The Mill Valley Film Festival inhabits a rare “goldilocks” zone within the cinematic universe, with the smart good fortune of arriving as summer turns to fall and Hollywood gears up for Oscar gold. The festival manages to snag more than its fair share of prestigious premieres weeks or months before they become available to the rest of us, attracting the attention of A-list stars willing to spend a couple of days being feted in tony, upscale Marin. (Twenty-sixteen is no different; the festival guest list includes Amy Adams, Nicole Kidman, Gael Garcia Bernal, Aaron Eckhart, Julie Dash and Ewan McGregor among dozens of glittering others.) Most likely, part of the fest's draw is the food and wine on tap in a region famous for -- well -- food and wine.

In a fitting pairing, this year’s festival features a small selection of films detailing the exploits of international celebrity chefs and restaurateurs. Anyone who has viewed even a small number of food documentaries knows that the genre has developed a very strong sensual style of its own. One doesn’t just take a camera into a kitchen and uncover magic in the making. Food preparation doesn’t often look that appetizing. There is an art to the lighting and presentation of the process that has been refined since the mid-1960s. Now we find ourselves in an age where the glories of food are regularly celebrated in dazzling cinematic style. All three of the films featured in Mill Valley’s culinary sidebar present their subjects in sumptuous detail. They are gorgeous and absorbing, illuminating activities and slices of history, while expanding ideas about what constitutes nourishment.

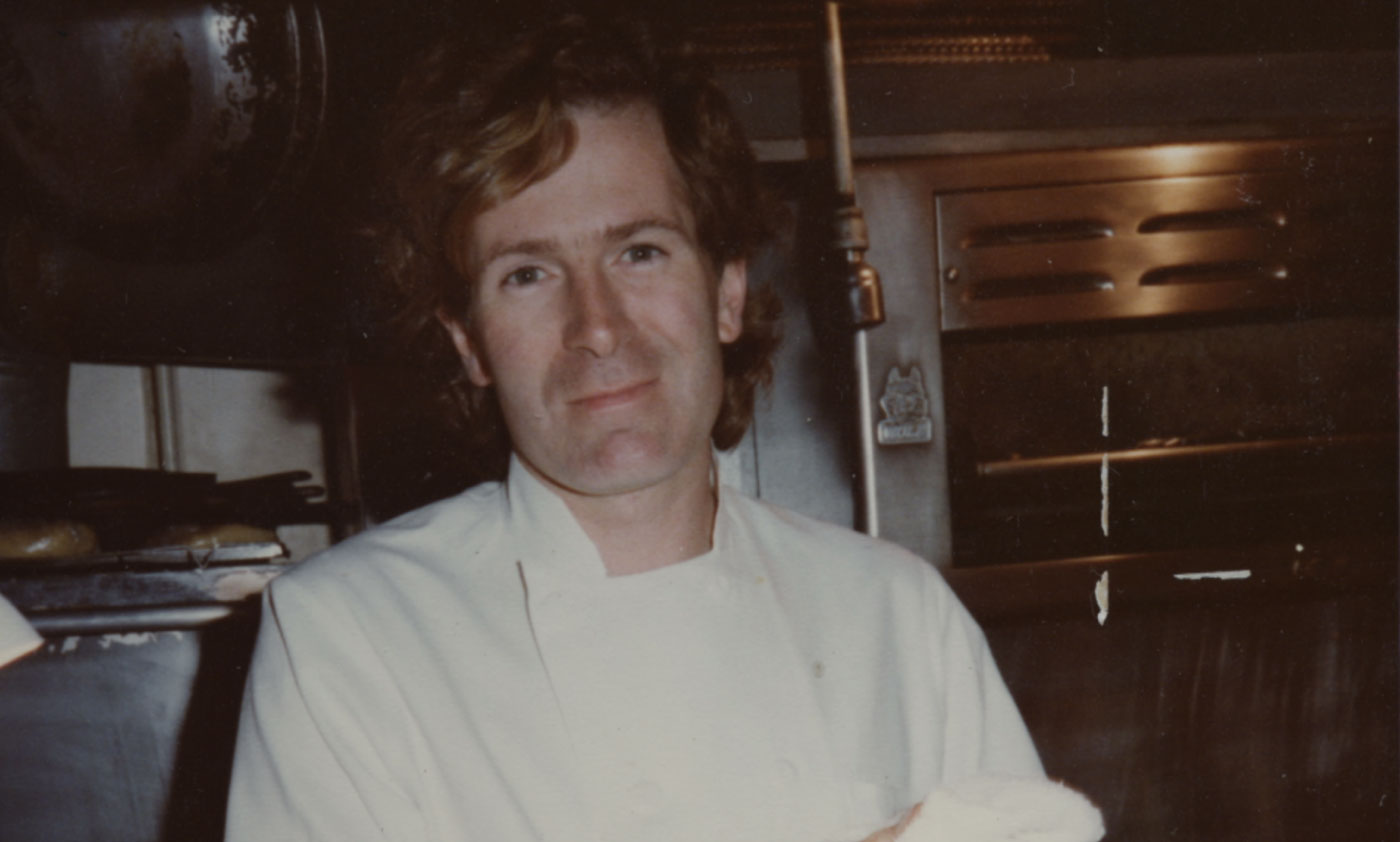

In Lydia Tenaglia’s Jeremiah Tower: The Last Magnificent, the very personal struggles of a legendary celebrity chef are delicately exposed. The film is almost like a therapy session, a journey into the subconscious motivations of a complicated man, beginning with lush reenactments of childhood trauma. Tower, the son of wealthy Brits, spent much of his life traveling the world first class -- with his family and without them. Apparently, the boy was left to his own devices in luxury liner cabins and four star hotel rooms from a very early age. He even lived for a time alone in a hotel suite until his parents realized that neither had enrolled him in school. While these adventures included (often inappropriate) sexual encounters, they also locate Tower’s love of food inside the kitchens of the world's most exclusive establishments. The young Tower seems to have eaten his feelings and later on would express his affection for friends through a kind of regurgitation (that sounds awful, I know) in the kitchen. He recreated from memory the dishes of his childhood in an attempt to conjure those early feelings of comfort for himself and his guests.

Tower is, and apparently always has been, a capital-R Romantic; an overwhelming sense of melancholy hangs over the film. He seems to have been born out of time, carrying deep inside a longing for a lost aesthetic age. Most BAB readers will know the outline of the chef’s history. Having graduated from Harvard (his interest was in underwater architecture), Tower’s family promptly cut him loose financially. In search of a job, he ended up at Berkeley's Chez Panisse in 1972. At the time, it was a struggling hangout for Alice Waters and her crew, described by one character in the film as a “hippie, drug-ridden explosion in a playpen.” Gorgeous old film footage captures a sense of wild abandon and innocence at the famed restaurant.

Tower brought his ideas about food from a lifetime of travel to Chez Panisse and within a few years helped put it on the map. This being Berkeley in the 1970s, the endeavor is described as something of an orgy — sex, drugs, love, food, creation, companionship, drama and more sex. The relationship between Waters and Tower included enough heat to create a legend, spark a food movement, and unfortunately ended in a very public feud. (Saint Alice is silent -- at least within the confines of this film -- on the subject.) Tower continued his rise and became the celebrity chef of San Francisco in the 1980s, opening the world-class Stars as a hangout for famous characters high and low.