Years ago, when food journalist Toni Tipton-Martin first started researching the history of African American cocktail recipes, she was struck by how few books were solely dedicated to that topic. Of course Tipton-Martin, who in the ’90s became the first Black food editor for a major American daily newspaper, is probably best known for her prodigious collection of African American cookbooks. Those hundreds of volumes, many of them rare, inspired and informed her two prior James Beard Award–winning books, The Jemima Code and Jubilee, which cast a spotlight on the unsung stories of Black cooks in America.

And yet the fact remained: “There are two books published in 1917 and 1919 by male bartenders, and then mixology disappears from the pages of Black cookbooks,” Tipton-Martin explains. “It’s only recently come back with any real gusto.”

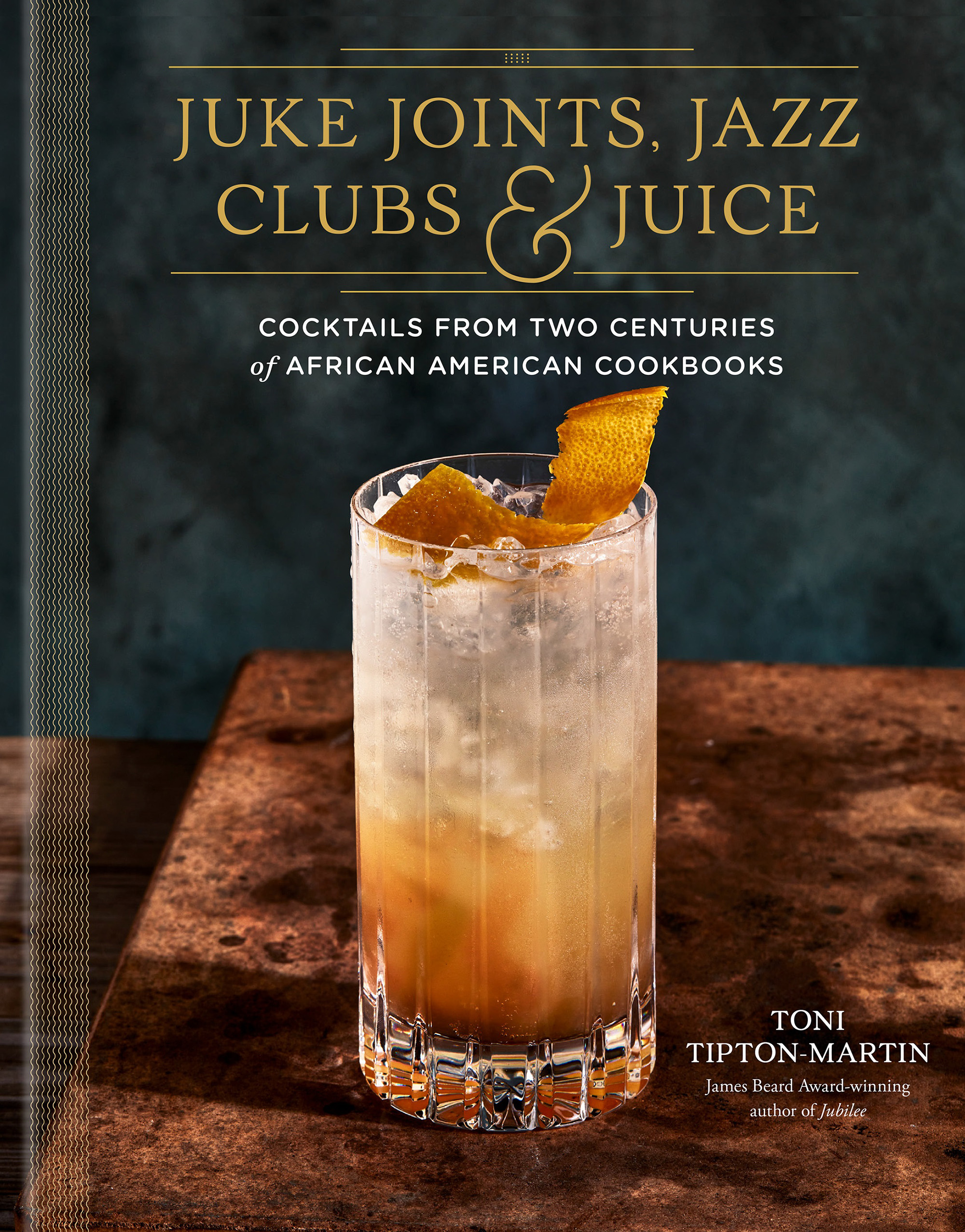

Tipton-Martin’s investigation into this long absence and oversight — which, no surprise, was largely tied to racism — forms the basis for her 2023 book, Juke Joints, Jazz Clubs & Juice. It is, on the one hand, a wide-spanning cocktail recipe book that features a whole kaleidoscope of juleps, rum punches and home-fermented wines inspired by recipes she found in 200 years’ worth of African American cookbooks, ranging from an 1827 domestic workers’ handbook to T-Pain’s compulsively readable Can I Mix You a Drink? (the rapper-turned-singer’s 2021 book of cocktails named after his own hit songs). More than that, it’s a celebration of all the mostly untold stories of how African Americans have helped shape this country’s cocktail culture.

The book is also the focus of “A Jazzed Up Evening with Toni Tipton-Martin,” a swanky May 10 dinner event at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora. Tipton-Martin will be on hand to give a talk. Tammy Hall, the Bay Area’s own Grammy-winning jazz pianist, will perform. And, naturally, there will be an opulent spread of food and drinks inspired by recipes from both Juke Joints and Jubilee: a California sherry cobbler cocktail, Savannah-style pickled shrimp, string beans a la Creole and more.

The event is part of MoAD’s long-running “Diaspora Dinner” series, curated by chef-in-residence Jocelyn Jackson. It’s the museum’s flagship fundraising event, known for bringing some of the country’s most prominent Black scholars and chefs to San Francisco. (Recent editions have featured food historian Jessica B. Harris and the Bay’s own Sarah Kirnon.)

“Black people were depicted in very negative and stereotyped ways in post-slavery America, in retaliation for freedom,” Tipton-Martin says. “So when Black people are portrayed in relation to spirits, they’re associated with debauchery — violent Black men, wild Black women, people wasting their money.” As a result, Black cookbook writers who wanted to prove their competence and expertise tended to avoid focusing too much on alcohol.

“Black people were depicted in very negative and stereotyped ways in post-slavery America, in retaliation for freedom,” Tipton-Martin says. “So when Black people are portrayed in relation to spirits, they’re associated with debauchery — violent Black men, wild Black women, people wasting their money.” As a result, Black cookbook writers who wanted to prove their competence and expertise tended to avoid focusing too much on alcohol.