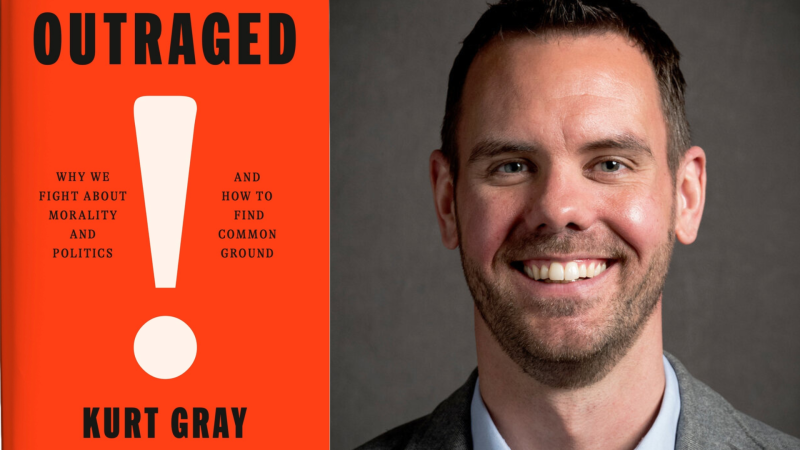

What is outrage, and what triggers it in us? When someone violates our moral sense, we might bristle with rage or thirst for retribution but UNC psychology professor Kurt Gray wants us to understand that the other side is also motivated by moral convictions, even if they don’t make sense to us right away. We talk to Gray about how understanding the psychology of moral conflicts can help us better manage them. His new book is “Outraged: Why We Fight About Morality and Politics and How to Find Common Ground.”

Kurt Gray Explores the Psychology of Outrage

Guests:

Kurt Gray, social psychologist and professor of psychology and neuroscience, University of North Carolina; director, Deepest Beliefs Lab and the Center for the Science of Moral Understanding

Show Highlights

Social psychologist Kurt Gray explores moral outrage — the intense anger triggered when someone appears to violate fundamental values of decency, courage, or compassion. While outrage often deepens political divides, Gray argues that understanding its origins can help bridge them.

The Roots of Moral Outrage

Moral outrage, Gray explains, stems from a deep conviction that one’s side is not only right but also fighting against real harm. “The other side isn’t just wrong,” he says, “they’re causing harm or complicit in it.” This instinct, he notes, evolved as a survival mechanism — an innate vigilance that once protected early humans but now fixates on perceived moral threats.

How We Define Harm

Moral conflict often boils down to differing views on harm and victimhood.

“Conservatives tend to see harm in individual terms,” Gray explains. “It doesn’t matter if you’re rich or poor, Black or white — we all suffer. If we’re cut with a knife, we all bleed. It’s an individualistic view of victimhood.”

Progressives, he says, take a more systemic view. They focus on harm inflicted on entire groups, such as racial minorities or marginalized communities. These competing perspectives shape how each side interprets injustice — and fuel political polarization.

Social Media’s Role in Amplifying Outrage

“Social media is mostly bad for us,” Gray says. “It amplifies outrage. Algorithms are built to get us angry.”

By prioritizing content that provokes strong emotions, social media creates an illusion of constant crisis. Gray also points out that modern society’s relative safety means that even minor perceived harms stand out more, intensifying outrage over issues that past generations might have overlooked.

Bridging Divides

To move forward, Gray emphasizes the need to engage with opposing viewpoints.

“If we’re on one side, we need to understand the other,” he says. “A nation with only one party is a dictatorship. If we want to compromise, we have to start by understanding what the other side is thinking.”

He cites historical movements as examples. “Civil rights. Women’s suffrage. These movements succeeded by recognizing the concerns of the other side, finding allies, and building coalitions.”

Managing Relationship in a Polarized World

Outrage often strains personal relationships, but perspective-taking can help.

“Half of America isn’t trying to destroy you or your values,” Gray says. “Most people just want things to work — they want their families to thrive and for milk to be affordable. Realizing this makes it easier to be a little calmer, a little kinder.”

Practical Tools for Understanding Others

Gray advocates for moral humility — the ability to question one’s absolute certainty.

“Instead of thinking, ‘I’m 100% right and you’re 0% right,’ try shifting to, ‘I’m 99% right.’ That’s still really high, but it leaves just enough room to learn from someone else.”

He also encourages engaging with people who think differently, even in small ways. “Part of organizing for change is understanding how others think — what they actually feel and fear. That knowledge gives you a game plan for moving forward.”

This content was edited by the Forum production team but was generated with the help of AI.