There is a leap of faith involved in leaving one’s home country, as every immigrant knows—and there is a surge of magical thinking when leaving becomes necessary but the possibilities to leave dwindle.

In Colombia, when that country’s violence lapped at my family’s door and our efforts to leave through official channels dried up, instead of losing hope, my family and I came to believe that if we washed every wall of our house with the intention to prepare it for new owners, then our house would understand we were no longer its dwellers. We had no scheduled meetings with immigration officers, and so we communicated with the plaster and brick of our house, telling it that we were leaving, believing that this would open a door for our exit.

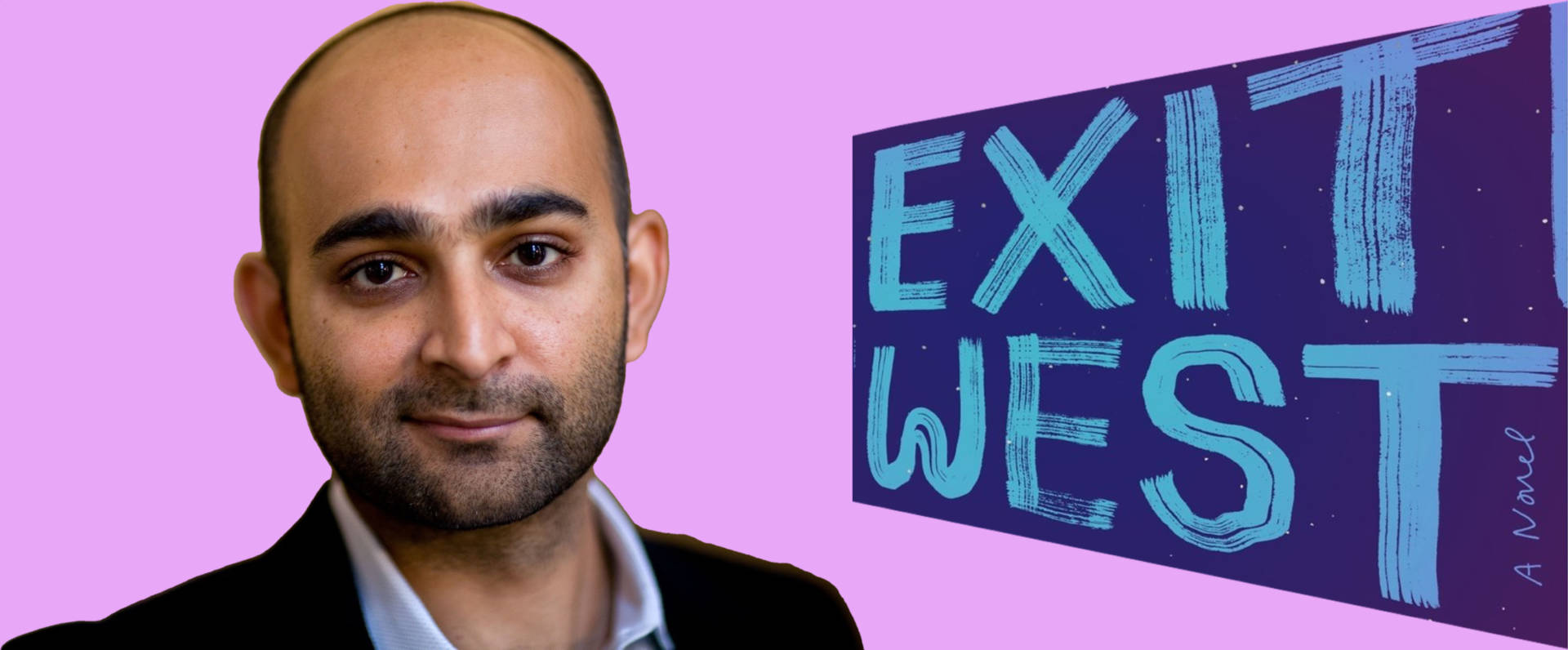

This magical thinking is one of the reasons I love Moshin Hamid’s new novel, Exit West, where—not unlike current events—migrants are unwanted the world over and every continent has its festering of nativist crime.

But in this fictional world, portals appear. Doors that previously led to closets, to bathrooms, to terraces, lead suddenly into foreign countries. Sometimes the doors lead to countries that are better off, sometimes worse off.

At the center of this are two lovers, Nadia and Saeed, citizens of an unnamed country fallen to civil war. As their city loses electricity, as helicopters fly overhead and skirmishes lead to public executions, Nadia and Saeed fall in love. Rumors of portals are met with derision, until the young couple goes through one. They come to a refugee camp in Greece, then find a door that leads into an uninhabited mansion in London that is so filled with small wonders the couple assumes they must be inside an upscale hotel. In what’s perhaps the most memorable writing in the book, Nadia takes a shower:

The heat was superb too, and she turned it up as high as she could stand, the heat going all the way into her bones, chilled from months of outdoor cold, and the bathroom filled up with steam like a forest in the mountains, scented with pine and lavender from the soaps she had found, a kind of heaven, with towels so plush and fine that when she at last emerged she felt like a princess using them, or at least like the daughter of a dictator who was willing to kill without mercy in order for his children to pamper themselves with cotton such as this, to feel this exquisite sensation on their naked stomachs and thighs, towels that felt as if they had never been used before and might never be used again.

Hamid weaves a wondrous web in Exit West pitting extravagance against destitution—thereby forcing an examination of the nature of borders and the hostility toward newcomers. In an interview with Lithub, Hamid expressed his thoughts on the political paralysis in America and Europe toward migrants, saying it stemmed from a denial that mass migration (with climate change and rising sea levels) is likely to be our future, but pointing out that it has also been our past. Exit West seems to ask, is it not human nature to be transient? “For one moment we are pottering about our errands as usual,” Hamid writes, “and the next we are dying, and our eternally impending ending does not put a stop to our transient beginnings and middles until the instant when it does.”