At the heart of all collections, large or small, is a group of objects. We tend to take it for granted that these objects will be ordered, but the potential exists for the collection to be nothing other than a disorganized mess. The larger it gets, the more overwhelming. Systems of Collecting, on view this month at Kala Art Institute and Gallery, refocuses our attention on the physical and mental apparatuses that structure said collections.

Mari Andrews’s Studio Installation (2011) dominates the middle of the exhibition space. Separated but overlapping piles of leaves, pinecones, seedpods, rusted metal objects, and hundreds of other items cover a long, L-shaped table. Running parallel to the long leg of the table, about five feet away, stands a bookshelf of medium height full of glass jars with smaller, more delicate, or just plain dirtier materials, e.g. grass pods, butterfly wings, and dried clay. A slightly smaller bookshelf stuffed with lichen, moss and bark runs parallel to the short leg of the table, this time set about ten feet away. En masse, the installation is a “living” still life of dried, organic matter in rich earth tones, with the rusted remains of human artifacts thrown in for good measure.

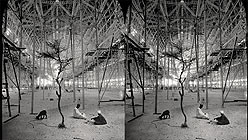

While beautiful to behold, Andrews’s installation overwhelms us with the gargantuan task of saving and collating these everyday objects. Stepping between the table and the bookshelves, a shift in perspective occurs. Various plastic bags and containers lie underneath the table; the collector’s detritus becomes apparent. It’s the perfect piece to pair with Matthew Troy Mullins’s series of huge watercolor and gouache paintings of various public and private collections, including the Prelinger Library here in the Bay Area. Mullins likes to zoom in on his subject matter, never showing it in its entirety. Entomology Archive (2010), for example, shows a portion of a flat file full of Coccidae specimens (scale insects). While the lower third of the painting features the pinned insects, the architecture of the collection draws the most attention. Shelves full of closed specimen boxes recede into a dark infinity.

This attention to structure (or systems) repeats throughout the exhibition. Vietnamese artist Binh Danh’s daguerrotypes of images from Cambodia and the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum force us to consider our own role in systems of violence against others; each silvery image reflects our curiosity back at us. Clever and subtle, Jeannie O’Connor recreates the experience of looking through glass by layering and repainting portions of images of the taxidermy bird collections at the Oxford University Museum using transparent photographic film. O’Connor intersperses these works with photographs of the Museum that feature juxtapositions of the building’s architecture and its contents, prioritizing the architecture.