This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Mina Kim: Welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim.

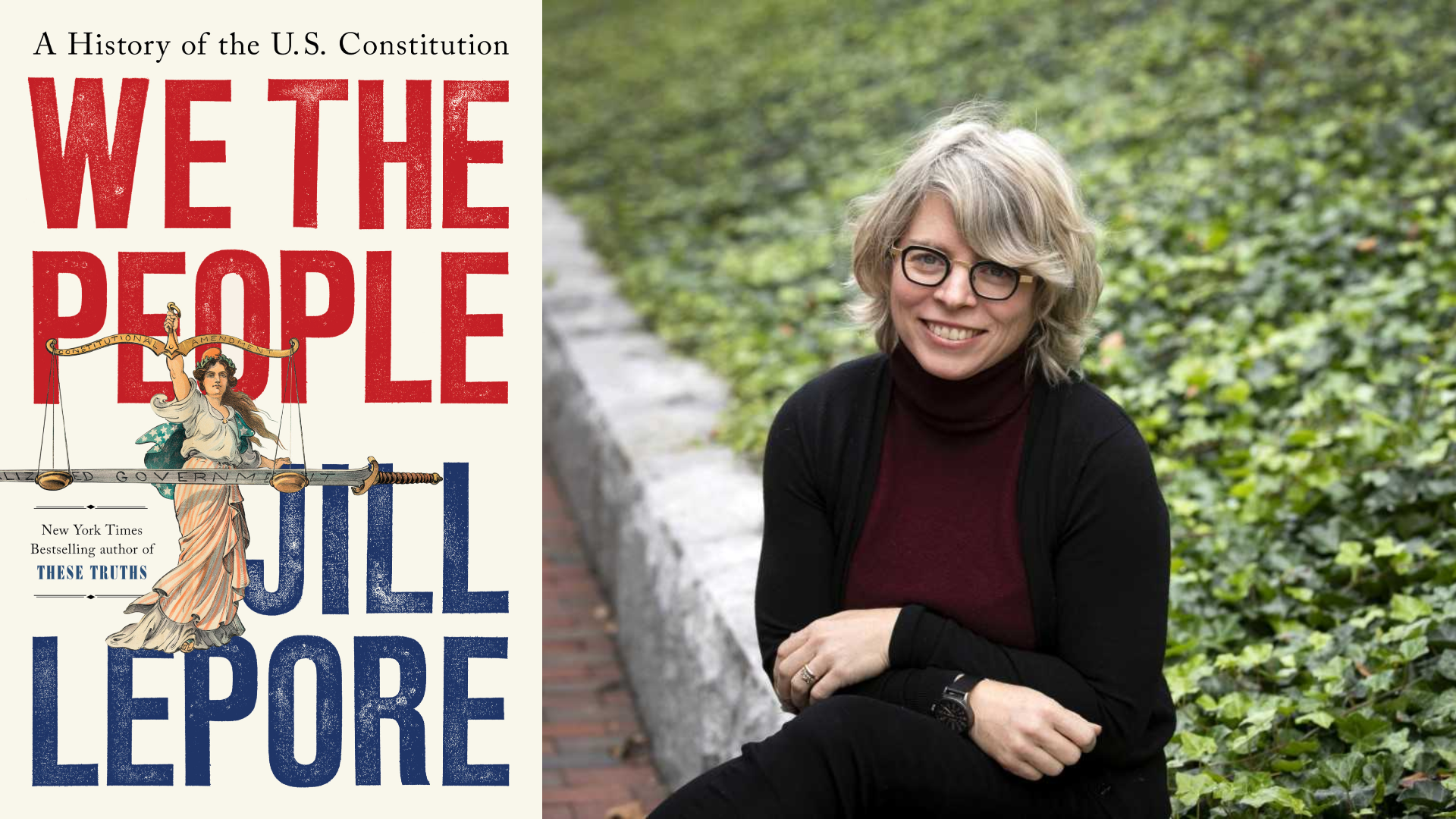

In her new history of the U.S. Constitution, Harvard historian and New Yorker staff writer Jill Lepore quotes Thomas Jefferson in 1816, lamenting how some men look at constitutions with “sanctimonious reverence” and deem them like the Ark of the Covenant — too sacred to be touched. But the Constitution, Lepore says, was intended to be amended. That was a founding principle — and yet, we’ve all but abandoned the practice.

That’s had profound consequences, including leaving us with what Lepore calls “aristocratic provisions,” like the Electoral College and life tenure for Supreme Court justices.

Listeners, how would you amend the Constitution if you could? Tell us by calling 866-733-6786, emailing forum@kqed.org, or posting on our social channels @kqedforum. Jill Lepore’s new book is called We the People. Welcome to Forum, Jill.

Jill Lepore: Thanks so much for having me.

Mina Kim: So, talk about why amendment is so core to the U.S. Constitution.

Jill Lepore: The U.S. Constitution — and the state constitutions that preceded it — were ingenious late-18th-century inventions. It was a new thing at the time to write down a constitution.

England’s constitution, of course, is unwritten — it remains unwritten today. So it was a founding principle of independence that these new states, and the new government that united them, would have written constitutions for the sake of transparency. People could look at the Constitution and see: the government has this power but not that power; I have these rights.

That was important, but it also created a problem. If you’re going to write down a constitution, you need some mechanism to alter it — because change will be necessary. An unwritten constitution can evolve quietly through practice and custom, but a written one risks becoming fixed and brittle.

So the mechanism early Americans came up with was an amendment provision — first appearing in state constitutions, and then included in the U.S. Constitution in 1787.

Mina Kim: They ingeniously accounted for the need for change — but it’s hard to pass a constitutional amendment. Can you remind us what the process is?

Jill Lepore: It’s worth revisiting, because a lot of Americans don’t realize the Constitution can be amended — it happens so infrequently and hasn’t happened in so long. It’s difficult — essentially impossible now — but that wasn’t always the case.

Article V lays out the methods. One way: someone in Congress introduces an amendment. If it passes both houses by a two-thirds supermajority, it goes to the states for ratification. The states can ratify through their legislatures or by holding state conventions. If three-quarters of the states ratify, the amendment becomes part of the Constitution.

There’s also an alternate method: if enough states petition Congress, they can call their own convention to introduce amendments.

Mina Kim: And I imagine that didn’t sound so complicated in the 1780s, when there were just thirteen colonies and no political parties.

Jill Lepore: Right — it was complicated, but they didn’t want to make it too easy. Like other supermajority requirements — treaties needing two-thirds Senate approval, or two-thirds for impeachment — it was meant to be difficult but doable.

Before the U.S. Constitution, the states were bound under the Articles of Confederation, which required unanimous consent from all thirteen states for any amendment. That never happened. So two-thirds felt easier than unanimity — they thought they were simplifying. They just didn’t foresee political parties emerging to make consensus far harder.

Mina Kim: And the effect has been that it’s only been amended twenty-seven times since ratification in 1788. You write that the last meaningful one was the 26th Amendment. What did that do, and why did it work?

Jill Lepore: Amendments have tended to come in clusters — like getting three wishes when you rub the lamp. There were the first ten, the Bill of Rights; then the Civil War and Reconstruction Amendments — the 13th, 14th, and 15th; four Progressive Era amendments; and four between 1961 and 1971.

The last of those, in 1971, was the 26th Amendment, which lowered the voting age from 21 to 18 — something long debated. It finally passed because of the Vietnam War, when 18-year-olds were being drafted to fight but couldn’t vote. It was a direct response to the antiwar movement.

Mina Kim: So, just twenty-seven amendments in total — compared to what? How often are state constitutions amended? I read that California’s has been changed nearly 500 times.

Jill Lepore: That’s right. And the number of proposed amendments is staggering. There have been roughly twelve thousand proposed amendments to the U.S. Constitution in Congress — only twenty-seven ratified.

At the state level, though, about twelve thousand constitutional amendments have been proposed, and around eight thousand ratified — a seventy-five percent success rate. That’s typical around the world.

Most national constitutions are easier to amend — and don’t even last very long. The average written constitution lasts around nineteen years before it’s replaced or rewritten. Nation-states often hold constitutional conventions to start fresh. U.S. states used to do that, too — they’ve held more than 250 conventions.

Now, that’s not to say more amendments are always better. Some states, like California, amend too frequently. Their constitutions can start to resemble policy manuals rather than governing charters. Constitutions are meant to govern the government; laws govern the people. When you over-amend, that distinction collapses.

Mina Kim: Yeah — as you say, the right rate is one thing. But you also argue there are consequences when a nation’s constitution is too difficult to amend. What are some of those?

Jill Lepore: James Madison — often called the “father of the Constitution” — feared that as constitutions age, they become objects of veneration. Jefferson feared this too. As the founders die off, the document takes on a kind of majesty or mystique that can harden it.

Some Americans think that’s good — that our Constitution’s stability is its strength. But the counterargument is that a constitution’s legitimacy depends on the people’s ability to amend it. If we lose that capacity — in practice or imagination — because of polarization or government dysfunction, then the legitimacy of the Constitution itself begins to wobble. That’s dangerous.

Mina Kim: You say that can even lead to political violence — and overreach.

Jill Lepore: Right. The framers themselves described amendment as a safety valve. After drafting the Constitution in secret in Philadelphia, they had to convince the states to ratify it — not an easy sell.

The Constitution granted much more power to the federal government than the Articles of Confederation had, even with checks and balances. So one way they sold it was by saying: “Don’t worry — you can amend it. If you don’t like it, you can change it.”

Some states wanted to amend it before ratifying, proposing more than 200 amendments. The Federalists said, “Please ratify it first — we promise we’ll amend it once the first Congress meets.” And they did — that’s how we got the Bill of Rights.

They believed amendment would be what made this government uniquely flexible — that “the people” would always have the power to make fundamental changes if needed, whether to add term limits or even abolish the presidency.

Mina Kim: Hold that thought, Jill. More after the break. I’m Mina Kim.