upward, the gap filled by air moving horizontally. That is wind.

Mina Kim: And all wind has speed, direction, pressure, and force.

Simon Winchester: Except on the top of Mount Washington in New Hampshire. I went there for my 80th birthday — the windiest place in the world, with a recorded wind speed of 231 miles an hour. One Australian station has exceeded that in recent years.

But on that particular day — my birthday — there was no wind at all. The meters were flat, like a speedometer on a parked car. I said, “What’s going on?” And the observers — there are always two up there — looked sheepish. The windiest place in the world had no wind that day.

Mina Kim: After the break, I want to get into that. Is this a one-off or does it mark something bigger? We’ll talk about it right after the break.

Listeners, we’re talking with Simon Winchester about his new book The Breath of the Gods: The History and Future of the Wind. We’ll take your calls and questions. Stay with us.

This is Forum. I’m Mina Kim.