This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Mina Kim: From KQED, welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim. When you think of a charlatan, who comes to mind? People out to exploit you with their promises are nothing new. But according to my guest, Francisco “Quico” Toro, spotting the charlatan has become a key survival skill for the twenty-first century, when technology has improved the charlatan’s methods and created an endless number of potential marks.

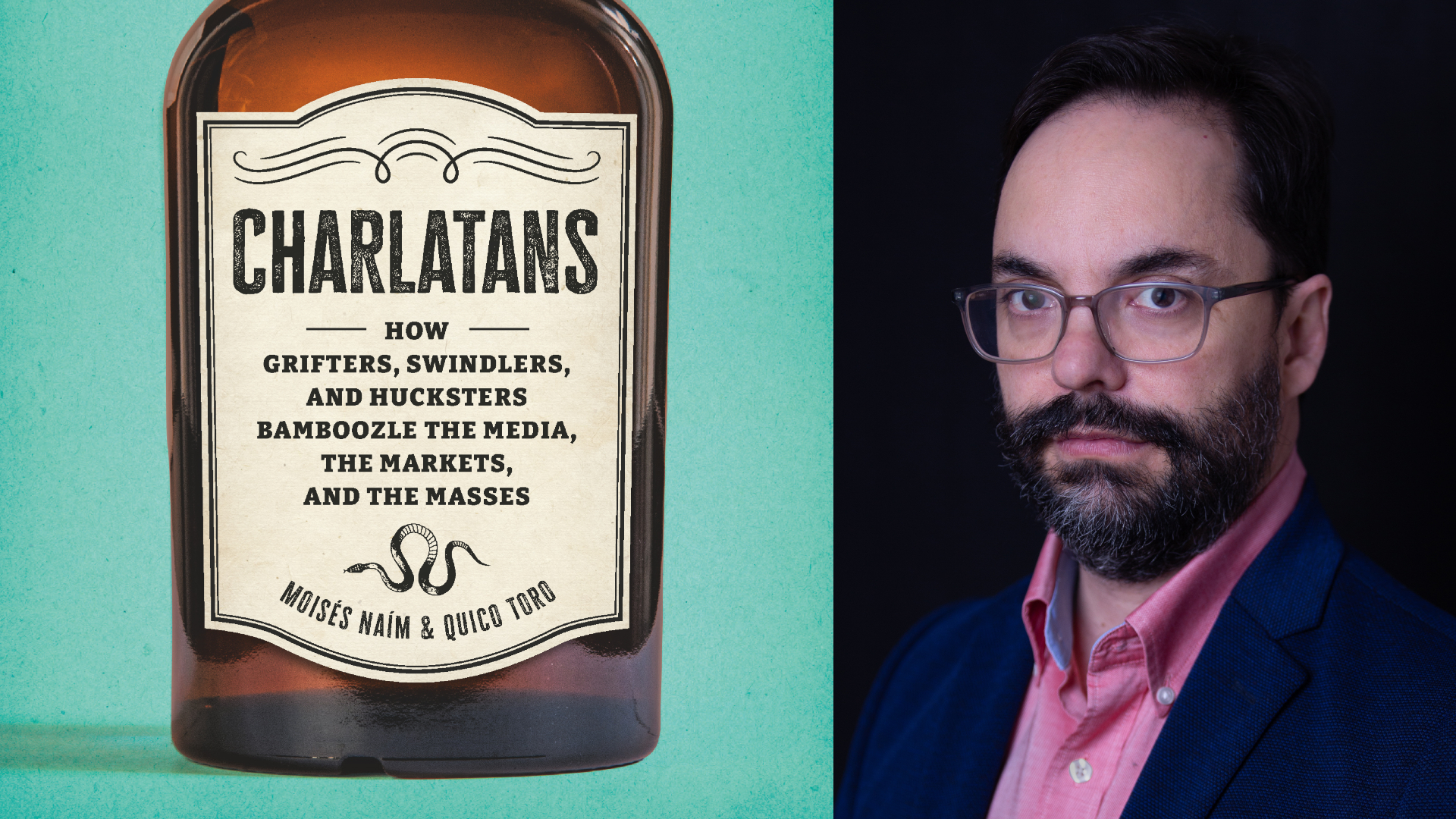

Have you or someone close to you ever been influenced by someone you later realized was a charlatan? Toro has co-written, with Moisés Naím, a new book out today called Charlatans: How Grifters, Swindlers, and Hucksters Bamboozle the Media, the Markets, and the Masses. He joins me now. Welcome to Forum, Quico.

Francisco “Quico” Toro: Thanks so much for having me.

Mina Kim: So you say charlatans are not mere scammers or fraudsters. What defines a charlatan?

Quico Toro: Well, sure. A scammer or a fraudster is someone who comes into your life, takes advantage of you, and then disappears. They’re usually anonymous. Charlatans aren’t really like that. Charlatans are public figures. They operate out in the open under their own name, and they dig their claws into you. They can manipulate you over the long term.

What we found as we wrote the book is that there are all these people who make themselves into part of their victim’s identity, and that we think is really new.

Mina Kim: Oh, I want to dig into that some more. But before I do, why do you say that understanding charlatanism has never been more urgent?

Quico Toro: Well, because it used to be that charlatans really plied just a couple of trades. They were looking out for things that everybody wanted. Usually it was either a health thing — like a cure-all, snake oil — because so many people are sick and just want to believe they can get better. Or get-rich-quick schemes. For thousands of years, those were the two breeds of charlatans you found in the wild.

But as technology has changed, it’s allowed this very broad number of people to microtarget people for the specific things that make them them — for their dreams, their baseline commitments. So there are many more different types of charlatans now, targeting you in all kinds of ways.

Mina Kim: Yeah, it’s interesting too. You also say that tech has increased social isolation. Why does that help a charlatan?

Quico Toro: That’s right. It’s both things. When people don’t have solid communities around them, it’s much easier for them to be victimized. You don’t have that second filter — that person in your life who you might say, “Hey, this guy is telling me this or trying to sell me this idea. It sounds great, I’m so excited.”

If you have a solid network of community that you’re embedded in, there’s more likely to be somebody there to raise a flag, to make you think again, to help you avoid being victimized. But we’ve heard a lot about the loneliness epidemic, about post-COVID isolation, about people going out less. People are embedded in fewer thriving social networks. That makes them easy pickings for charlatans.

Mina Kim: Let me invite listeners in. 866-733-6786 is the number. What comes to mind when you think of a charlatan? What have you noticed about how charlatans operate? Have you or someone close to you ever been influenced by one? You can also email forum@kqed.org, or find us on Discord, BlueSky, Facebook, Instagram, or Threads @KQEDForum.

Okay, Quico, let’s dig into what you mentioned earlier about the strategy of many charlatans. You say one of their key abilities is to exploit people’s deep longings or dreams. Give us some examples.

Quico Toro: That’s right. If you’re a normal person with a psychologically normal makeup, there are a few ideas — a few commitments in your life — that you really can’t stand to see questioned. And those can be really varied. If you’re a religious person, it might be your faith in God. If you’re spiritual, it might be your faith in communion with metacosmic forces. It might be wellness and the feeling that you can be well in your body in the world. Or racial reconciliation. Or “making America great again.”

It can be so many different things. But for almost everybody, there is that one idea that is just core to who you think you are. It’s the idea that, if it weren’t true, the world wouldn’t make sense and you wouldn’t want to live in it.

What charlatans do is embody one of these ideas. Then the people who share those ideas come to them. This is the key thing we noticed: charlatans aren’t in the persuasion business. They’re not trying to get you to believe something you don’t already believe. They’re flattering a set of prior beliefs that some group already holds very dear. And they know that if they do this with enough charisma, charm, and persuasiveness, the marks will line up to be victimized. And they’ll want to be victimized.

Mina Kim: You profile more than twenty charlatans from all walks of life, all different ages and eras. One of the ones I’d like you to tell us about first is Mehmet Aydin, who you said tapped into the dream of people in Turkey who wanted to connect with their nation’s agricultural soil. Can you tell us about Mehmet?

Quico Toro: Right. Mehmet Aydin — it’s such an interesting story. He was a religious-school dropout from a little town south of Istanbul. Really had nothing going for him. Back in 2013, 2014 — if you remember FarmVille, the Facebook game where you simulated a farm — he was playing that, hooked on it, like a lot of people.

And he had this brilliant idea. He realized the game was fun, but it was all plastic. No real cows, no real farms, no dirt or soil. He was from a farm town, but now living in the city, and he could connect with rural people in Turkey who had an idealized vision of the rural lives their parents or grandparents had lived.

So he built Farm Bank, which was like a FarmVille rip-off game, but different. He said Farm Bank would have real farms connected to it. You could invest in real farms in Turkey and support Turkish agriculture, while playing this fun game on Facebook.

Of course, it was a Ponzi scheme. He took money from new subscribers to pay “profits” to earlier ones. But this created a huge mania in Turkey. People rushed in. He advertised on TV with nationalist messages about how wonderful farm life was in Turkey and how people needed to reconnect with their rural roots. At a certain point, Farm Bank fever seemed to take over.

But eventually, Aydin disappeared. He was buying real farms, but the profits were fake. Turkish media covered it wall-to-wall for months in 2017 and 2018. Rumors flew: he was in Kazakhstan, Canada, El Salvador. In reality, he went to Uruguay, where someone filmed him badly driving a white Ferrari. Then he fled again, ending up in Brazil, where he was arrested, extradited back to Turkey, and sentenced to — I don’t remember the exact number — but upward of 40,000 years in prison for fraud.

Mina Kim: Wow. And I’m struck by how you said you don’t blame people for believing in him. You argue we shouldn’t dismiss victims as ignorant or uneducated, right?

Quico Toro: Exactly. We built the book around stories from different geographies — Turkey, yes, but also the U.S., Brazil, Holland, Costa Rica, all over. And the victims ranged from poor to middle-class to rich, educated and less educated.

What you see is that no category of people is protected. If a pitch connects with that inner sense of identity — those dreams that make life make sense — anybody can be had.

When we hear a charlatan story for the first time, there’s a tendency to get judgmental, because if you don’t share the dream they exploited, it just looks ridiculous. Obvious. That gives us a false sense of security — “I’d never fall for that.” But spotting scams that target other people’s dreams doesn’t protect you from a pitch that targets your own.

Mina Kim: After the break, we’ll get to some of the pitfalls we have ingrained in us that don’t stop us from being taken in by charlatans. We’re talking with Quico Toro, author with Moisés Naím of Charlatans: How Grifters, Swindlers, and Hucksters Bamboozle the Media, the Markets, and the Masses.

He’s also director of climate repair at the Anthropocene Institute and founder of Caracas Chronicles, an independent news organization covering Venezuela.

Listeners, who comes to mind when you think of a charlatan? What have you noticed about how charlatans operate? Have you or someone close to you ever been influenced by one?