Editor’s note: This story is part of ‘Trans Bay: A History of San Francisco’s Gender-Diverse Community.’ From June 9–19, we’re publishing stories about transgender artists and activists who shaped culture from the 1890s to today.

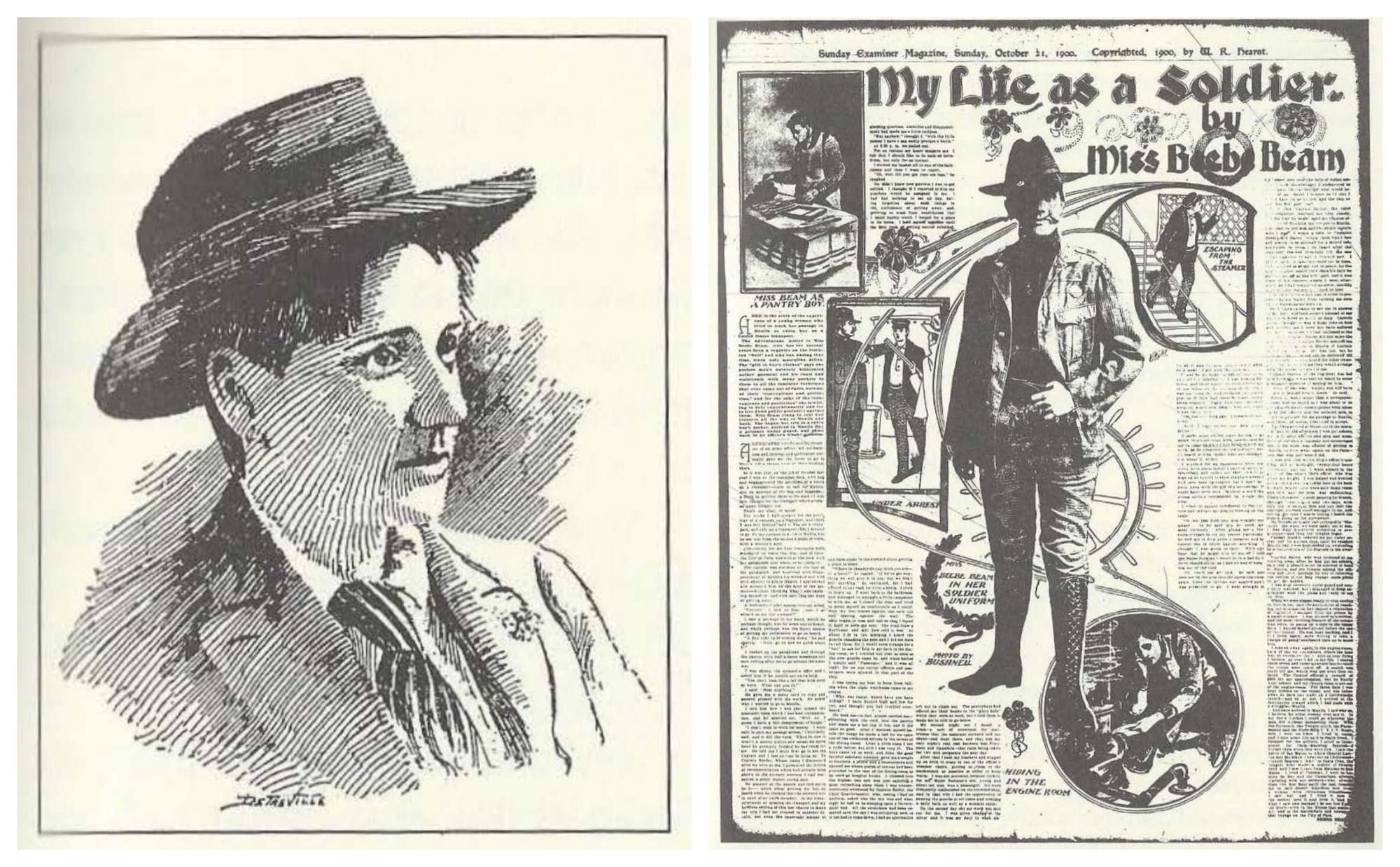

In 1906, after the earthquake and fires ravaged San Francisco, a young man stepped up to tend to the city’s injured and displaced. Jack Bee Garland was already an accredited nurse with the Red Cross who had received a medal for his service in the Philippines during the Spanish-American war. (Women were not permitted to serve as nurses during the conflict. Garland smuggled his way there.) It came as second nature to Garland then, to help his fellow San Franciscans in a time of great crisis.

What most of the people he helped did not know at the time was that Garland had been assigned female at birth. By the time of the earthquake, he had been living as a man for over a decade. So convincingly, in fact, he routinely gained access to areas and institutions that were usually inhabited only by cisgender men.

Garland was born on Dec. 9, 1869 to San Francisco’s first Mexican consul Jose Marcos Mugarrieta and his wife Eliza Alice Garland, whose congressman father had once served on the Louisiana Supreme Court. Jose and Eliza lost two children in infancy, but also successfully provided Garland with two sisters and a brother. From the time he was very young, however, they knew Garland was different from their other children.

Garland’s mother once noted:

She was always a most peculiar, original child and a regular tomboy. The finest doll in the world had no attraction for her if a top or a kite were handy. She delighted in the company of boys; she liked them as playmates and confidents; she developed a dislike for girls in general at an early period of her existence and subsequent events have only served to strengthen that dislike … Being brave and absolutely fearless, she has always been able to take care of herself under any circumstances.

This was certainly true. Throughout his life, Garland had a habit of putting himself in harm’s way to help others. In May 1898, for example, Garland witnessed a runaway horse and buggy galloping directly towards a woman and a girl on the corner of Market and Mason in San Francisco. Garland threw himself at the animal, grabbed its bridle and clung on for dear life until the horse stopped. When it finally did, bystanders erupted into cheers for the brave young man’s actions.

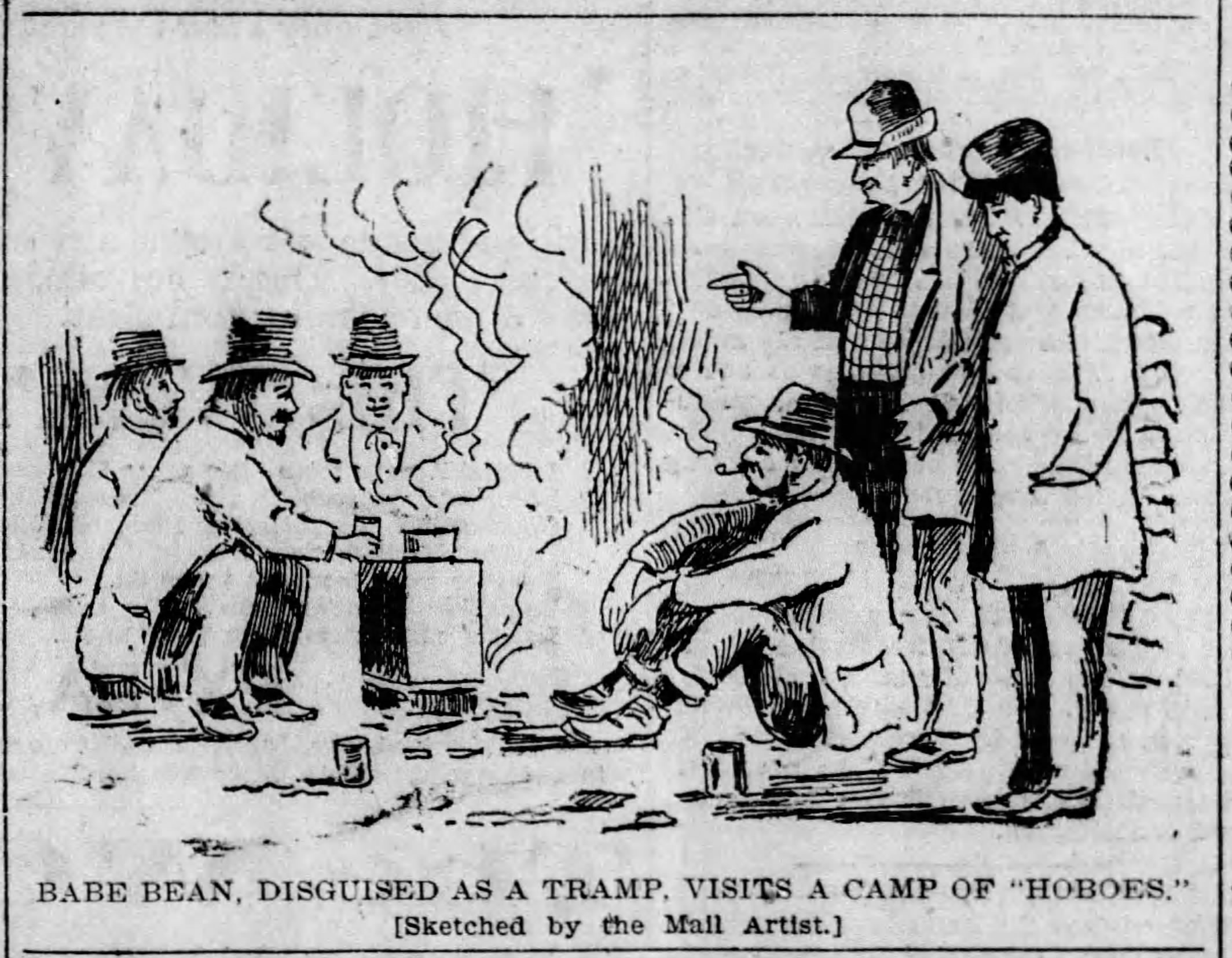

The Stockton newspaper The Evening Mail hired Garland as a journalist that year, when he was 29 years old. He often worked to humanize the most unfortunate members of society. For one story, he went undercover at a homeless camp. For another, he visited Stockton’s State Hospital to report on “life in a madhouse.” In both cases, he wrote about the people he met with sympathy and care. What’s more, Garland’s writing was powerful enough to have a real impact. (After he wrote about the ill effects a gambling den was having on young men, an ordinance was introduced in Stockton prohibiting the playing of keno, a bingo-style game popular with gamblers at the time.)