Sick of getting your view blocked at live shows by people holding up their phones? Apple was granted a patent yesterday for technology that can disable those cameras — at least in specific places.

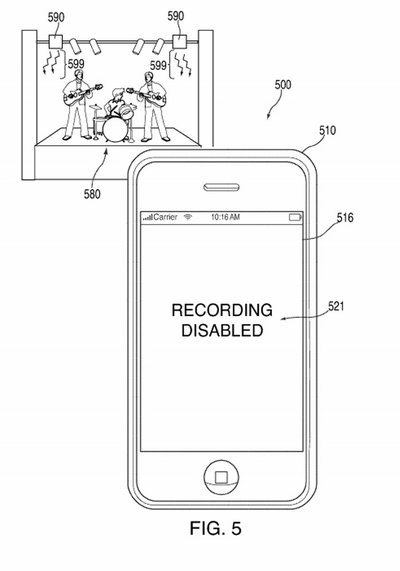

The system mapped out in this patent would use infrared emitters to temporarily deactivate the photo and video capabilities on devices like mobile phones, laptops, stand-alone video or still cameras or any other “electronic device with an image sensor.” Venues, or those in charge of a given space, could post an infrared emitter to temporarily, and remotely, disable those recording functions on devices within the emission range.

Within its patent application, Apple specifically laid out the technology’s use in the context of musicians and a live concert venue.

There are many ways in which the raw technology could make its way into the marketplace, but it’s easy to imagine how the technology, by itself, could be used to limit free expression. For instance, blockers could be installed in public spaces or in other places where visitors may want to snap a picture or record video. That could give governments, the military or police an easy means to shut down activists. On a less grave note, it could also be a vehicle for certain organizations — museums, for example — to maximize sales of their images, by preventing visitors from simply snapping their own.

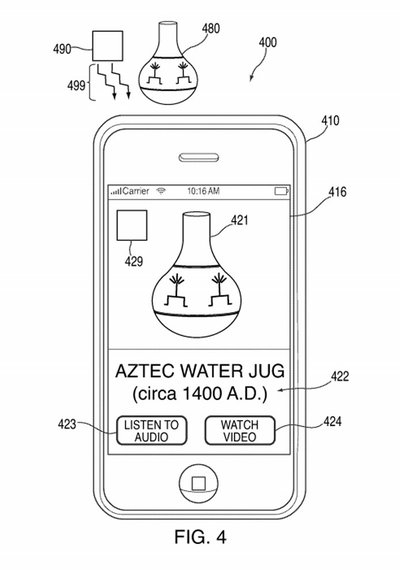

It’s not all ominous, however. Another potential use detailed in the Apple patent lays out how this technology could provide a multimedia-rich experience to a user, in much the same way that a QR code on a commercial product works: Metadata could deliver detailed descriptions, hyperlinks, video and audio narratives and other materials to the person using the phone. (Unlike artists at a concert or actors on a screen, however, an object like the “Aztec water jug” used as the example in Apple’s patent could never claim royalties or other payments.)

But it’s a sign of the times that stakeholders like movie distributors and theaters, concert venues, presenting organizations and record companies, along with musicians, may increasingly look to technology to enact policy, rather than work out the issues by legal or social contracts with the public.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))