This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Mina Kim: Welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim.

A German general is warning of Russian attacks on NATO countries and says a deterrence plan is urgent. Recent reports of increased drone incursions and sabotage of undersea cables suggest a surge in Russia’s efforts to probe NATO defenses.

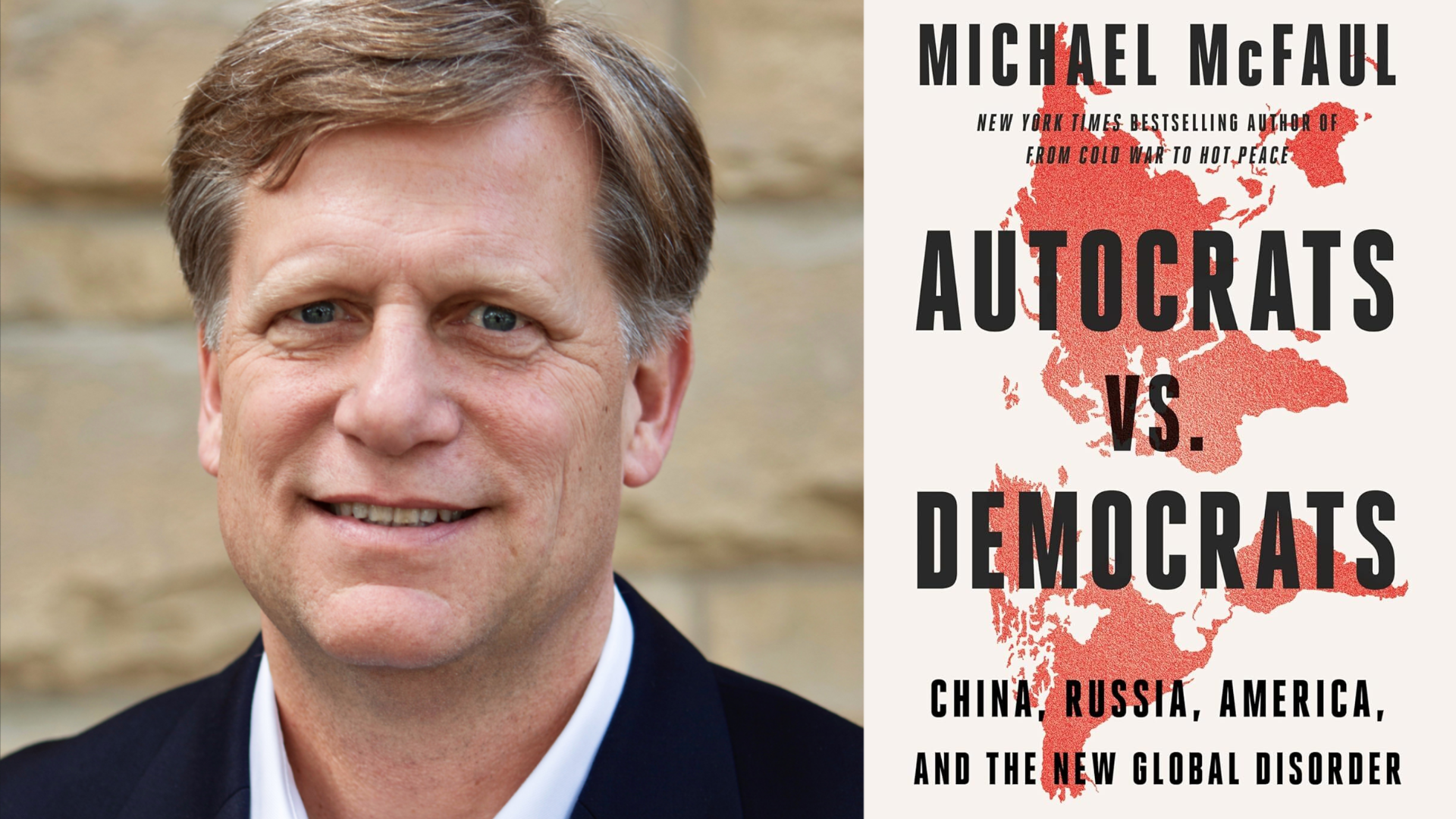

Michael McFaul, former U.S. ambassador to Russia, says the country’s willingness to deploy military power makes it a real threat to the U.S. And as he writes in his new book, Autocrats versus Democrats, relations between the two countries have never been as confrontational and dangerous as they are today. Ambassador McFaul, welcome back to Forum.

Michael McFaul: Thanks for having me.

Mina Kim: I do want to start by looking at the state of play between Russia and the U.S. First — why do you say relations have never been more dangerous?

Michael McFaul: Well, they were more dangerous in the early Soviet period — so if you go way back decades ago, that’s true. But in post-Soviet Russia, this is the most dangerous time, for the simple fact that Putin has erected a dictatorship at home.

I think it’s actually more autocratic today in Putin’s Russia than it was in the late Soviet period under Gorbachev. But now he’s in a mood of imperial conquest. It started in Georgia in 2008, then he invaded Ukraine in 2014 for the first time, helped prop up Assad in 2015 for several years, and then in 2022 launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine that continues to this day.

As he’s done that — the first conventional war in Europe since World War II — he’s also, just as you said, probing how the alliance holds. He’s testing the NATO alliance, and that worries me because that could drag us into a direct conflict with Russia.

Mina Kim: Yeah. Even as he’s bogged down in this full-scale invasion of Ukraine, you’re not seeing that as something that would deter him from going further with regard to deploying military power.

Michael McFaul: Well, I hope it does — I want to be clear about that. And I think we should be taking preventive measures to enhance deterrence and reduce the probability of an attack on an allied NATO country.

But what I also see with Vladimir Putin — and I’ve followed his career for a long time; I met him in 1991 and dealt with him for five years when I worked in the Obama administration — is that he’s become increasingly motivated by ideas. He’s an ideological leader. He’s increasingly less rational, in my view, about advancing Russia’s security or economic interests — and that makes him very dangerous.

Mina Kim: Can you say a little more about that? Help us understand the ideological drive — why he’s so intent on, you know, basically conquering Ukraine?

Michael McFaul: Well, he wasn’t always that way, at least in my read of him. He was an accidental president back in 2000. There was no popular demand for Putin or “Putinism.” He wants everyone to forget that he actually worked in the Kremlin with Boris Yeltsin.

He was not an anti-systemic guy — he was a systemic guy then. He was pretty pro-market back then, and pretty pro-West. Again, he wants everyone to forget that he once suggested Russia should join NATO.

He was never democratic — he shut down democratic institutions right away — but over time, he’s become more and more threatened by democratic ideas. When Ukrainians rose up during the Orange Revolution in 2004, that was a threat to his own arguments for autocratic rule inside Russia. Then the Arab Spring happened in 2011, and I heard him speak about that — he viewed it as the U.S. undermining autocrats.

And then that same year, a similar phenomenon happened inside Russia. There was a parliamentary vote — stolen, though by what I’d call “normal levels” of falsification. I remember sitting in the White House Situation Room saying, “This is just a normal Russian election — six, seven percent — no big deal.”

But in December 2011, there were lots of Russians — middle-class people, people with property — who didn’t want their votes stolen. They even used a phrase Americans will remember: “No taxation without representation.”

First 500, then 5,000, then 50,000, then 200,000 people came to the streets of Moscow demanding free and fair elections. And for Vladimir Putin, he saw the hand of President Obama and Secretary Clinton.

When I arrived in 2012, just a few weeks after those demonstrations started, he accused us of fomenting revolution against him — and that’s what he fears. He fears people organizing for democratic systems of government, and he associates that with the West. And partly, he’s right about that — not all presidents, but most have supported democracy, freedom, and liberty. That threatens Putin’s autocratic regime.

Mina Kim: You’ve also mentioned your concern that Europe could get pulled into a ground war — and along with it, the U.S. as well. Even though the overall balance of power in Europe favors NATO, why would Putin attack? What would be his goal — say, on a smaller scale, in a country along the Baltic coastline?

Michael McFaul: He wants to foment division within the NATO alliance. He wants to test it. So let’s say he goes into Estonia — there’s a city called Narva on the border, a Russian-speaking place.

Let’s say there’s some altercation there between Russian speakers and Estonian speakers, and someone gets killed. Then he sends in his special forces — they kill a bunch of Estonians and then leave. That’s an attack on a NATO country.

But what he’s gambling on is that when NATO meets, the alliance won’t say “an attack on one is an attack on all,” and won’t go to war with Russia. That sows division within NATO — and that’s what he wants. He wants to see the dissolution of the alliance.

Mina Kim: Do you worry about whether the U.S. will come to the aid of a NATO country?

Michael McFaul: Yes, of course. Especially under President Trump. And I’m not the only one worried. I can tell you, there are leaders in those countries who are worried we are no longer credibly committed to the NATO alliance — and it’s not just Europe. Countries in Asia allied with the U.S. are worried too.

Mina Kim: Let me invite listeners into the conversation. What questions do you have about Russia’s actions against allies and partners in Europe — and broadly for Michael McFaul, professor of political science and director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford, and as I mentioned earlier, former U.S. ambassador to Russia?

He’s written a new book called Autocrats versus Democrats. 866-733-6786 is the number. The email address is forum@kqed.org. Find us on Discord, Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, or Threads at @kqedforum.

I also want to talk to you about the state of play with regard to Russia’s war in Ukraine — and how you assess its trajectory right now.

Michael McFaul: It’s such a tragic war — such a horrific, barbaric war. I talk to Ukrainians every day — I’ve talked to half a dozen already this morning.

On the one hand, Ukrainian warriors and the people who support them have heroically defended their country and stopped the invasion by what was, at the time, the third most powerful army in the world. If the war ends soon, that’s how it’ll be remembered in Ukrainian history books — they repelled the Russians.

But in the short term, the tragic reality is that Putin doesn’t care how many Russian soldiers — young boys — he sends to their deaths every day to take tiny bits of Ukrainian territory. Day by day, week by week, month by month — very small pieces of land, but they’re taking more.

That’s a challenge for Ukraine. They’re running out of soldiers, weapons, money — and they’re worried the West won’t help them stop the Russian advance. It’s a pretty dire situation on the front line right now.

Mina Kim: Yeah. Though at the same time, Russia has suffered such significant casualties. At what point is that something the people of Russia won’t stand for anymore?

Michael McFaul: Well, I’d hope it would’ve already happened. But it’s a strong dictatorship inside Putin’s Russia. You can go to jail for eight years for criticizing the war. He killed Alexei Navalny last year — the most outspoken opponent of the war and leader of the democratic opposition.

So it’s very costly to protest inside Russia today. I also want to underscore that we don’t have good polling data in Russia — so I want to be careful — but there are millions of Russians who support this war because they believe Putin’s propaganda. They believe NATO is out to destroy Russia and that this is a defensive war to stop NATO expansion.

Tragically, twenty-six years of propaganda have changed the views of many Russians inside Russia.

Mina Kim: Late last month, the Trump administration sanctioned two major Russian oil companies. Do you think this will have any material effect on Russia’s war?

Michael McFaul: Yes. I think finally, President Trump has implemented new sanctions — the first since returning to the White House.

It’s hard to measure the short-term impact of sanctions. Everyone thinks they’re a magic wand — you just put sanctions in place and Putin stops. It doesn’t work that way. They still have lots of resources and lots of ways to sell their natural resources to underwrite their war machine.

They still have China buying oil and gas and providing technological components to support them. They still have North Korea providing soldiers and Iran providing drones. The autocrats are united in helping their autocratic ally, Vladimir Putin.

But increasing sanctions makes it harder for Putin to conduct the war. He’s going to have less money as a result. And I’d like to see a new set of sanctions every week.

I think about it like parking tickets here at Stanford — you park your car in the wrong place, you get a ticket that first day. But if your car’s still there the next day, you get another ticket. That’s how sanctions should work — they should ratchet up every single day.

Mina Kim: We’re talking with Michael McFaul about the external threats facing American democracy — including Russia — and the efforts it’s making right now to challenge the global order.

He’s written a new book called Autocrats versus Democrats: China, Russia, America, and the New Global Disorder. We’ll have more with him — and with you — after the break. I’m Mina Kim.