Once upon a time in this country, you could not come up with a more innocuous title for a documentary than Free for All: The Public Library. The moniker has all the blood-pulsing drama and cloak-and-dagger intrigue of a grade school educational film. The only conceivable title with less pizzazz might be Neither Snow Nor Rain: The Postal Service.

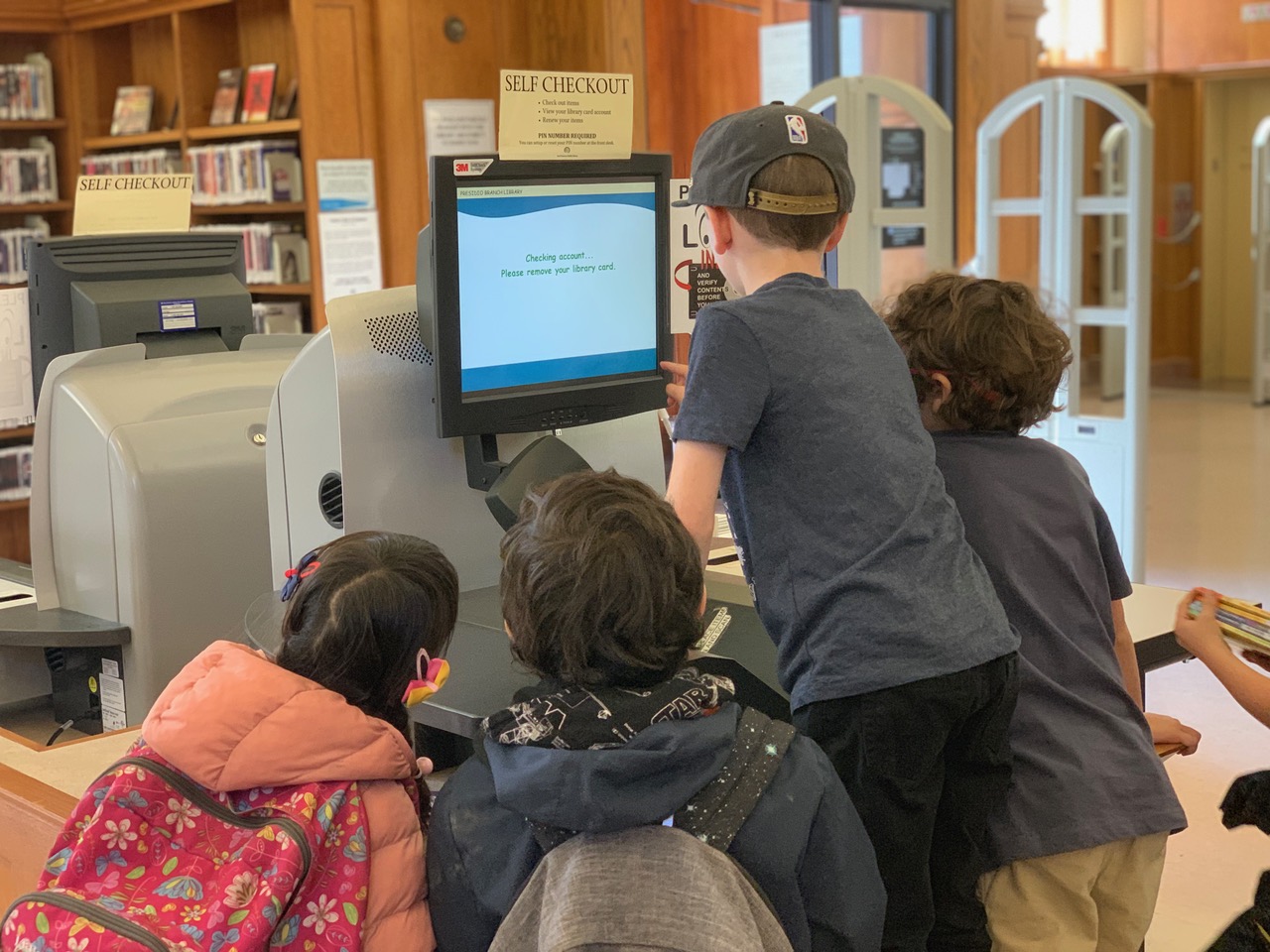

After all, what conflict could engulf the public library? Who could possibly be against America’s most ubiquitous and benevolent institution? The solid brick building where Dr. Seuss and Maurice Sendak live on orderly shelves, where great American novels co-exist with mass-market bestsellers?

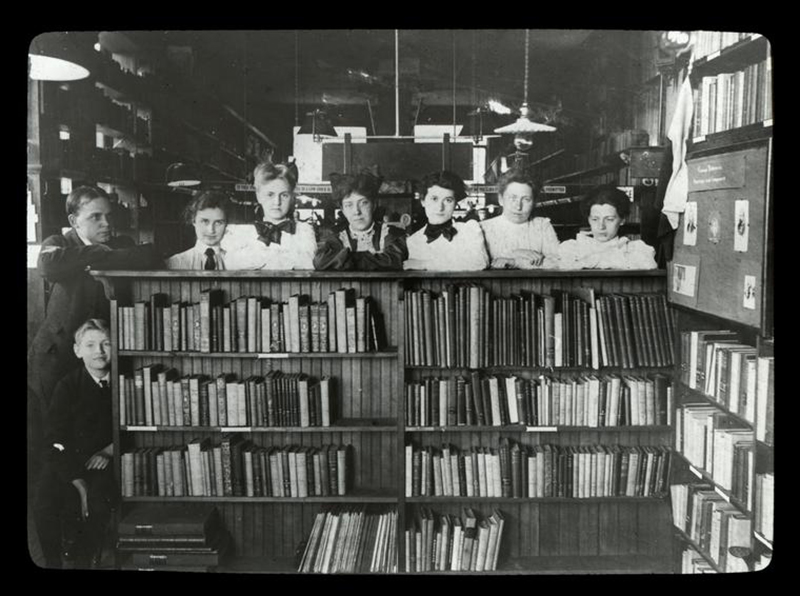

A rangy history and contemporary survey skillfully arranged in a first-person frame, Free for All: The Public Library (airing Tuesday, April 29 on KQED) is both a defense of and argument for the titular institution. Amidst a 150-year parade of pioneering visionaries, community stalwarts and fiercely dedicated branch librarians, Bay Area filmmakers Dawn Logsdon and Lucie Faulknor (Faubourg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans) honor the public library and, along the way, resurface inequities embedded in America’s past.

In the current environment, Free for All feels like an act of advocacy and subversion. Foregrounding the contributions of women and the needs of marginalized groups is antithetical to the current attitude in Washington, D.C. The very fact that the case for libraries needs to be relitigated, and that the country needs a reminder of their essential utility to an enlightened populace, offers insight into how we arrived at the present state of our democracy.

Logsdon and Faulknor (along with co-writer and co-editor Elizabeth Finlayson and co-editor Debra Schaffner) strategically hop between the past and present to excellent effect. The forgotten history of America’s public libraries — a cornerstone of the American tradition of both public good and public spaces, forged by that radical leftist Benjamin Franklin — contrasts sharply with the wave of attacks on public libraries by narrow-minded parents’ groups, short-sighted tax-cutters (California’s Howard Jarvis and Proposition 13 have a cameo), religious conservatives and opportunistic politicians.