In 1964, after Carol Doda danced topless at The Condor for the first time, nightclubs across San Francisco’s North Beach erupted into a topless frenzy. Topless bands, topless clothing stores and even a topless shoe shine all opened in quick succession. But one of the most sensational acts of the time came courtesy of Vicki “Starr” Fernandez, a beautiful transgender woman.

The Transgender Topless Dancer Who Went to War with Prison Authorities

Born in Puerto Rico in 1932, Fernandez ran away to America aged just 14, so that she might live a freer, more authentic life. “As a child,” she told the Bakersfield Californian in 1968, “I was more feminine and pretty than the girls in our school … When I was a teenager, my looks and behavior became an embarrassment to my family. The other kids started making really vicious remarks to me … [In] the States, at least I can dress and act as I please without hurting myself or my family.”

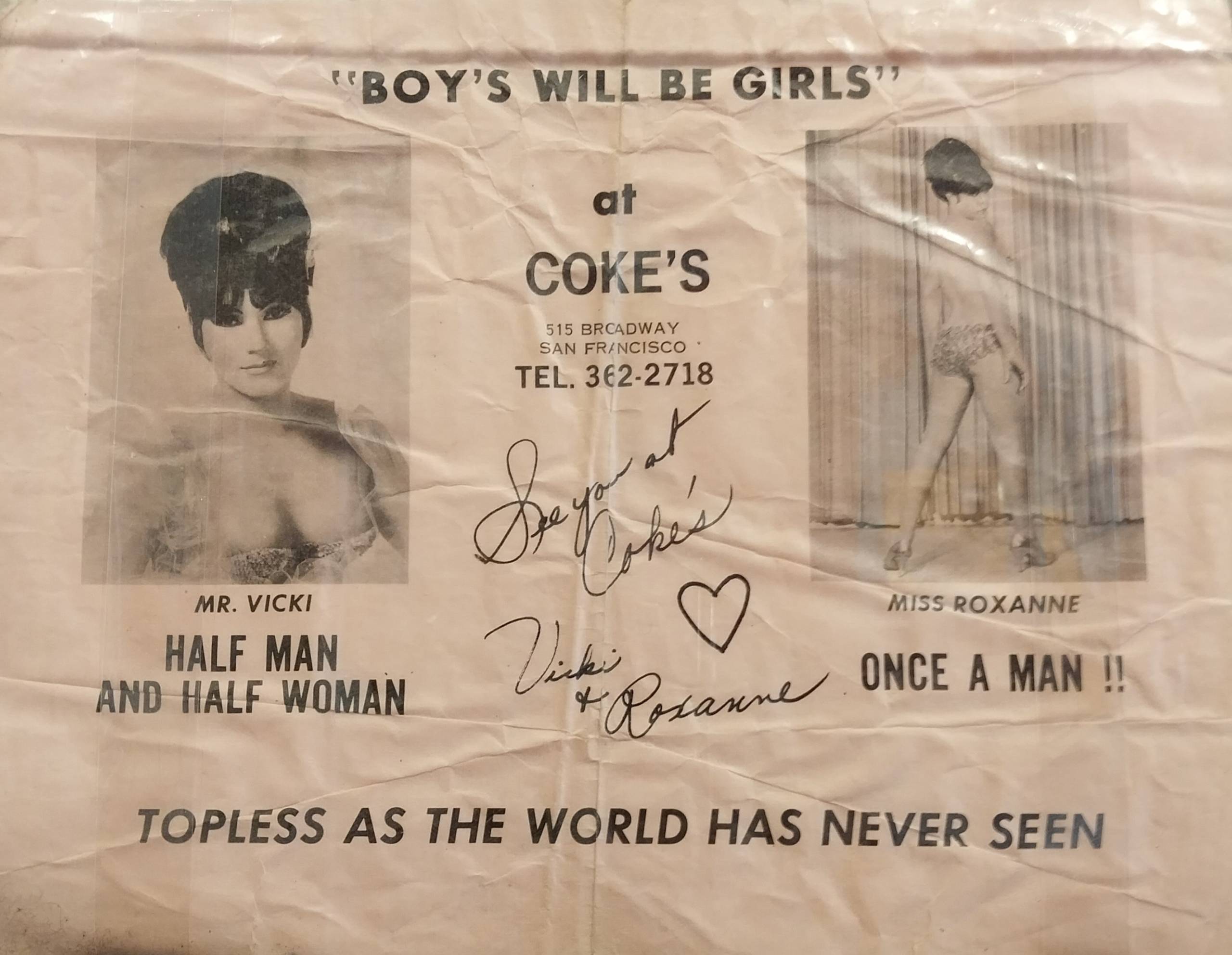

Fernandez danced all over North Beach at clubs including Finnochio’s, El Cid, Pierre’s, Mr. D’s and Coke’s. At the Follies Burlesque, Fernandez participated in the “Battle of the Sexes” — a dance-off in which cis women went head-to-head with trans women and drag queens. (The point was that the audience could rarely tell who was who.) Fernandez was frequently billed as “Mister” (or “Mr.”) Vicki Starr, sensationalizing her trans-ness as a way to maximize audience numbers. This kind of publicity undoubtedly carried major risks for her personal safety and legal standing. Still, she boldly and diligently carried on performing, never shying away from talking about her gender identity.

In 1967, Fernandez told San Francisco Chronicle columnist Merla Zellerbach that she was “working for one reason — to earn money to pay for the conversion operation. As soon as it’s finished, my fiancé and I will get married, possibly adopt children and settle down quietly.” What Fernandez craved, she told the reporter, was “a normal life as a woman.” She was entirely unwilling to give up on that dream, no matter the hurdles in her path. Though Fernandez enjoyed the limelight and relished every opportunity to be her most glamorous self, the nightclubs that made her famous were in many ways merely a means of survival.

Standing up for herself

Fernandez spent much of her life kicking against social and institutional prejudice. From the time she arrived in San Francisco, Fernandez unabashedly lived every moment as the woman that she was. She was a fashionista, always clad in the most elegant styles of the day. She attracted a large, loving and very diverse friend group. She was politically active, keeping files of political pamphlets at home from the likes of George Moscone and Willie Brown, and voting for Harvey Milk when he was a candidate for the Board of Supervisors. Throughout her life, she stood up for and fiercely defended her rights as a woman.

One of the biggest battles of Fernandez’s life started in 1971, when Fernandez’s longterm partner Richard Smith was convicted of homicide and incarcerated. It was far from the domestic bliss she had once envisioned for herself and, making matters worse, she soon found herself restricted from visiting Smith because of her gender identity.

One correspondence from the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo reflects the hostile policies of the era:

Ms. Fernandez remains biologically a male. Accordingly, until such time as a sex change operation is completed, and other approval to visit has been granted, Ms. Fernandez would be expected to enter the institution in male attire and utilize the male rest room.

To Fernandez, these parameters were unacceptable. She quickly sought out the assistance of the San Francisco Neighborhood Legal Assistance Foundation (SFNLAF), and together they went about becoming a thorn in the side of the California Department of Corrections. They started with letters to the California State Prison Solano, in which Smith was originally held, then moved on to the prison in San Luis Obispo, where he was moved in 1974. That year, one letter to its director Raymond Procunier stated:

Ms. Fernandez was allowed to visit [Smith] for a period of 9 months without any questions raised. She made no attempt to hide her identity in this time. It was evidently only after Ms. Fernandez was discovered to be a trans-sexual that her visiting privilege was suddenly denied.

For years, Fernandez and the SFNLAF badgered the Department of Corrections to change their stance on Fernandez’s clothing restrictions. And for years, the Department of Corrections tried to brush them off. Fernandez refused to back down. She began actively studying and campaigning for prison reform. She sought advice from the Prisoner’s Union, the American Civil Liberties Union and the Prison Law Collective. She contacted Rev. Cecil Williams of Glide Memorial, knowing he was outspoken on the topic of prison reform. She befriended Daniel Castro, the senior consultant for the select committee on corrections. She became a relentless force — and eventually, her work paid off.

In 1975, the San Luis Obispo Men’s Colony finally relented and permitted Fernandez to visit Smith in the clothing of her choosing. Access alone was not enough to silence her. When transphobic treatment reared its head in the visitors’ room, Fernandez made sure to document her displeasure in written complaints. One letter from the SFNLAF to H.L. Shaw, then the outside lieutenant of the San Luis Obispo prison, stated:

Ms. Fernandez has been subjected to further abuse which is uncalled for. Her attempts to hold hands and affectionately touch Mr. Smith in the way common between husband and wife has been precluded. Various sergeants under you have offended Ms. Fernandez by carefully policing her hand holding activities.

It never mattered who she was up against, Fernandez was always ready to fight for equal treatment, no matter the venue.

A loving legacy

Though Fernandez’s life was not the easiest, she refused to live meekly or under anyone’s thumb. Proud of her identity, she fought tooth and nail for every scrap of progress she ever made and every shred of happiness she ever found. She was indefatigable when it came to living out loud, no matter who was judging her. But behind closed doors, she was a sensitive and sentimental soul. In the end, it was those traits that formed the foundation of Fernandez’s lasting cultural legacy.

During an era when many of her contemporaries were trying their best to live under the radar and out of sight, Fernandez proudly documented her community in as many ways as she could. In her death, Fernandez left behind a comprehensive goldmine of photographs, flyers and other ephemera that continues to stand as a reflection of the LGBTQ community from the 1950s through the 1980s. These files reflect a joyful and loving community full of beautiful souls who refused to be relegated to the shadows. Now in the care of San Francisco’s GLBT Historical Society, they offer important insight into a woefully under-documented period of time for LGBTQ people.

In 1967, bemoaning the many hardships she faced, Fernandez told the Chronicle: “If I’d been born all girl, none of this would have happened.”

While her life would have undoubtedly been less challenging if that was the case, it was Fernandez’s trans-ness that ultimately made her so special — in her nightclub performances, in her legal battles, and in the keepsakes she ultimately left behind. “You have a very peaceful effect on people,” a friend named Susan wrote to Fernandez in the 1970s. “A harmony that lifts them and can heal them.”

The personal documents Fernandez left behind will continue to do so long into the future.

To learn about other Rebel Girls from Bay Area History, visit the Rebel Girls homepage.

A book celebrating women from the Rebel Girls series, ‘Unsung Heroines: 35 Women Who Changed the Bay Area,’ is available now from City Lights.