In a news cycle like ours, the closure of McClymonds High School in West Oakland might seem overshadowed by national headlines about the Grand Princess cruise ship, which on Monday carried people with coronavirus to the Port of Oakland.

But the McClymonds story is important. It’s a site where trichloroethylene (TCE), a cancer-causing chemical, was found in the groundwater late last month. And after two and a half weeks away from campus, it’s where students are scheduled to return to next week.

In addition to TCE, the school is surrounded by a horseshoe-shaped freeway structure, thousands of shipping trucks and underground storage tanks– a number of them have resulted in documented leaks. That’s because West Oakland was an industrial bastion for the greater part of the 20th century. Numerous factories, plants and warehouses have sullied its soil. (The city’s only known EPA Superfund Site—a cleanup priority for the EPA— is AMCO Chemical in West Oakland.) It’s home to Alameda County’s highest levels of asthma and lowest life expectancy.

And who lives in West Oakland? During the decades of rampant redlining, it was one of the few places in the Bay Area African Americans could freely move into. That’s why McClymonds, historically, is a predominantly African American school. It’s also known for its legendary alums (Bill Russell and Frank Robinson, to name a few) and honored for its football team recently winning the state championship three times in a row. It’s a pillar of the community, and even with the changing demographics in the neighborhood due to gentrification, the school’s reported population of 372 students is still 80% African American.

Much of the coverage of McClymonds’ closure has centered on input from adults: elected officials, parents and school administrators. But what’s it like to be a student, in a literally toxic environment? I wanted to find out.

Inside the staff room at Ralph J. Bunche Academy in West Oakland, Saba Ghebreyesus (or Ms. Saba as the students call her), director of the youth-led multimedia platform IceeHouse, stood at the dry-erase board writing the agreements for a restorative justice circle. A few minutes later, a handful of students from McClymonds trickled in, followed by a teacher, Mr. Taylor (not to be confused with the McClymonds principal, Jeffrey Taylor, who was also present, as well as Oakland Unified School District Administrator Vanessa Sifuentes-Dimaano).

The goal of the circle at Bunche, where McClymonds students were temporarily relocated, was to give young folks an opportunity to discuss how they’re processing the news that a potentially harmful chemical was discovered under their school just weeks ago.

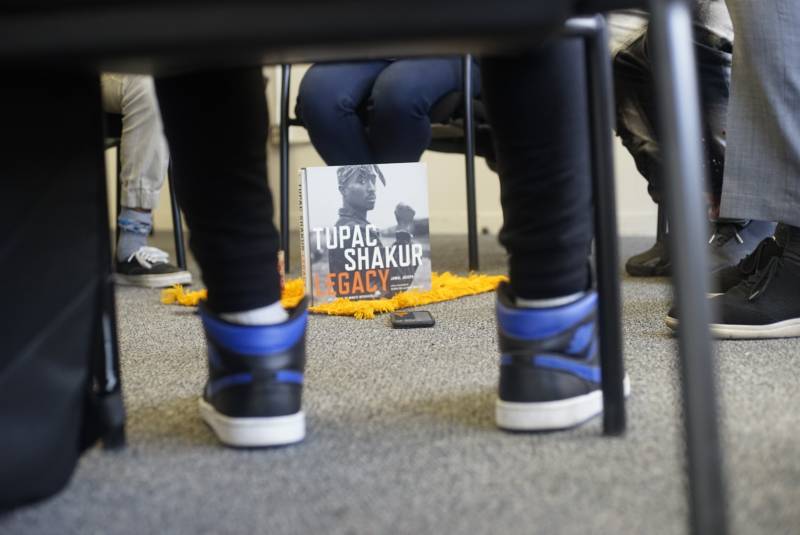

The door closed and the students sat in a circle around a few items: an old sidekick two-way, a brick cellphone, the Tupac Shakur Legacy book by Jamal Joseph, and the talking piece: a miniature statue of people in a rowboat. After some warm-up questions, Ms. Saba asked, “What was running through your mind and what were you feeling when you first heard a hazardous chemical was found at McClymonds?”

“To be honest, I just kinda seen it as no school for us last week,” said a ninth grader named Christopher as he let out a slight laugh.

Miles, a 10th grader, brought up Ramone Sanders, a McClymonds alumnus who was diagnosed with cancer at 19 years old in 2019. “It was kind of like, wow, that could have really been responsible for his death,” he said. “And they could shut down the whole school because of that.”

Other students brought up concerns about how missing class could impact their academic success. “Was that going to affect my credits? Was that going to affect my graduation?” asked a 12th grader named Neyionna. “The TCE, how long has it really been there?… I’m just saying, Mack just needs to be rebuilt, I think, because where Mack is, is an industrial area: the factories, the gas stations… And it’s all black [people], so yeah, I think that’s kinda racist,” she concluded.

A senior named Dwayne pointed out that news of contamination affected his and other students’ mental health. “I have something called generalized anxiety disorder. It gets triggered by events like this,” he said. “I’m a hypochondriac as well. So, I was like, ‘I definitely have cancer.'”

He shared that he’s angry and confused, and that his trust in the adults in charge has been shaken. “If McClymonds were to burn down that day, what would be the plan OUSD would implement for all of this?” he asked. “Is there a plan in place for a natural disaster? It just seems like it took a little too long for us to have a plan.”

Ashely, another senior, said, “It’s really stressful … It’s like: Oh, my god, again? We have ANOTHER issue at McClymonds? It’s just irritating, I don’t want to go through it.” She said moving campuses, dealing with this and ‘senior-itis’ is a lot. “I just want to give up.”

“My initial reaction was to do my research so I don’t make any wrong assumptions about what’s going on,” said Themba, a senior who wants to go to college to become a chemical engineer. “Let me figure out what’s going on, what’s TCE; I don’t want to just hear ‘it’s cancer.’ Let me figure out what it does, what’s the chemical?”

Despite his knack for information gathering, Themba said he didn’t attend any of the community meetings held after the discovery of the chemical “because I knew it was going to be hectic, I knew it was going loud,” he said, adding that he questioned people’s intentions: “Who are you really fighting for? Where do you stand? … Are you really here for the kids who want to learn?”

Ms. Saba received the talking piece from Themba and said, “This is not just about McClymonds, this is about something bigger than McClymonds. This is about years of environmental waste that’s impacting a specific community, when I say years, I’m talking about 30 to 40 years of history.”

(Longer even, I thought to myself.)

Suddenly, a noise outside the door interrupted the discussion. I’m about to slap these little girls in the face, so somebody better go get them right now, said an adult’s voice from the hallway. Where is the principal? … I’m not dealing with this anymore. I done had every emotion this week, and they want to come in here being disrespectful…

Clearly, tensions were high, and even the adults were on edge. Our circle sat quietly as the voice outside passed by.

Principal Taylor briefly stepped out to address the noise, while Ms. Saba broke the silence. “I don’t want ya’ll to get distracted, I want ya’ll to focus on what ya’ll want to share and what’s important to ya’ll. We have one more question before we close out.”

She instructed everyone to take a deep breath. “What do you think needs to be done to make things as right as possible? And what do you need? What do you personally need from your principal and from yourself and from your peers?” asked Ms. Saba.