After “re-imagining” their galleries, the Museum of the African Diaspora (MoAD) reopened yesterday with three solo exhibitions, featuring artists Tim Roseborough, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle and Alison Saar. On a material basis, the trio’s work couldn’t be more different — from digital prints to rough-hewn figurative sculpture — but connective themes between the shows enrich each in turn, bridging generations, conceptual approaches and subject matter.

On the second floor, Roseborough’s small installation is the first of two “Emerging Artists” exhibitions selected by MoAD from a pool of nearly 50 applications. Proposals from local artists addressed the institution’s thematic lodestars: origins, movement, adaptation and transformation (helpfully arranged in large vinyl letters near the lobby ceiling). Roseborough’s exhibition Four Themes translates all four — literally — into a glyph-like alphabet of his own making.

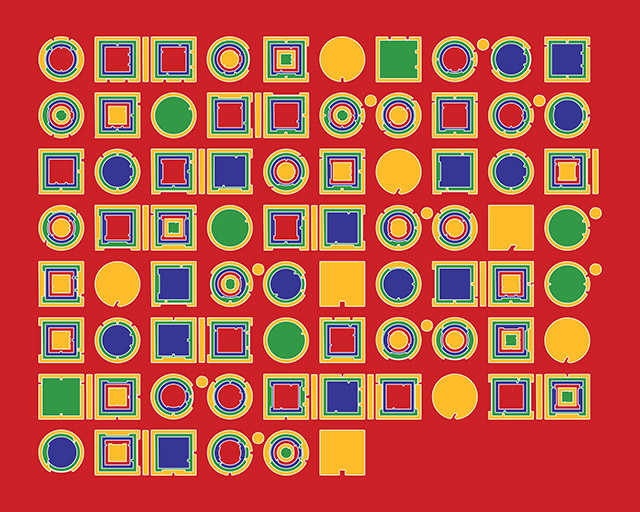

Englyph (“English” plus “hieroglyphics”) nestles square and circular shapes of vibrant primary colors within one another, rendering the words “Life began in Africa” in a symbology that looks like a cross between Maya and sci-fi lettering systems.

Roseborough’s crisp digital prints accompany a video also titled Four Themes, which animates and gives a robotic voice to Englyph, each “word” bouncing like an indecipherable sing-along song when spoken. The banal, institutional language of MoAD’s mission statement becomes otherworldly and strangely mesmerizing, a great segue into the adjoining gallery’s display of Who Among Us…, Hinkle’s exhibition of drawings, collage, “artifacts” and video work.

One third of Hinkle’s exhibition is devoted to The Kentifrica Project, an ongoing ethnographic exploration of the “contested geography/continent” of Kentifrica (“Kentucky” plus “West Africa”). Previous iterations of the project have included serving Kentifrican food, inventing (like Roseborough) a Kentifrican alphabet and telling Kentifrican myths.