A

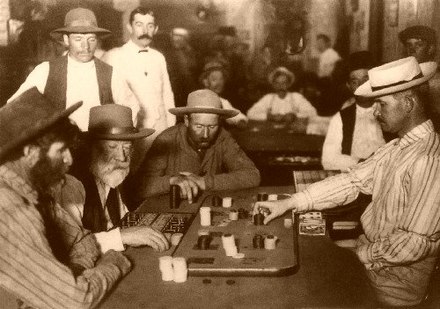

s Eleanor Dumont walked home alone one night after a successful evening of gambling, her path was suddenly blocked by two men. Holding her at gunpoint, the pair demanded she hand over her purse or suffer the consequences. Dumont nodded, maintaining the trademark cool that local gold rush miners knew her for, and reached into her skirt. Rather than pulling out her winnings, she instead retrieved her derringer pistol. She quickly shot the man with the gun, while her other assailant fled in fear. Then Dumont continued her journey home, without a hair out of place.

This was life in the Wild West, and Madame Eleanor Dumont had—by then—learned the hard way how to deal with it.

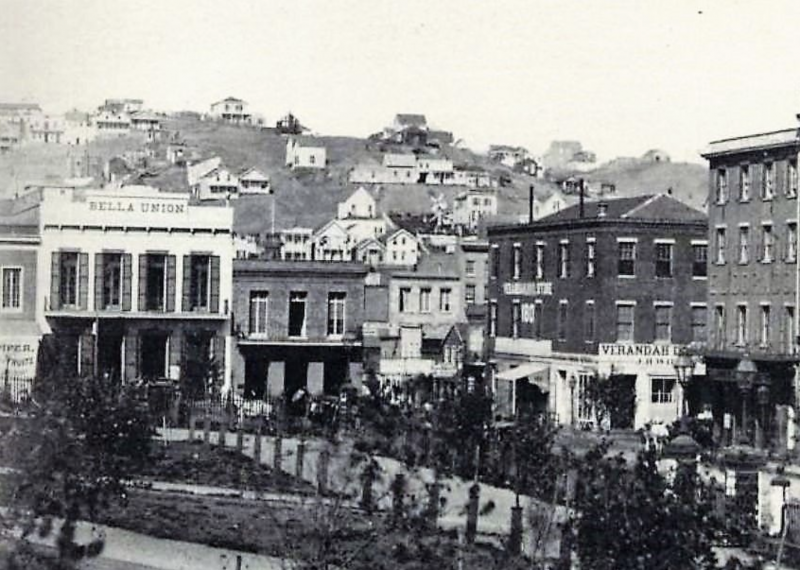

The Frenchwoman—whose real name was Simone Jules—had arrived in San Francisco in 1850, aged 21, and immediately started work as a professional gambler. She was the only woman to deal cards at the Bella Union Hotel (a privilege not afforded to women on the Las Vegas strip until 1971). She was an elegant presence in the Portsmouth Square establishment—always well-dressed and quick to find an easy rapport with the customers. Not only was Dumont enormously skilled with a card deck, she was also an excellent conversationalist. There was never a dull moment at her table.

Despite her popularity, Dumont lost her job at the hotel after she was accused of hustling players. In all likelihood, this was the result of a disgruntled guest who underestimated Dumont’s skill level and resented losing to a woman. Outside of the Bella Union, Dumont had a lifelong reputation for playing a fair game, and handing over winnings graciously when they were due.

Dumont’s firing may also have been influenced by the stereotypes about French women that were pervasive in San Francisco at the time. William Perkins, a Canadian miner and merchant who documented his travels across the United States between 1849 and 1852, once wrote: “French women … are one of the peculiar features of California society. They are to be met with every where, and every where they are the same: money making, unscrupulous, [but] outwardly well-behaved.”