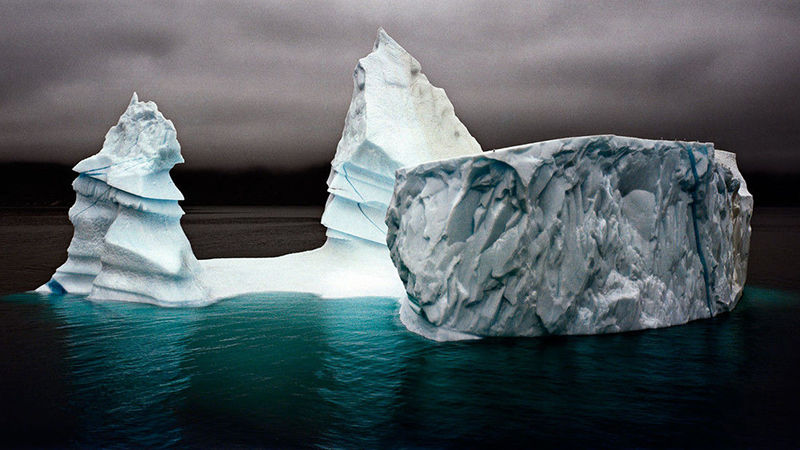

Seaman had no idea she was embarking on a 16-year love affair with the Arctic, and then the Antarctic, too. “There are no two icebergs alike,” Seaman says. “They have their own unique personalities. Some do kind of glow like that. Others are like ‘Eeeeeh. Don’t look at me! I’m having a bad ice day!’ They have so much personality.”

Hear more about Seaman’s Adventures on Ice.

Seaman’s photos of icebergs are spectacular, jaw-dropping meditations in shades of blue and gray. The ice often looks lit from within, beckoning the viewer to step inside the photograph. The artist obtained access to parts of the world most people don’t go by traveling with polar expeditions, photographing penguins, icebergs, and over time, climate change, along the way.

“There’s no place for apathy anymore,” Seaman says, her voice trembling with emotion. What started on a whim for the artist became a passion, and then a cause. “I think for too long we’ve allowed ourselves as citizens of this planet to think that it’s a right to be able to do what we want to it.”

Seaman’s photo “Grand Pinnacle,” is just one of the striking pieces in Vanishing Ice, a traveling exhibition from Washington State that covers more than 200 years of artistic engagement with Arctic and alpine landscapes.

The curator, Dr. Barbara Matilsky of the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Washington, has spent a lot of her career thinking about the way artists like Seaman have followed the work of scientists and popularized their research, “getting people to appreciate the beauty and majesty of these regions,” as she puts it, “so that they would be inspired to protect them.”

The original exhibition, featuring 80 works from artists all over the world, premiered at the Whatcom Museum in March 2014, and has continued on to The El Paso Museum of Art and the McMicael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario.

As with Seaman’s body of work, Vanishing Ice also serves as a record of climate change over the centuries, showing audiences what the world looked like even before cameras came along. “It’s an ‘a ha!’ moment when you see these works,” Matilsky says, “because it becomes very clear that this is just not these sporadic events happening here and there, but the actual results of this climatic phenomenon.”

The David Brower Center in Berkeley is presenting an abbreviated version of the exhibition, featuring around 25 works. But the venue is also hosting a series of related events, like a talk with Matilsky in February, and an evening of music with Other Minds in May, featuring San Francisco composer Cheryl Leonard.

Leonard has written several pieces using natural objects found in polar regions that will be performed at the concert . In Melt Water, her instruments are icicles, hung so as to drip into scientific glass ware.

Like Seaman, Leonard sees her work as a form of documentation, as well as art. “The sonic landscape in these places will change and perhaps these sounds will become extinct,” Leonard says.

Stanford University Professor Jon Krosnick, who’s studied American attitudes about climate change for two decades, believes that Americans are really starting to understand the impact of global warming.

“We’re used to seeing the country split 50-50 on many issues,” Krosnick says. “In about 25 surveys, conducted over two decades, most people believe the earth has been growing warmer over the last century. Between about 75 and 80 percent of Americans say they believe that’s probably been happening.”

Museum curators reflect this shift in awareness, in part, reflecting the interest of artists they build shows around. It’s hard to spit without hitting an exhibition that touches on climate change. Some, like the one at 1337 Gallery in San Rafael, are simply called Climate Change. Others, like The Idea of North, just finished at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, broadly hint at the subject.

Can these public conversations move people to take meaningful action? Krosnick is optimistic in this regard. “The world’s most important photographs are typically pictures that powerfully communicate the agony of people far away from us in a way that makes it human,” Krosnick says. “That highlights the potential for artists to activate our emotions in ways that make a real difference in how we think about very concrete, very everyday issues.”

More Icebergs, Including One That Rolls