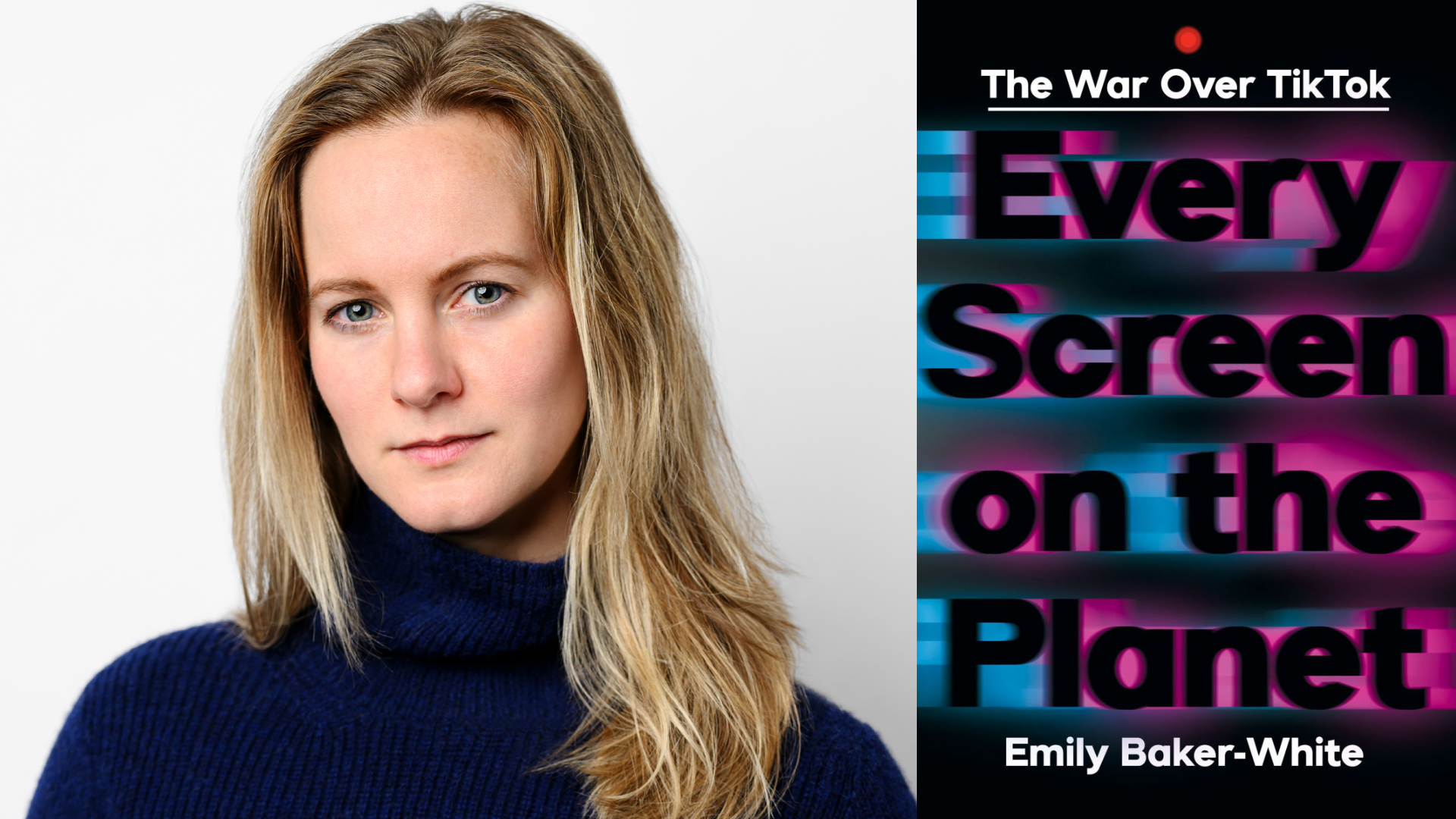

A group of American investors, including Silicon Valley allies of President Trump, is expected to take control of TikTok’s U.S. operations from Chinese parent company ByteDance, according to the White House. The video sharing platform has come under heavy bipartisan criticism as a national security risk. We’ll talk to Forbes investigative reporter Emily Baker-White about the proposed deal and what it could mean for TikTok’s millions of users. Baker-White’s new book is “Every Screen On The Planet: The War Over TikTok.”

Emily Baker-White on ‘The War Over TikTok’

Guests:

Emily Baker-White, investigative reporter and senior writer, Forbes

This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Mina Kim: From KQED, welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim.

If you need a TikTok refresher: it’s the addictive video-sharing platform powered by an algorithm that predicts and auto-feeds the next clip you’ll want to see based on the ones you’ve just lingered on. As Forbes investigative reporter Emily Baker-White tells us, TikTok became more visited than Google in 2021 and amassed more than a billion global users by 2024.

Now, the White House says a group of American investors — and allies of the president — will take control of TikTok’s U.S. operations from its Chinese parent company. For more on what we know about the deal so far, I’m joined by Emily Baker-White, whose new book is “Every Screen on the Planet: The War Over TikTok.” Emily, welcome to Forum.

Emily Baker-White: Thanks so much for having me.

Mina Kim: So what do you think made TikTok so wildly popular here? Last I looked, there were more than 170 million users in the U.S.

Emily Baker-White: Yeah. When I think about what makes TikTok different from other apps — when you join Facebook, you friend a bunch of people, you follow accounts. Same thing on Instagram. When you go to YouTube, you search for things. On TikTok, you just open the app — and it goes.

TikTok is this thing that happens to you. And as a result, it relies much more heavily on your revealed preferences than your stated preferences. On Facebook or YouTube, you tell the platform what you want to see, and it gives that back to you. But on TikTok, it’s inferring what you want to see without your explicit signals — relying instead on the ones you give unintentionally.

And as you said in the intro, it’s all about where you linger. You may linger on things you don’t actually want to see more of — content about divorce or alcoholism, for example — but the app infers that you’re interested because you paused a little longer. That’s why TikTok feels so addictive.

That’s why people say, “it knew I was pregnant before I was pregnant,” “it knew I was gay before I knew I was gay.” Those are very subtle signals you’re giving off — not likes or shares, but micro-behaviors the app can still read and respond to.

Mina Kim: And its recommendations — at least most of them — seem to be working pretty well, given its user base. So remind us why Trump, in his first term, and then Biden and Congress were so intent on controlling or even banning TikTok.

Emily Baker-White: People on both sides of the political spectrum have worried for years that TikTok is hugely powerful. It shapes what information we consume and knows an enormous amount about us.

TikTok is owned by a Chinese parent company, ByteDance — basically the Google of China. It’s a massive, powerful firm, and all Chinese companies have to contend with the fact that their government can demand anything of them at any moment. They have no real way to say no.

So U.S. regulators and national-security experts feared that the Chinese government could, in theory, walk into ByteDance, threaten an engineer, and demand access to data — and that engineer would have no recourse. There’s no due process in China. So the thinking in Washington was: if all this data is accessible in China, and if the power to shape what Americans see lies there too, that’s a national-security risk. We either need ByteDance to change its structure — or we need to ban TikTok in the U.S.

Mina Kim: Because they could collect your data, maybe spy on you, even send propaganda?

Emily Baker-White: Yeah, those are the concerns.

Mina Kim: You’ve also written about worries that the Chinese government could use people’s old posts against them later in life.

Emily Baker-White: Absolutely. When people hear “surveillance,” some say, “I don’t care if Beijing sees my dance moves.” Fair enough. But TikTok and ByteDance don’t just collect dance moves — they collect what you linger on, what you like, what interests you most.

So national-security experts worry that someone who shrugs that off today could, ten years from now, be a U.S. service member, a congressional staffer, or an intelligence worker. And if that person’s decade-old TikTok data is still accessible, a foreign adversary could use it for blackmail or extortion.

Mina Kim: Congress responded in April 2024 with a law called the “Protecting Americans from Foreign Adversary-Controlled Applications Act.” Courts upheld it — but Trump, in his second term, has delayed enforcing it. So take us to the present day.

Emily Baker-White: Right. This is the law that Congress passed and President Biden signed last year. It said ByteDance had to sell off TikTok’s U.S. operations — or the app would be banned here. The idea was to sever Chinese influence: TikTok could continue only if independent of ByteDance.

Here’s what happened: The deadline for ByteDance to sell TikTok was the day before Inauguration Day. Trump was reelected, and on the eve of his inauguration, he said to American companies that work with TikTok — Apple, Google, Oracle — “don’t take it down, don’t turn TikTok off.”

At that moment, he had no official power. He was a private citizen saying: “Disobey this law. Come with me — the guy who tomorrow will have a lot of power.” And those companies did it. They brought TikTok back online after just a few hours — in violation of clear U.S. law.

Once in office, Trump used the discretion presidents have in enforcing laws. He said, essentially: “Yes, this is the law. But I’m not going to enforce it. We’ll keep TikTok online while I negotiate a sale.”

Mina Kim: That’s right — he’s calling himself “TikTok Saver.” He even issued an executive order last month outlining a plan for U.S. investors to take control of TikTok’s U.S. operations. But you’ve raised questions about that plan — about how much control and influence China might still retain.

Emily Baker-White: There’s a lot we don’t know about this deal, but here’s what’s been reported.

Reuters said a new group of American investors would take control of TikTok’s U.S. data operations — but ByteDance would continue to control advertising and e-commerce. Bloomberg reported that ByteDance would be entitled to roughly 50% of U.S. TikTok’s revenue through a licensing agreement. Under that agreement, ByteDance would keep the “For You” algorithm — the sticky predictive machine that powers TikTok — and license it to the U.S. group, which would then send a share of profits back to ByteDance.

Mina Kim: So why is ByteDance keeping control of advertising and e-commerce concerning?

Emily Baker-White: You can run influence operations through advertising. I’m not saying this deal would enable that — we don’t know enough to say — but the public deserves clarity on who controls what.

If we’re talking about a deal with national-security implications, and Congress clearly intended a complete severing between TikTok and ByteDance, the fact that that doesn’t appear to be happening is important. We need to know who decides which ads can appear on U.S. TikTok.

We already know the Chinese government has placed propagandizing ads on TikTok in Europe — where disclosure laws make that visible. The U.S. doesn’t have those laws. So we don’t know if similar ads have run here.

Mina Kim: And what about concerns over control of the algorithm itself?

Emily Baker-White: There are many kinds of software licenses. We know ByteDance will license the algorithm to the new U.S. TikTok group, but we don’t know what kind of license it is.

Some licenses give you a clean copy of the code — you can modify it however you want. Others restrict what you can change and require the licensor to push updates. If it’s that kind of deal, ByteDance could still exert influence through ongoing control of the code.

The truth is, nobody has released the agreement. So we can’t assess whether this really cuts off Chinese control or not.

Mina Kim: So you’re saying this hasn’t fully lifted your concerns about data collection, surveillance, or content moderation.

Emily Baker-White: Right. I think some lawmakers are asking: “Isn’t some separation better than none?” And probably yes — it sounds like data will be more separated from ByteDance under this deal. Which data, and how much more, we don’t know.

Does it alleviate my concerns? Not until I’ve seen the deal. But is it better than nothing? Probably, yes.

Mina Kim: And we may not see the deal until “it’s too late.”

Emily Baker-White: Yep. That’s true. If you have a copy of this deal, you can reach me on Signal. Always worth a try.

Mina Kim: We’re talking with Forbes investigative reporter Emily Baker-White, whose new book is “Every Screen on the Planet: The War Over TikTok.” We’re getting her thoughts on the TikTok deal — what we know, and what we don’t. More after the break. I’m Mina Kim.