Opening the door to The Grace Jones Project at the Museum of the Africa Diaspora is like entering the shrine of a living goddess.

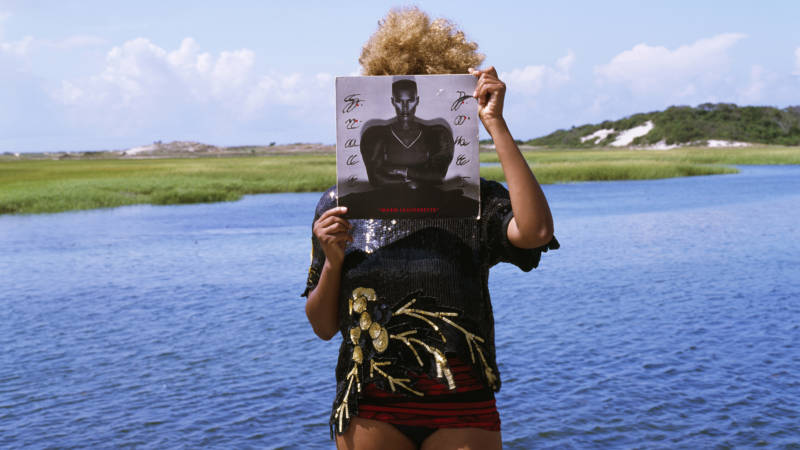

In the center of the gallery two display walls separate the space, drawing a line through the exhibit. On one side of the line, the artist represented is Jones herself. Thirty-two evenly arranged Grace Jones records are divided and mounted on black backgrounds. The singer, actress and model features prominently on almost every album cover. Her aura, and her shifting series of identities, dominate the room. The effect is that of a pop star’s power to dazzle.

In the center of the gallery two display walls separate the space, drawing a line through the exhibit. On one side of the line, the artist represented is Jones herself. Thirty-two evenly arranged Grace Jones records are divided and mounted on black backgrounds. The singer, actress and model features prominently on almost every album cover. Her aura, and her shifting series of identities, dominate the room. The effect is that of a pop star’s power to dazzle.

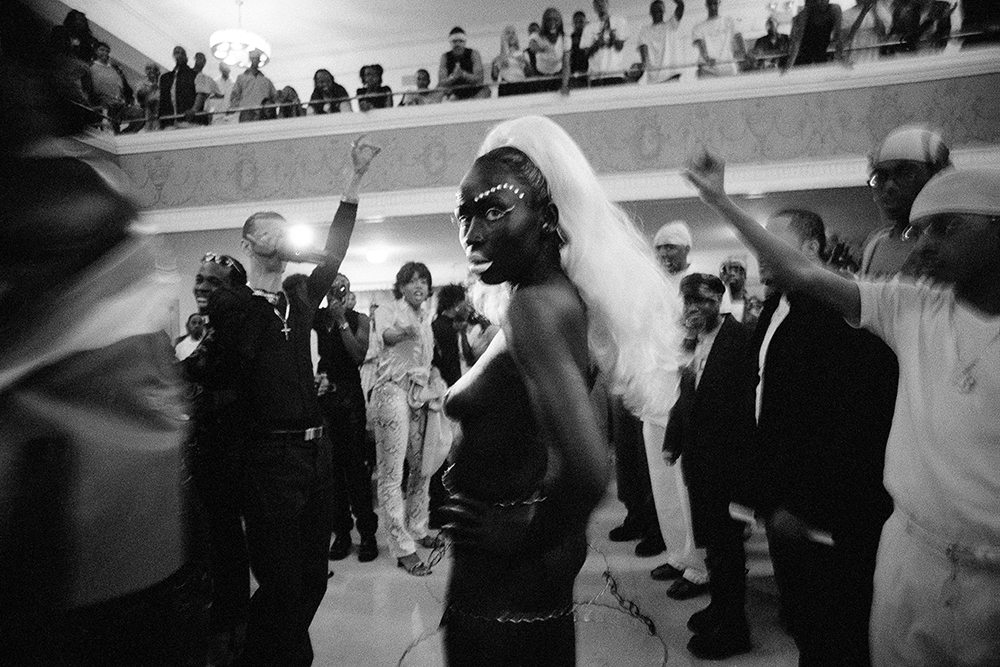

A reel of Jones’ music videos loops alongside the wall of albums. The projected images shriek with the 1980s MTV era of self-conscious experimentalism. Jones and her collaborators capitalized on the fact that the camera loved to look at her. But she knew how to look back. Jones stared down the male gaze and smashed it to bits. Sunglasses, costumes, hats, cowls, even her makeup were all parts of the armory, to be removed only at her behest.

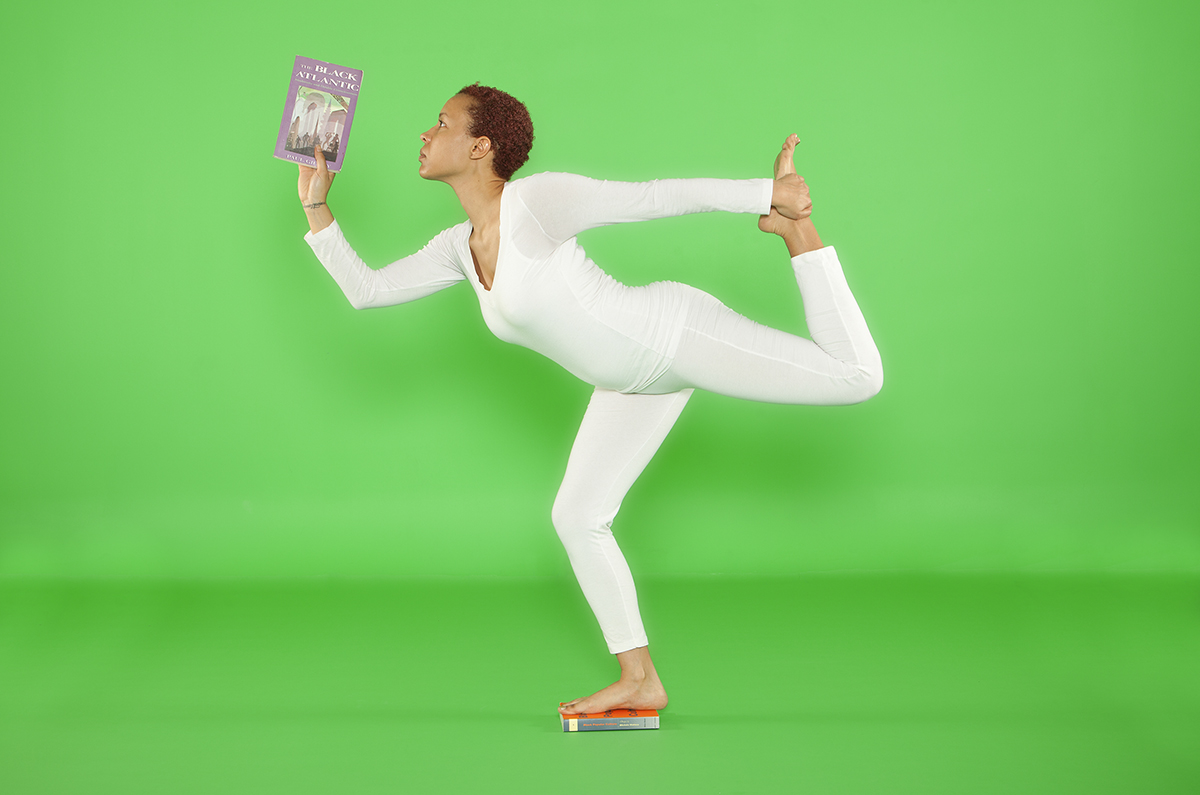

The other side of gallery space contends with her enduring cultural influence and its impact on musicians and artists, pop and otherwise. Harold Offeh, a London-based performance and video artist, filmed a live action version of himself attempting the famous arabesque pose from the cover of Jones’ 1985 album Island Life.

Unlike Jones, Offeh is nude as he stands with his limbs outstretched (Jones’ body is selectively wrapped: an ankle, a wrist, her breasts). His round stomach lacks her body’s sculptural ideal, and he’s all the more human for it. After holding something like her pose for a minute, he loses his balance, utters a sigh, and the film begins again. It’s a witty piece that exposes the album cover for what it is: a cut and paste technique — a pre-Photoshop illusion — by the photographer Jean-Paul Goude.