We may be a nation of individualists, every man and woman a maverick in his or her own heart, but you'd never know it to read our recipes, so rigidly do we adhere to a generic, codified blandness in laying our how-tos.

We may be a nation of individualists, every man and woman a maverick in his or her own heart, but you'd never know it to read our recipes, so rigidly do we adhere to a generic, codified blandness in laying our how-tos.

By contrast, those stiff-upper-lip Brits kick over the traces when they start to mix and fry. Nigella Lawson, Sybil Kapoor, Tamsin Day-Lewis, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, Dan Lepard, even éminences grises like Elizabeth David and Patience Gray: not for these writers the strict nothing-but-the-facts-ma'am method of American cookbooks. Across the pond, lively verbs and their adverbial companions shimmy freely in recipe methods. Even adjectives get their due. My favorite? Moreish, because whatever it is, you must have one more bite. Where Americans are folksy, British writers are droll.

Granted, I tend to read those written by authors with literary or journalistic backgrounds, who sift and measure their prose with as much diligence as they do their self-rising flour and diced courgettes. (Ah, those courgettes! Those aubergines! That black treacle! All almost the same as zucchini, eggplant, and molasses, but linguistically shifted just enough to nudge the reader into a right-hand driver's seat.)

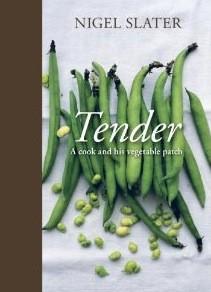

And one of the best is Nigel Slater, whose latest work Tender: A Cook and His Vegetable Patch was just released in an American edition by Berkeley's Ten Speed Press. This beautifully designed, chocolate-brown clothbound volume (complete with silvery place-keeping ribbon) is a celebration of the production of the slim but plant-packed garden of Slater's London townhouse. As dedicated an organic gardener as he may be, Slater makes no pretensions to urban self-sufficiency in his smallish backyard. As he writes,

"I have sown somewhat more than I have reaped. But as somewhere to watch things grow, a place to tend and nurture, to sit and eat, to drink and think, to taste and smell, and most importantly to understand the unity of growing, cooking, and eating, it is a monumental success. At least it is to me."

Slater, a longtime columnist for The Observer and the author of 10 cookbooks, is known in this country (if he's known at all) for his two most personal books, The Kitchen Diaries, a week-by-week seasonal calendar of what he was cooking and eating at home, and the childhood memoir Toast--The Story of a Boy's Hunger. His writing style is vivid and individual without being exactly personal. Reading this book is like wandering though an idiosyncratically decorated house: this lamp, this shell, this book reveals taste and history more succinctly than any long-winded curriculum vitae.