This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Mina Kim: Welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim. Have you ever had a relationship tested by a grueling physical experience — a wilderness trip that went terribly wrong, maybe, or a natural disaster that upended your life with a significant other?

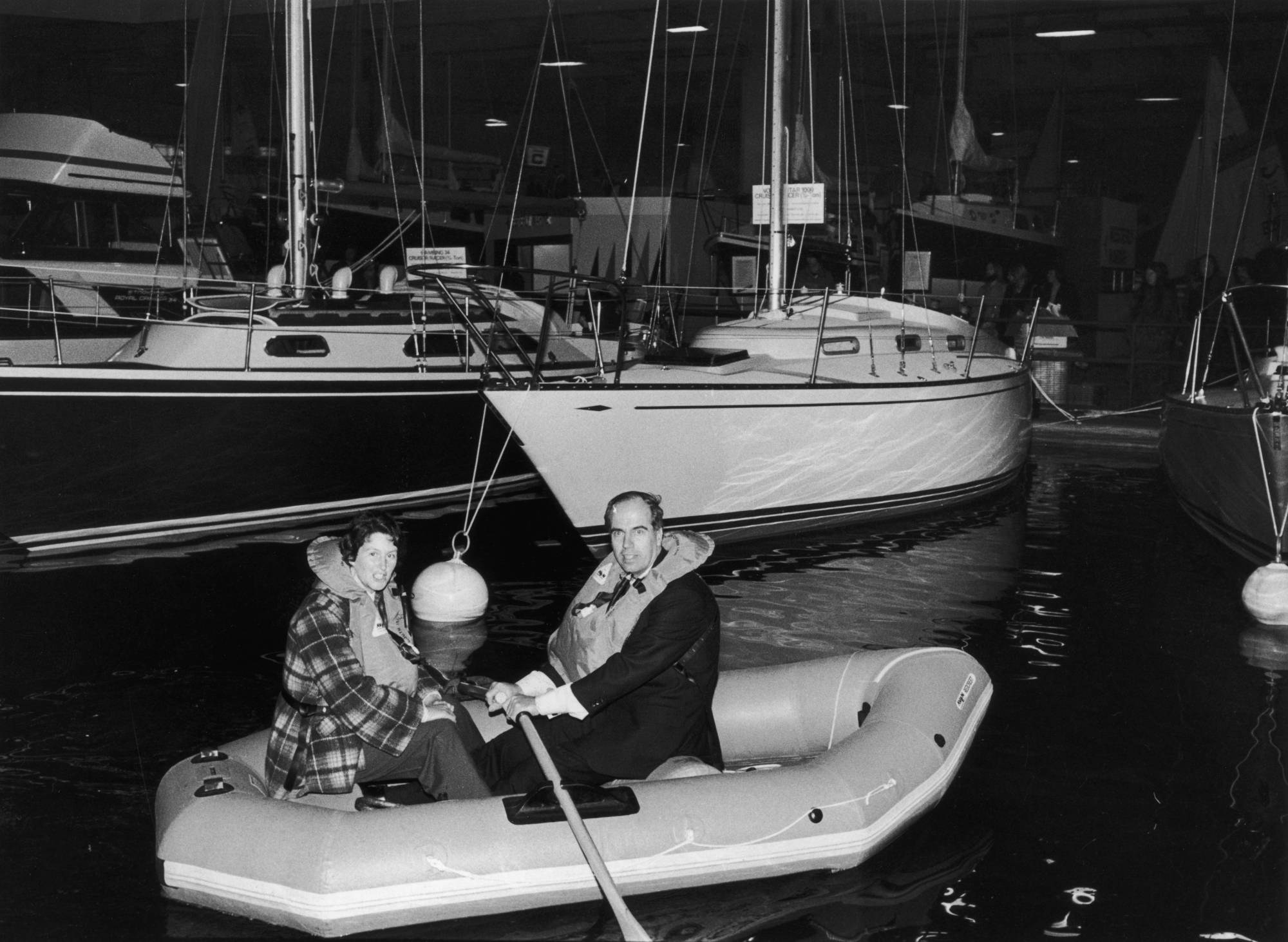

In 1972, a whale struck Maurice and Maralyn Bailey’s boat, leaving the couple stranded on a tiny rubber raft in the Pacific Ocean for months. Journalist Sophie Elmhirst looks at how they survived together — starving and pushed to their absolute limits. She joins me now. Sophie, welcome to Forum.

Sophie Elmhirst: Hi. Thank you for having me.

Mina Kim: Well, thank you for being here. How did you first discover Maurice and Maralyn Bailey’s story, and why did it speak to you?

Sophie Elmhirst: Well, as you said, I’m a journalist. I was researching a story in the middle of the pandemic, during lockdown, and I was looking into stories of people trying to escape the land in different ways and live on water.

I came across their story on a website devoted to castaway stories — people who had somehow been shipwrecked or ended up adrift. Among all these photographs of grizzled-looking men, there was a picture of a man and a woman, and she caught my eye. I wanted to know what happened to them.

Once I discovered what had happened — quite how long and how extreme their experience was, being adrift on the Pacific for nearly four months — I felt compelled to tell it. But not least because it was also the story of a marriage. I immediately started thinking: what would it be like not just to go through that, but to go through it with your partner, with your spouse? That was my way in — wanting to understand that.

Mina Kim: Yeah. One of the other things that’s kind of extraordinary is how very different they were as people, right?

Sophie Elmhirst: You couldn’t get more different in some ways. Although, on another level — and maybe this speaks to all of our relationships — they were very well-suited in ways that made them seem like opposites.

He was an awkward, lonely, cantankerous man in many respects. She was a live wire, brimming with confidence, someone who made things happen. She called the shots in their relationship. But when they were adrift, everything went up in the air.

While he had always been the captain when everything was going well on their boat, their roles reversed once they were struggling. Seeing how their dynamics changed in crisis was really interesting.

Mina Kim: In some of your interviews about Maurice and Maralyn, you say some people were mystified by what Maralyn saw in Maurice. What do you think it was?

Sophie Elmhirst: It’s a really good question. I got that from talking to her relatives, like her half-sister Pat, who still says, “We were never completely sure. We never really understood it.”

But I think what he gave her — when they met in the 1960s, not swinging London but Derby, a town in the middle of England — was the chance to live a different kind of life. She grew up in a conventional household, expected to stay home until she married and then lead a limited domestic life.

He was older, already an adventurer — climbing mountains, flying planes, sailing. These were things she’d never done. He gave her a taste of freedom and adventure, a way out of that domestic sphere. At the same time, she introduced him to the world socially, because poor Maurice didn’t have the greatest social skills.

Mina Kim: It was really Maralyn who convinced Maurice, right, that they could achieve his dream of building a boat and living on it?

Sophie Elmhirst: Absolutely. If it had been left to him, he admits they probably never would have done the trip. She was the one who conceived the idea: “If we want to get out of this small, everyday life in Derby, we’re going to immigrate to New Zealand. Let’s sell the house, sell everything we own, build a boat, and sail there.”

It was a radical idea, and most people would have abandoned it. But she drove them through it. That continued both in their ordinary lives and in this great escapade. She was the one always coming up with schemes to keep them distracted, to keep their spirits going. She was the engine behind that.

Mina Kim: Yeah. It was fascinating to read about the role she played — not only in how they survived the shipwreck but also in believing in their ability to commission this 31-foot sailboat they called the Auralyn. You wrote that they almost thought of it like a child?

Sophie Elmhirst: Yes. One unusual thing about them was that they were very clear when they married that they didn’t want children. Maurice had always felt that way. He never wanted to continue his line, and to his surprise, Maralyn agreed.

So when they embarked on this adventure and built the boat — which they named Auralyn, a combination of their names — it became as close to their offspring as they would ever have. They tended to it and loved it. With a boat, you have to — it requires constant maintenance and care. It really was like their child.

So when the whale hit her and she went down, aside from everything else, it was a huge loss, a grief for them.

Mina Kim: Yes. This was nine months after they left England for their trip to New Zealand. They had made it through the Panama Canal and into the Pacific. Could you read the passage when disaster strikes and a whale breaches at the exact location of the boat?

Sophie Elmhirst: The water was up to their knees, and the cupboards were starting to spring open, unleashing their contents. Eggs and tins bobbed around them. They looked at each other. Maurice fetched the life raft and the dinghy, then collected as many freshwater containers as he could find. Maralyn waded round the galley, filling two sail bags with their things: two plastic bowls, a bucket, their emergency bag, passports, a camera, a torch, their oilskins, her diary, two books, two dictionaries, and Maurice’s navigational tools — his nautical almanac and sight reduction tables, his chart, sextant, compass, and logbook. They worked fast and in silence, strangely calm as the water rose. It wasn’t easy gathering possessions from a vessel filling with ocean. Ten minutes it took to gather what they could. Then they climbed off the boat into the dinghy. Around them, the Pacific was moving gently. Maralyn watched cushions she’d spent hours embroidering float away on the waves. Their boat settled low in the ocean, then lower. Maralyn found her camera and took a picture of Maurice, who was sitting in front of her, shirtless. He turned back to look at her, every muscle of his back delineated under the harsh glare of the sun, wearing an expression not of fear, not yet, but of a kind of taut blankness, as if he’d not quite grasped what was taking place — the sight of their boat tipping to one side as she sank in the middle of the ocean.

Mina Kim: That’s my guest, Sophie Elmhirst, reading from her new book A Marriage at Sea: A True Story of Love, Obsession, and Shipwreck. Sophie also writes regularly for The Guardian, The Long Read, and The Economist.

A Marriage at Sea tells the story of Maurice and Maralyn Bailey, who found themselves stranded on a tiny rubber raft in the Pacific in 1972 after a whale collided with their boat — starving and pushed to their absolute limits.

And listeners, I want to know: do you think your marriage would survive such a shipwreck? Have you ever had a relationship tested by extreme conditions or grueling physical experiences? What happened? And if you’ve had to survive an extreme condition, what did you learn about what we really need to live?

Email us at forum@kqed.org. Find us on Discord, Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, or Threads, or call us at 866-733-6786. Stay with us. I’m Mina Kim.