This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

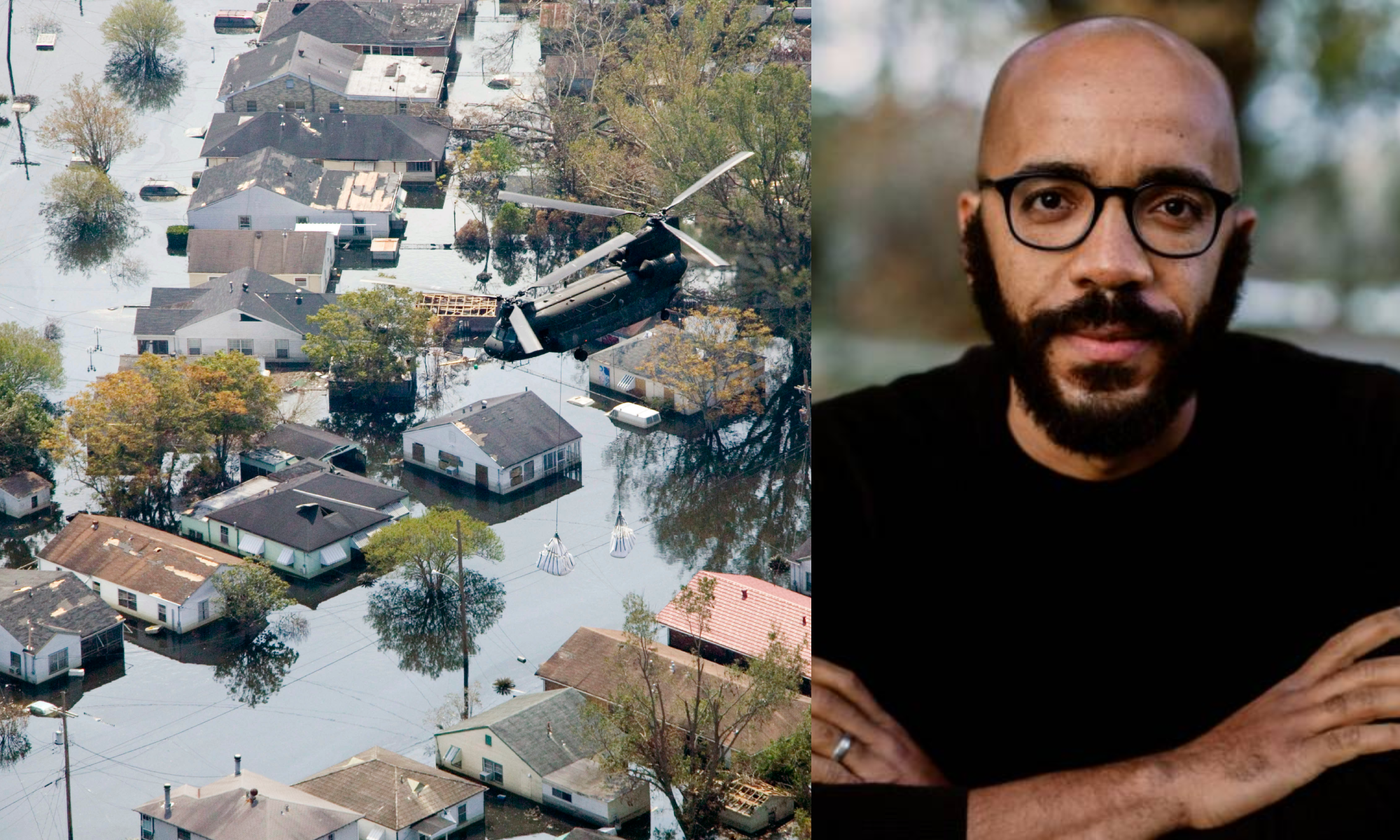

Mina Kim: Welcome to Forum. I’m Mina Kim. It’s been two decades since Hurricane Katrina brought death and destruction to New Orleans and the Gulf Coast region. Fourteen hundred people died, many in New Orleans, where levees maintained by the federal government collapsed under the force of the storm surge.

My guest, Clint Smith, had just turned seventeen when his family packed their duffle bags with a few days’ worth of clothes and evacuated to Houston to stay with family before the storm made landfall on August 29, 2005. Smith’s new piece for The Atlantic is called Twenty Years After the Storm.

And listeners, what are your memories of when Hurricane Katrina struck? Clint, it’s so nice to have you back on Forum.

Clint Smith: It’s so good to be here.

Mina Kim: So when you left your home to drive to Houston, did you have any sense of how bad the storm would be?

Clint Smith: You know, part of what’s important for people to know is that evacuating for hurricanes was part of the normal cadence of my life—and of so many New Orleanians’ lives. We live in perhaps the most vulnerable area in the U.S. for hurricanes, or among the most vulnerable.

Every other year of my childhood, we’d be told a tropical storm or hurricane was coming, and we’d have to pack some bags, evacuate to Houston or Baton Rouge or Jackson, Mississippi. We’d stay for a few days. Usually, for me, it was: I got a couple extra days to study for my math test, or I got to hang out with my cousins.

But it became clear with Katrina that we were dealing with something different. I became aware of that when my dad woke up in the middle of the night. This was actually the day before Ray Nagin said New Orleans was under a mandatory evacuation order—the first time that had ever happened in the city’s history.

My dad told us we needed to pack our photo albums and our paintings from local New Orleans artists, put them in plastic bags, and bring them to the second floor. That was different than anything we had done before. Even without him saying so explicitly, I think that act signaled we were dealing with something different.

Mina Kim: Yeah. Did that ultimately save them from being too damaged?

Clint Smith: It did. I’m so grateful. In my reporting, I do a lot of work on historical memory—how we remember and think about history and historical sites.

I’ve traveled to Rwanda to write about how they remember the genocide. I’ve written a book about how the U.S. remembers slavery. I have a forthcoming book about how different countries around the world remember World War II.

One of the things that comes up over and over: I remember a woman in Rwanda who told me one of the things she grieves most, in addition to losing her family, is that she has no pictures of her childhood. She has no pictures of her parents. She can’t remember what they looked like.

You hear the same in Korea. You hear the same in Germany. So I say that because it makes me grateful my father had the foresight to save our photo albums. They’re such a cherished part of how our family holds on to memories that mean the most to us.

Mina Kim: Yeah. You wouldn’t be able to go back to your home until October, even though you were one of the first families allowed back. And you write about feeling nervous. Why?

Clint Smith: We evacuated and ended up in Houston, Texas, where we stayed with my aunt, uncle, and cousin. For about a week we were glued to CNN, watching the city slowly—and then quickly—become submerged.

In addition to harrowing images of people at the Superdome, at the convention center, on top of bridges and roofs, and bodies floating in the water, I remember seeing the church we went to underwater. I remember seeing the grocery store underwater. I remember seeing my school underwater.

These were all places that were part of the constellation of my neighborhood and community. Even without seeing my home, I kind of knew what had happened. But you still have that hope—that maybe, because you haven’t seen it yourself, your home might have been spared. Ultimately, when we got back, we realized that was not the case.

Mina Kim: Yeah. When you approached your home, the outside had an orange spray-painted X. What did it mean?

Clint Smith: This was a ubiquitous fixture of the New Orleans landscape after Katrina. Almost every home had an orange spray-painted X. One quadrant represented the date the home was searched, one quadrant the team that searched it, another quadrant indicated hazards, and the bottom quadrant the number of bodies found inside.

On our door, it said zero because no bodies were found inside. But I’ll always remember driving into the city and the haunting stillness everywhere. It looked like a bomb had gone off—tree trunks uprooted, branches and cars strewn across streets.

You’d pass houses and mostly see zeros. But every once in a while, you’d see a different number—a one, two, or three—meant to represent how many people, dead or alive, were found inside. I’m haunted to this day, wondering whether they were people rescued or bodies that had long since perished.

Mina Kim: What was it like for you when you went into your home?

Clint Smith: We went back in hazmat suits and gas masks—my mother, father, sister, and I. My little brother was too young to join us. The door was ajar because the search and rescue team had already been there.

As we walked in, the smell knocked me back. Blue-green mold climbed the walls up to the ceiling. The freezer and refrigerator were ajar, food spilled across the floor. Picture frames were scattered. The television in the living room was flipped on its face.

A chandelier hung from the ceiling with one of our dining room chairs tangled in it. Our mahogany dining table had been lifted by floodwaters and floated from the dining room into the living room.

My birthday had been just a few days before the storm. Every year, I got a vanilla almond cake with pineapple filling from Adrian’s Bakery, a neighborhood tradition. When we evacuated, it was sitting on the dining room table inside its case.

When we came back, the house was destroyed in every way. But because the table had floated, the items on top—including the cake—were miraculously spared. It was such a strange experience: amid all that chaos, the cake looked untouched.

Mina Kim: Well, let me invite our listeners into the conversation. We’re talking with Clint Smith, who lived in New Orleans and was seventeen years old when Hurricane Katrina made landfall there.

Listeners, what do you remember about Hurricane Katrina—the images, the news reports, if you were looking at it from afar? Has your home or neighborhood been destroyed by a natural disaster—a flood, a fire? Do Clint’s descriptions of the sights, smells, and feelings resonate with you?

You can email forum@kqed.org, find us on Discord, Bluesky, Facebook, Instagram, or Threads at KQED Forum. Call us at 866-733-6786.

For me here in California, wildfires have been the predominant natural disaster I’ve covered in recent years. Flood damage is different, of course. But your account makes me think of the through line: confronting deep loss when you return to a destroyed home, and the dramatic demarcation of before and after.

Clint Smith: Yeah. That’s absolutely right. My life was demarcated by Katrina, and I think that’s true for so many people from New Orleans.

I write in the piece about how for so many people, when folks invoke a memory—say, “Were you at this place?” or “Did you go to this event?”—the first thing people ask is: “Was that before or after the storm?”

COVID has become a similar marker of time for many of us. For others who’ve experienced disasters like wildfires, it’s the same thing. But Katrina is the primary marker for me.

I was seventeen then, and I’m thirty-seven now. In many ways, Katrina split my life in half—marking the innocence and clarity of childhood versus the realities of adulthood. It gave me a clearer way of understanding the racial and social inequalities in this country—things I hadn’t been as aware of, or hadn’t witnessed on that scale.

Mina Kim: We’re talking with poet and staff writer for The Atlantic, Clint Smith, about twenty years after Hurricane Katrina.

Listeners, you can join the conversation by emailing forum@kqed.org, finding us on social media at KQED Forum, or calling 866-733-6786. Stay with us. I’m Mina Kim.