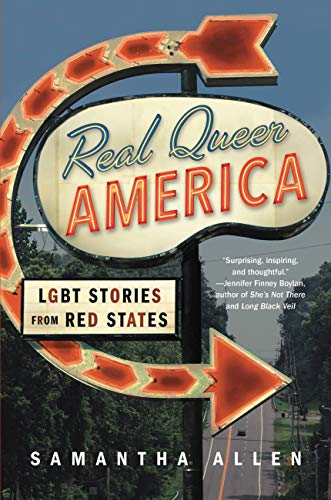

While profiles of the gun-toting, Confederate flag-waving Trump-voter-next-door practically became a literary genre following the 2016 election, journalist Samantha Allen embarked on a mission to demystify what’s actually happening in the heart of the country for her new book, Real Queer America: LGBT Stories From Red States.

A reporter covering LGBTQ+ issues for the Daily Beast, Allen grew up in Southern California and New Jersey, went to college in Utah and came out as a queer, transgender woman during graduate school in Georgia. She knows a thing or two, then, about the way coastal cities are perceived as safe spaces for the LGBTQ+ community while the Midwest and South are stereotyped as universally hostile. When Allen took a cross-country road trip to visit places like Provo, Utah, the Rio Grande Valley in Texas and Johnson City, Tennessee, she was surprised to find burgeoning, tightly knit LGBTQ+ enclaves united by a sense of urgency to fight against their state legislatures’ conservative agendas.

Indeed, recent studies confirm Allen’s observations: according to the Movement Advancement Project, 20 percent of the LGBTQ+ community lives in rural areas, and the majority of same-sex parents reside in those regions as well. Meanwhile, LGBTQ+ people, especially those of color, are increasingly priced out of places like San Francisco, where numerous queer and trans havens have closed in recent years.

Moving to gay-friendly places like the Bay Area, West Hollywood or Brooklyn may no longer be accessible to 18-year-olds from other parts of the country—but it may not need to be, as attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people continue to evolve in their home states.

Real Queer America tells the stories of these demographic shifts through Allen’s conversational travel diary, which is equal parts autobiographical and research-driven, and with heartwarming anecdotes and meticulous citations galore. While Allen—now based in the Seattle area—was in San Francisco during yet another road trip, we met up to chat about Real Queer America and her views on America’s changing landscape.