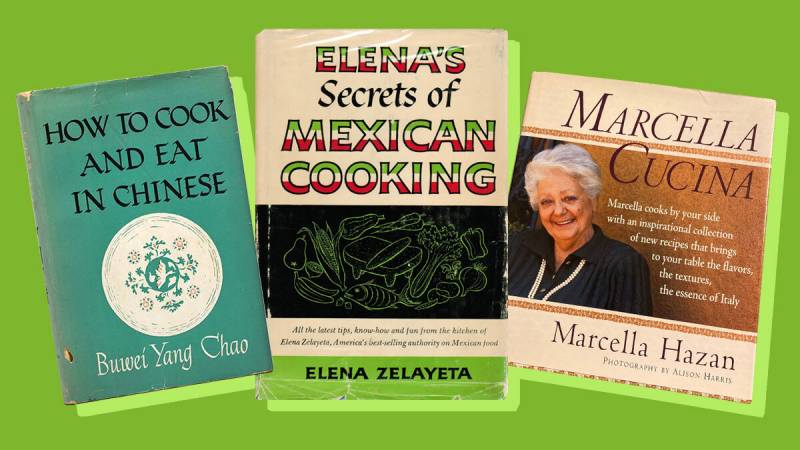

In 1945, an immigrant woman named Chao Yang Buwei published How to Cook and Eat in Chinese, one of the first books to make Chinese food decipherable to American home cooks, coining terms like “stir-fry” in the process. The cookbook was championed by literary figures of her day such as Pearl S. Buck, who asserted that Chao deserved a Nobel Peace Prize for the effort. In her time, she did as much as anyone to help push the cuisine into the American mainstream.

Yet how many Americans know Chao’s name today? How to Cook and Eat in Chinese has long been out of print, and the author herself has largely been forgotten, even among people who write about Chinese food for a living.

Why is it, then, that the record of history is so quick to discard the stories of immigrant women who helped shape the way that America eats? And what can we learn by examining the amazing, sometimes troubling, lives that these women lived?

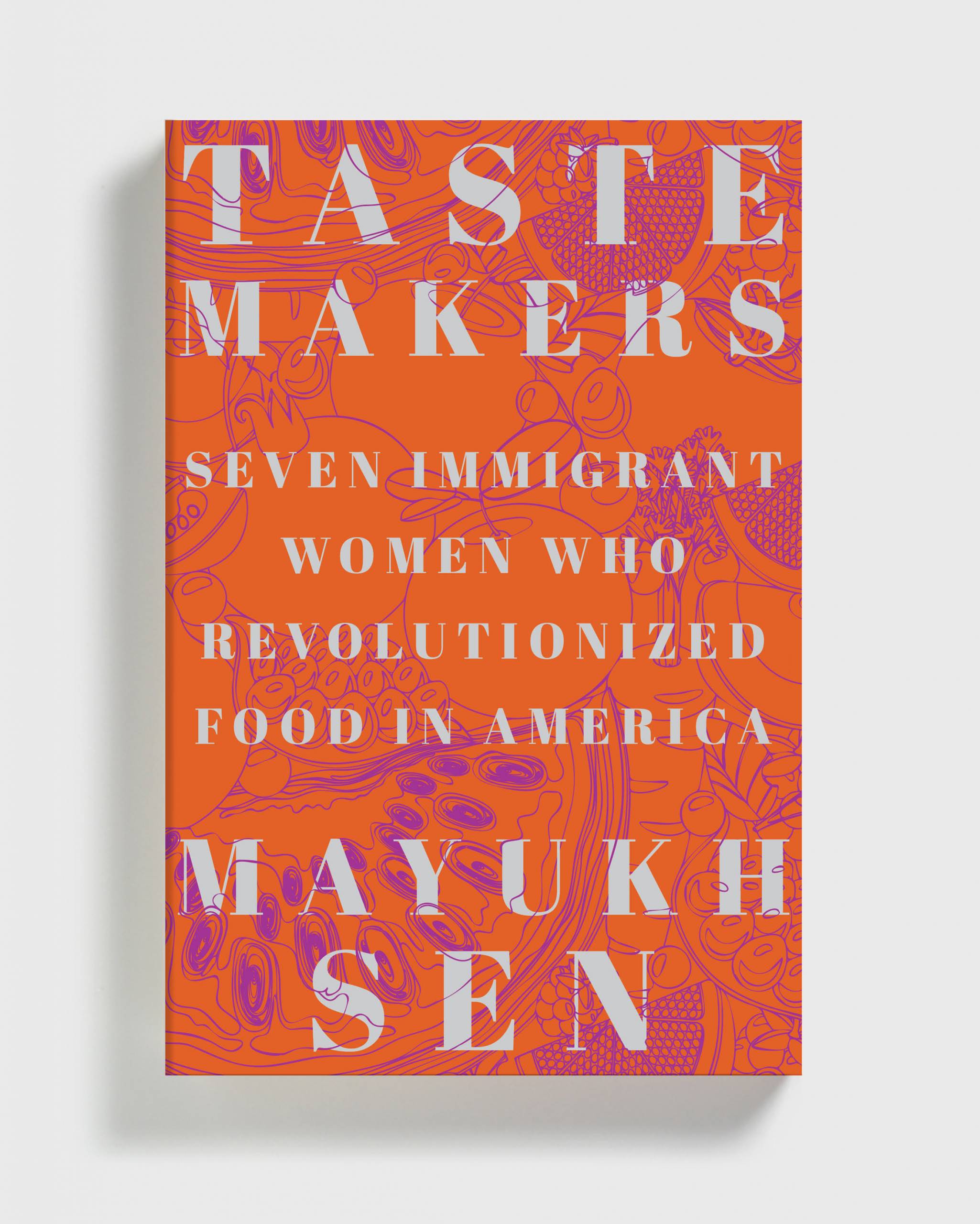

That’s the subject of James Beard Award–winning food writer Mayukh Sen’s new book, Taste Makers: Seven Immigrant Women Who Revolutionized Food in America. So, the book tells the story of Najmieh Khalili, who garnered a reputation as America’s foremost expert on Iranian food despite the fact that no publisher was willing to pick up her books. It profiles France’s Madeleine Kamman, who spent much of her cooking and teaching career in America fighting from under the shadow of the American, Julia Child. And it puts the spotlight on Chao, who experienced erasure even in the pages of her own book: One its striking features is the back-and-forth argument that she has in the footnotes with her linguist husband, who tinkered with the translation of the text—originally written by Chao in Chinese—in ways she hated.

The book also has unexpected Bay Area roots. Two of the seven women that Sen profiles were based in the Bay for a significant part of their lives: Chao lived in Berkeley for the last few decades of her life, and Elena Zelataya—a Mexican immigrant who became one of America’s early celebrity chefs—spent her entire career in San Francisco.