SF Playhouse’s production of Andrew Hinderaker’s Colossal takes the sports melodrama into aesthetic and philosophical territory that one never would have imagined possible. And like most truly innovative art, you forgive its weaknesses and embrace its strengths. When the soul is right, every sin is minor.

Colossal is a stew of melodramatic clichés — Oedipal conflict, devastating injury, concerned therapist, gay romance (secret, tortured, and ecstatic), drum lines, militaristic coach, homoerotic locker room, homophobic teammates, and modern dance as spiritual practice. None of it should work, and yet like Greek tragedy — of which this play is a peculiarly American variant — Hinderaker spins the hackneyed tropes in a way that makes the well-worn seem new again.

The story is simple: Mike — talented, gay, and performing in his father’s modern dance troupe, becomes a first class Division 1 Football player. He’s bona fide NFL material. Mike loves football, especially for the bravado, the camaraderie, and the sheer brutality of taking a hit. When he suffers a spinal chord injury in his senior year, his world falls apart. Hinderaker gives us two Mikes, played by two actors: the injured one of the present (Jason Stojanovski), and the brash athlete he once was (Thomas Gorrebeeck). When Mike and Mike go at it the effect is electric, and the acting between Stojanovski and Gorrebeeck is savage.

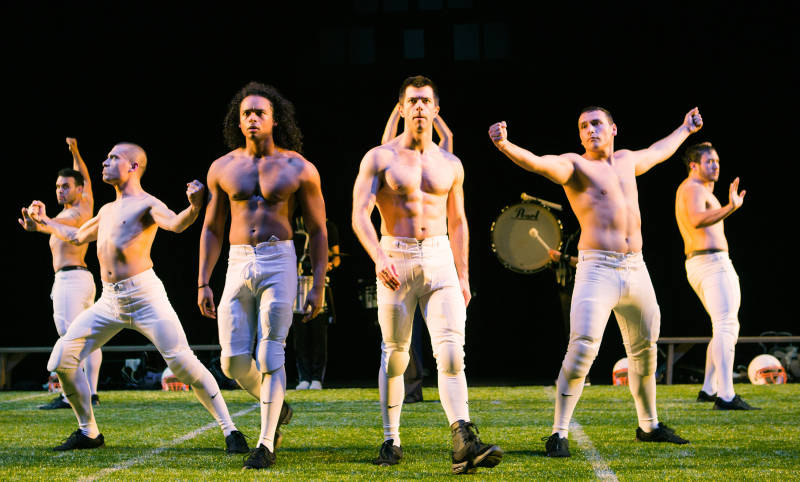

It is this formal invention that makes Colossal soar. Hinderaker, with a great deal of help from Jon Tracy’s sharp direction, creates a context from which melodrama can slip into myth. As we enter the theater, a drum line pounds away in war-like preparation for what we’re about to see and a scoreboard counts down to curtain time. A black scrim at the back of the stage creates a sense of endless depth as the drama unfolds, making the action appear to take place both in time and out of it. Also, the actors are plausible athletes, so watching them work out feels as if you just happened by a practice, instead of going to the theater.

It’s a pleasure to see a piece of theater so acutely aware of the dynamics of perception. Too many playwrights take the relationship between play and audience for granted. Hinderaker establishes a context for everything that happens and so even the most pedestrian scenes take on a mythic importance. A weight training challenge has the aura of a boisterous game among the gods. Sex isn’t desire, but instead a tempting of fate. A father’s disapproval comes in the form of a dream ballet, performed as a halftime show in the middle of the play and the ballgame.