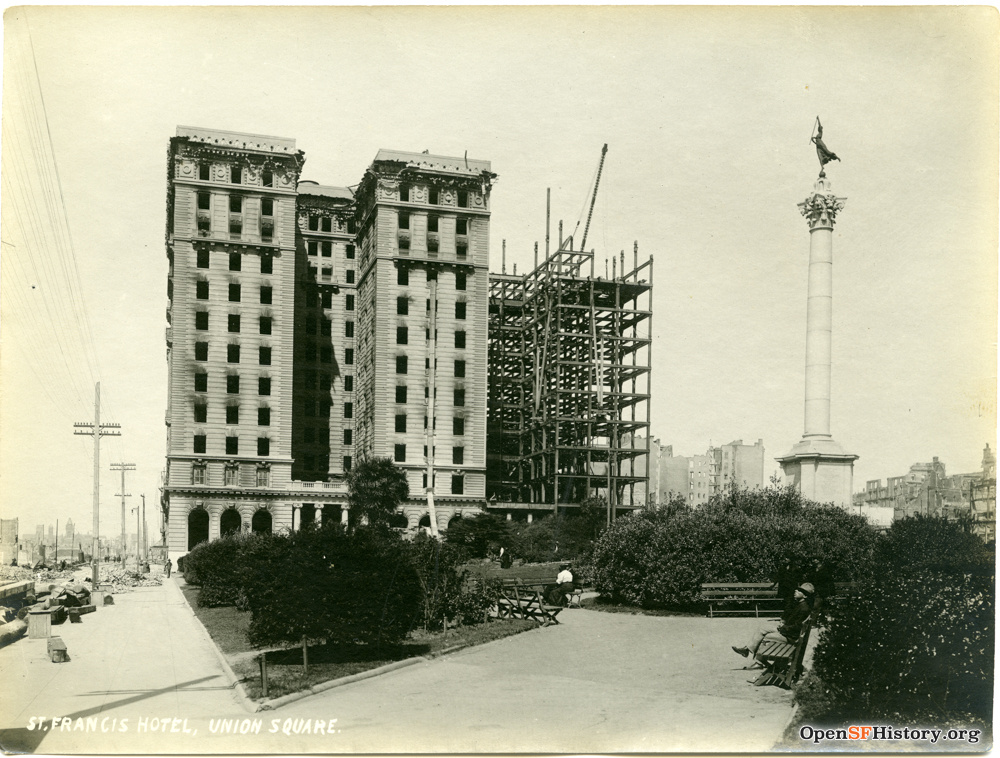

There was nothing low key about the opening of the St. Francis Hotel in March 1904. Built directly overlooking San Francisco’s Union Square, the hotel cost $2.5 million to construct (that’s $87 million in 2024 money) and $400,000 to furnish (nearly $14 million now).

That year, The San Francisco Call and Post raved: “Its construction has been so designed that all the suites are light and airy and its interior domestic arrangements are unrivaled in the West.” The hotel celebrated its opening night with a glitzy party for 600 of the most fashionable people in the city, who spent the evening sipping on Moet & Chandon White Seal champagne.

Since then, the St. Francis has been so married to keeping up appearances that in 1934, it even started washing the coins that passed through its coffers, lest staff and guests get their white gloves sullied. That kind of attention to detail has attracted famous and distinguished guests ever since — including Charlie Chaplin and Queen Elizabeth II. But it hasn’t all been smooth sailing.

Here are five infamous incidents from the St. Francis Hotel’s long history.

The Fatty Arbuckle scandal

Easily the most notorious thing to happen at the St. Francis Hotel transpired on Sept. 5, 1921. During a Labor Day party thrown by movie star Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, a young actress named Virginia Rappe suffered a ruptured bladder and died shortly afterwards. Arbuckle was accused of sexual assault and manslaughter, prompting both the rumor mill and Prohibition-era morality police to kick into high gear. His two first trials resulted in hung juries. Arbuckle was found not guilty after a third round in court, but by then his reputation lay in ruins.

Arbuckle had rented adjoining rooms 1219, 1220 and 1221 on Labor Day and there were people moving between all of them. The enduring mystery around what happened to Rappe in room 1219 was caused by a combination of conflicting accounts from witnesses, two different versions of events from Arbuckle himself (he was married at the time), as well as confusion on the part of a gravely ill Rappe. The most detailed and painstakingly analyzed summary can be found in Greg Merritt’s book, Room 1219. In it, Merritt concludes that Rappe’s bladder injury probably resulted from a combination of preexisting conditions (she lived with chronic cystitis) and an act of intimacy between Arbuckle and Rappe that started consensually.