If you have a visible tattoo, you’re probably regularly asked if there’s a meaning behind it. I’ve only managed to sit under the needle once, for an excruciating 20 minutes, but the small Old English “V” on my right shoulder has led to a lifetime of questions. “What is that?” people ask, and I’m forced to come up with a pithy story about what was, honestly, a spontaneous, hazily thought-out decision.

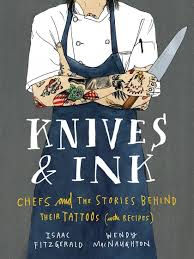

Knives & Ink: Chefs and the Stories Behind Their Tattoos (Bloomsbury; 2016) is the latest collaboration from Isaac Fitzgerald, editor of Buzzfeed Books and former editor of The Rumpus, and Wendy MacNaughton, the San Francisco-based illustrator and author of the quixotically beautiful Meanwhile in San Francisco: The City in Its Own Words. Their 2014 collaboration Pen & Ink explored the stories behind the tattoos of a spectrum of people, famous and ordinary. For this sequel, it’s no surprise Fitzgerald (who has 12 tattoos) and MacNaughton have shifted their focus to chefs. It’s apparently a requirement for chefs these days to get sleeve tattoos on the first day of work; spotting a tattoo-less chef competing on Top Chef is like finding a feminist Mexican immigrant at a Trump rally. Fitzgerald mentions as much in the introduction to Knives & Ink (just after confessing to being a terrible cook—I can relate):

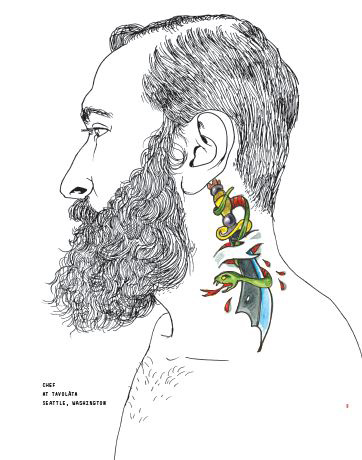

What is it about chefs and tattoos? Whether you’re looking in a backwoods diner or a Michelin-starred eatery, it’s hard to find a cook who doesn’t sport some ink. A lot of chefs get a tattoo because they see it as a commitment to the craft. A neck tattoo or a hand tattoo – or maybe even a tattoo atop your head – is a way of ensuring you’ll never work a desk job again. Others get tattoos for the reasons so many of us get them, to remember a moment, or a person, to carry something with us for the rest of our lives. Still others get them for possibly the best reason of all: just for kicks. Wendy MacNaughton and I have attempted to portray these tattoos, some food-related and some not, as the beautiful works of art they are, and to share the fascinating personal stories behind them.

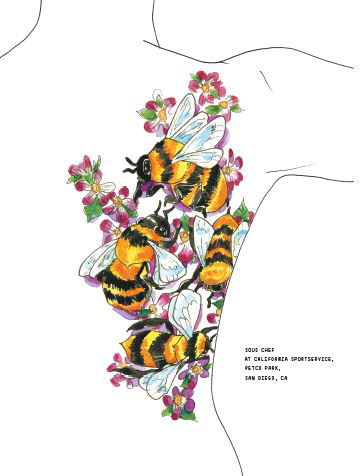

For the most part, the stories and anecdotes collected in the book are intriguing. Each page contains lovely black-and-white drawings of body parts, with the actual tattoos rendered by MacNaughton in full-color and fine detail. Some of the stories are short: “They’re just pretty,” says Sean Thomas, Chef De Cuisine at Blue Plate in San Francisco, about his pink daisy-like sleeve tattoos. Others are heart-breaking in their intimacy. Take the story about the angel wings on the forearms of Danny Bowien, owner and chef at Mission Chinese Food.

My mother was super religious and collected angel figurines. She was sick most of my childhood and passed away when I was in high school. At the age of twenty I moved from Oklahoma City, where tattoos were illegal, to San Francisco. I got these wings in a tattoo shop in the Castro. They were expensive and I was broke, so I had to get them one at a time, about a year apart. They were, and still are, my way of always keeping her with me.

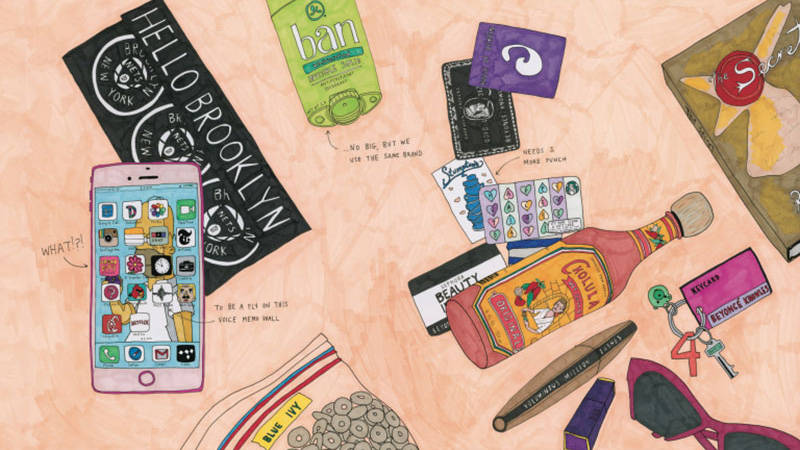

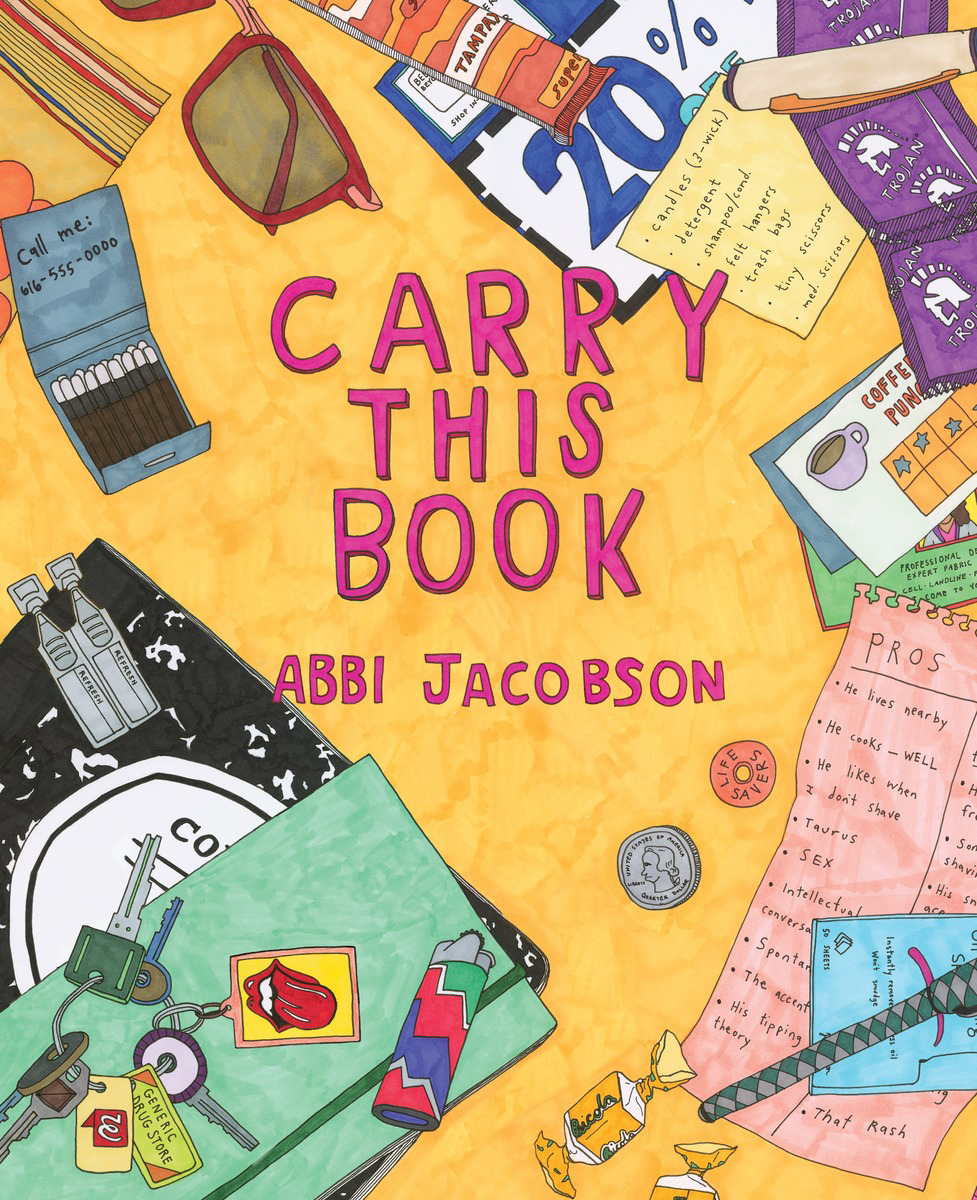

Tattoos are a way to preserve a moment, a child, a lost parent, a spiritual understanding, a location, whatever it may be, with us always. Of course, you don’t necessarily have to subject your body to a hot needle to carry hope, meaning, and the mundane through life. Which leads me to Abbi Jacobson’s new colorful illustrated romp Carry This Book (Viking; 2016). Fans of the Comedy Central show Broad City will recognize Jacobson as one half of the bawdy, brilliant, feminist version of Cheech and Chong; it turns out that she’s also a talented illustrator, with two coloring books and a degree in Fine Arts under her belt.

Like tattoos, the items people carry around with them in purses and pockets can also reveal character, desire, hopes, dreams. Carry This Book is chock-full of adorable, full-color marker and pencil drawings depicting what Jacobson imagines to be in the pocketbooks and purses of those both famous and fictional. “This book is my own sort of fan fiction — full of objects I think make people refreshingly interesting or refreshingly normal,” writes Jacobson.