We live in a world savaged by disbelief, where we’re quick to label everything a scam. So one of the strangest effects of Tom Sachs’ Space Program: Europa — both the multimedia art installation showing at San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA) through Sunday, Jan. 15, and the six-hour performance that Sachs and company undertook for the show’s opening weekend — is how it reconstitutes the possibilities of belief.

That it does so by constructing artifacts of a mission to Europa, Jupiter’s icy moon, as a Smithsonian style exhibition, and then re-animating that exhibition through performance, is kind of miracle. No matter how you experience Sachs’ wildly inventive take on exploration, either by roaming through the YBCA galleries or catching all or part of the accompanying performance (which the artist and his team intend to remount once again before the show closes) the message is bracing and consistent: we are creatures of belief and imagination. And these qualities compel us — sometimes vainly and foolishly, but always with joy — to wilder and wilder feats of daring.

Stand before “Mission Control Center” in Gallery Two and marvel at its “can do” futurism. Comprised of 50 television screens, a JVC boom box, and a ticking clock, it’s all you need to feel like you’re witnessing the longest human voyage in history. The same goes for the Hibachi grill in the YBCA’s bamboo garden that plays such a crucial role in piercing Europa’s icy surface (a piece in the exhibit that gives new meaning to ice sculpture); and for that matter, the majestic “Landing Excursion Module” in Gallery One, an eye-catching plywood variant on the Apollo 13 lunar module measuring over 20 feet in height and width. The line between art and equipment has never been so thin. It’s a boy scout’s path to the sublime.

To see Sachs and a company of at least 20 helpers, including Myth Busters’ star Adam Savage, turn the exhibition into a performance is thrilling. Sachs prefers to call it a “demonstration”, but that word undersells the sweeping power of what he’s achieved. Space Program: Europa has the feel of a distant memory coming to life. If the exhibition is the proof, the aftermath of one grand moment in human history, the performance of Sachs’ demonstration is the ghostly reminder of what it took to make it happen.

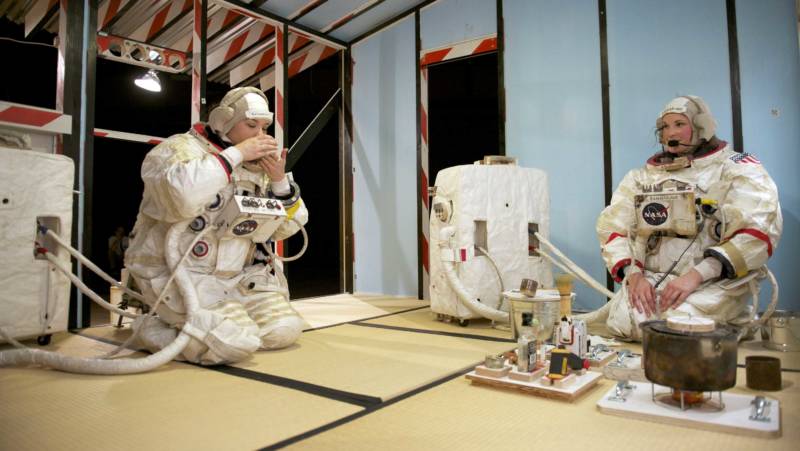

So when we enter the main performance space in Gallery Two, we’re in Mission Control just before the first manned (though both astronauts are women) flight to Europa. Three technical operators sit at the master panel, readying for blast off. Sachs paces the stage, confident and nervous. Of course, it’s all a ritual of performance: From Capricorn 1 to Apollo 13, the space drama has always been the stuffy cousin to the backstage farce.

If we have lost a taste for the momentous nature of space flight, Sachs reminds us how wonderful and challenging the momentous can be, even if just a stunt. So in the quiet right before the start of the mission, the first movement of Gustav Holst’s The Planets, “Mars, the Bringer of Wars,” roars through the speakers. And we watch on the monitors as the astronauts — in full space suit regalia — jog through the YBCA galleries towards their ship. The museum erupts into applause, the first of many spontaneous expressions of joy throughout the performance.