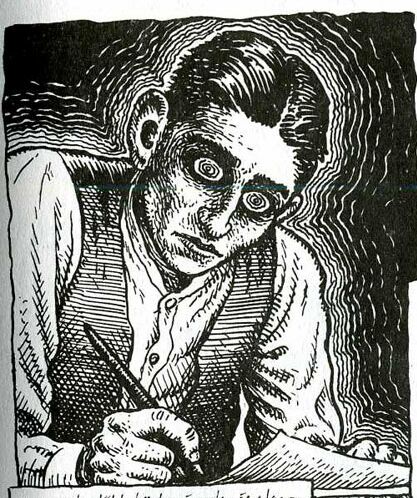

Benjamin Hale, the author behind The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore, recently visited the KQED studios to record an episode of The Writers’ Block, which will be released next week (listen to Benjamin’s reading). Until then, get to know him a little better with this Q+A, in which he talks about inspirational chimps and how Don Bluth scarred him as a child.

The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore deals with a chimp who has acquired spoken language (along with quite the impressive vocabulary) and I read that you’ve studied ancient Greek. What novel or author sparked your love affair with language?

Benjamin Hale: I haven’t studied Ancient Greek in years and my Greek’s pretty rusty now. But studying Greek made an enormous impact on me, and the way I think of language, aesthetics, grammar, and so on. Plato affected my thinking about time, semiotics, love, law and language more than any other philosopher. Somebody said that all philosophy is just Plato and footnotes. It’s true, you don’t really need anyone else. As for my love affair with language, Nabokov was the first writer whose English I absolutely fell in love with. I think he once described Lolita himself as “my love affair with the English language.”

You were inspired to write this book by visiting the Chicago zoo, but also by a haunting memory of a chimp with an Oedipus complex from a Jane Goodall documentary you watched as a child. Talk a little about that ape’s story and what it means to you.

BH: The story is from the documentary People of the Forest. A young male chimp, Flint, had a neurotic, obsessive attachment to his mother, Flo. He clung to his mother far past the age that most chimps stop, and so on. She died when he was an adolescent, of natural causes — she was old, it happens. But Flint could not accept her death. He dragged the body around with him for many days afterward, and allowed himself to waste away, refusing to eat or sleep. A while later, Jane Goodall found Flint dead beside a creek, having essentially starved himself to death. It was as if he died of grief. I was deeply disturbed by the idea that an animal could be just as crazy as a human being — that he could let his emotions get in the way of the evolutionary imperative to live, just like a human can. It says something powerful about the depth of animal consciousness, especially in a very complex, intelligent animal, like a chimp or a human being.