I’ve spent most of my life resenting the one percent — specifically, those living off the fruits of vast family inheritance, hedge funds, and other less industrious and sometimes nefarious methods of gaining wealth. If that offends, I’m not sorry. You could blame it on my communist father. You could blame it on jealousy. You could blame it on a stiff dose of working-class pride. All of the above would be true.

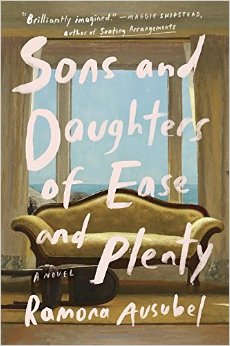

Or, you could blame it on intellectual laziness; the fact that I’m convinced the rich live and breathe in a totally different stratosphere, clueless to the concerns of those of us closer to the bottom of the income gap. Yet after reading Ramona Ausubel’s new novel Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty, I’m forced to reconsider my position. Like all great fiction, Ausubel’s story of a once-wealthy couple’s plunge into poverty has gifted me with empathy toward characters I would likely disdain in real life.

I’m not sure if Ausubel, who lives in the Bay Area, was raised in a wealthy family herself. (In this interview, she hints that her family was once wealthy but lost their money.) Whatever her background, she has a stealthy insight into the complicated nature of judgements around money and class, and the easy generalizations inherent therein. In the same interview, Ausubel addresses how wealth and poverty too easily become “weird, mythic realms” where real people are flattened by that which is projected onto them:

But that difficulty, that fear, ended up being a big driver for me while writing Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty. Does being impoverished make us more valuable emotionally? Are we allowed only one at a time, material wealth or emotional wealth? That seems problematic for lots of reasons. How rich does a person have to be to cease to deserve empathy? This disconnection is dehumanizing, and it turns both wealth and poverty into these weird, mythic realms.

Sons and Daughters of Ease and Plenty tells the story of Fern, Edgar, and their respective families. Married with three children, they live in New England; both were born rich. Neither has had to work, in the truest sense, though Edgar spends years writing a loosely disguised autobiographical novel about a son who disavows his industrialist father’s legacy. The novel’s opening sentences are a perfect introduction to the ease and plenty that surrounds the family.

Summer fattened everybody up. The family buttered without reserve; pie seemed to be everywhere.

With one phone call, everything changes. It turns out that Fern’s family money — the wealth that paid for the summer house, the fine house back home, the expensive Swedish furniture — it’s all gone, given away to various charities by Fern’s migraine-plagued father at the end of his life. There is a Plan B, though: Edgar could return, chastened, to his father, and ask to take the helm at Keating Steel, the very destiny he’s spent his life running from (but not running fast enough to prevent him from accepting gifts of money and material items from his parents).