Editor’s note: This story is part of ‘Trans Bay: A History of San Francisco’s Gender-Diverse Community.’ From June 9–19, we’re publishing stories about transgender artists and activists who shaped culture from the 1890s to today.

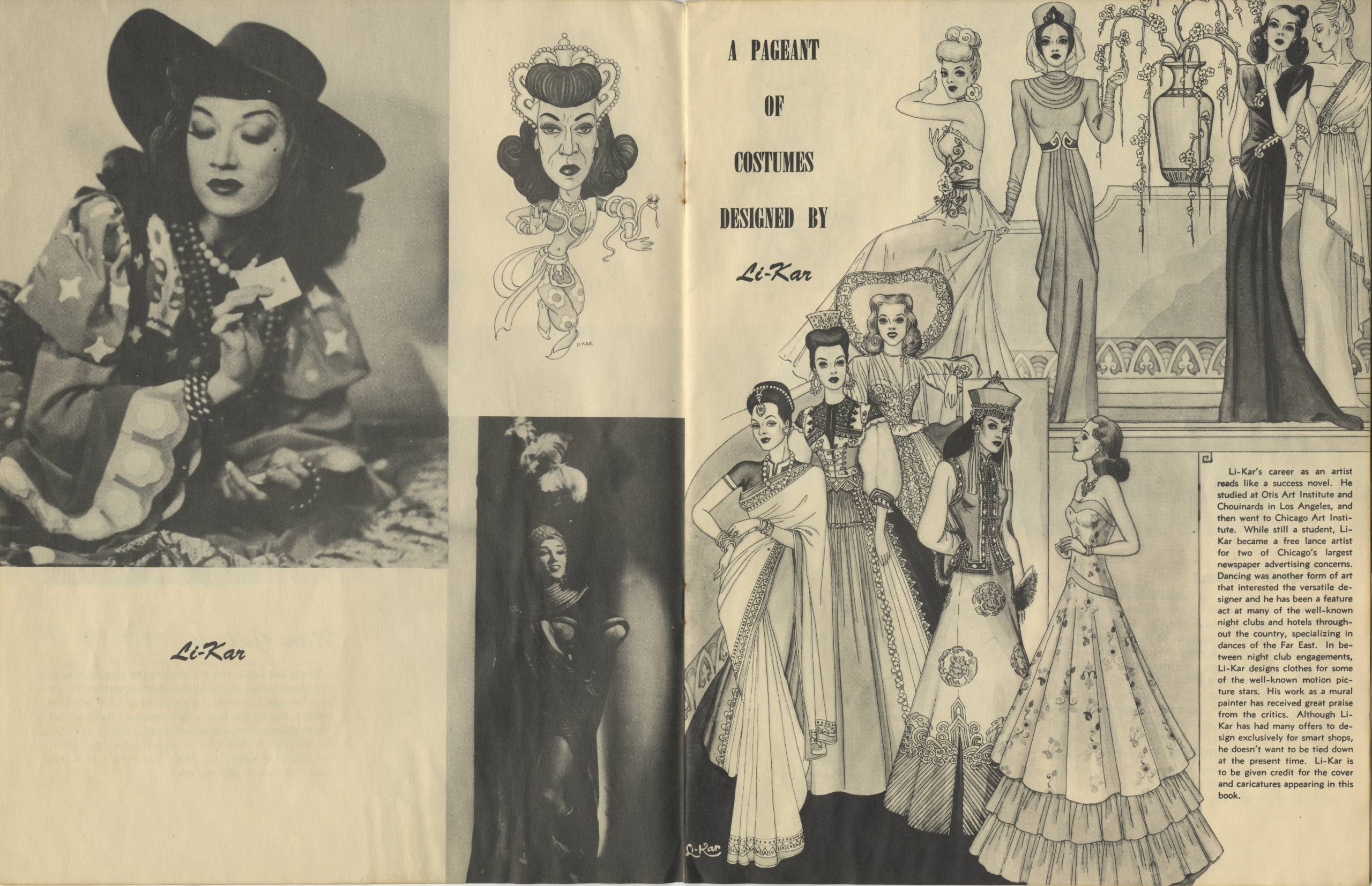

“The most interesting women are not women at all,” reads the back of a Finocchio’s souvenir magazine from the club’s early days. This, of course, was meant to be interpreted as a tongue-in-cheek nod to the anatomy of many of its performers — mostly men dressed in colorful gowns and shiny heels. Though Finocchio’s marketed itself to a straight audience and treated drag as a curiosity, for some trans women the venue became a haven where they could express their true gender identity without fear.

Almost exactly 89 years ago, on June 15, 1936, the first “female impersonators” set foot on the stage at 506 Broadway, the building that housed Finocchio’s up until its closure in 1999. Before relocating to this address, the bar was more of a speakeasy that sometimes featured drag performers, though that was enough for the police to take notice and raid the place. At its new location, above Enrico’s Café, the club flourished as it quickly gained notoriety for being the best venue to see men in gowns and wigs on the West Coast.

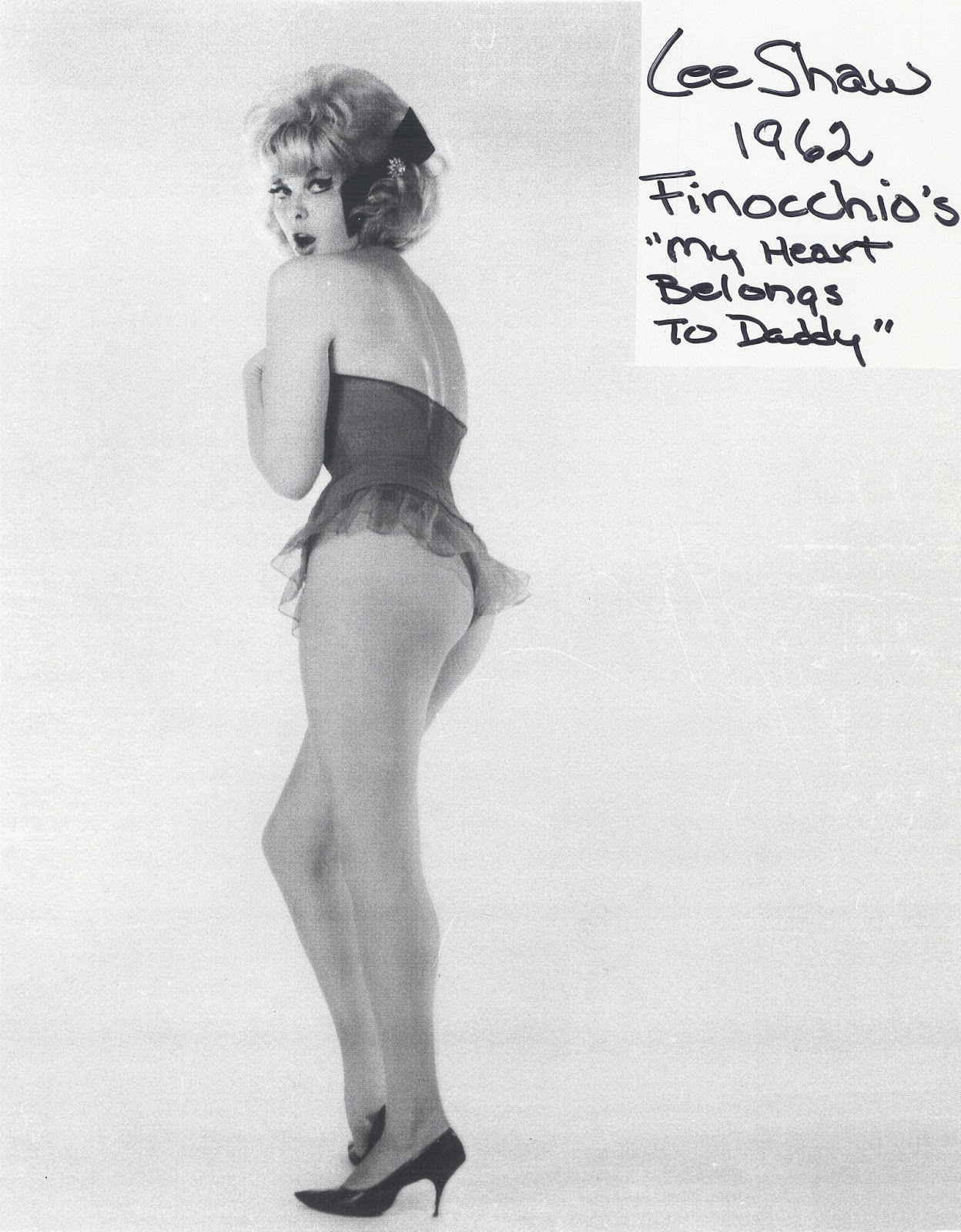

Word even spread among the celebrities that were often being impersonated by Finocchio’s performers. “Bette Davis and Lana Turner came to sit ringside,” wrote Aleshia Brevard, who performed at Finocchio’s under her stage moniker “Lee Shaw,” in her memoir. Liza Minnelli, Frank Sinatra, Ava Gardner, Judy Garland, Marilyn Monroe and more Hollywood royalty are said to have paid a visit to the club in its heyday.

“For me, Finocchio’s offered the first sense of true acceptance I’d ever known,” said Brevard of her time as a performer. A young trans woman, she appreciated the attention she was getting as a drag diva. “Several straight men wanted to date me; a few luckless female strippers wanted relationships; and more than a few intrigued military men were willing to dismiss the fact that I was a boy,” she wrote in The Woman I Was Not Born To Be: A Transsexual Journey.