Atlantic and Pacific

The painting is dedicated to the completion of the Panama Canal, which opened in 1914. The faster trade route to the East Coast and Atlantic Ocean was a huge boon to the West Coast economy and brought the region’s goods into more global markets.

“It was an important moment in America’s history, where it was defining itself as a world power,” says Anthea Hartig, director of the California Historical Society.

At the center of the oil on canvas mural, a Herculean man rises out of the water. Ganz believes he is meant to represent the Panama Canal or the labor that produced it. He supports an ethereal couple, emblematic of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. “It’s the marriage of the seas,” says Ganz.

The figures populating the right and left sides of the painting represent the East and West. Dodge’s depictions of both are typical of his time. The eastern figures wear colorful costumes, carry bright flags and lead an elephant. The west is made up of workers, farmers, miners and oxen.

The one discordant note in the whole painting is a figure with his back turned to the viewer and his arms held up in the air. The western oxen seems about to push him into the canal.

“He represents Native American culture, which was essentially being wiped out with westward expansion. That is also one of the themes of the PPIE and one of the darker themes of Manifest Destiny,” says Ganz.

The International Exposition

Before the internet — people had fairs. Fairs brought the wonders of the world to the people. And at the turn of the 20th century, it was a monumental undertaking to bring international innovations, arts and culture together.

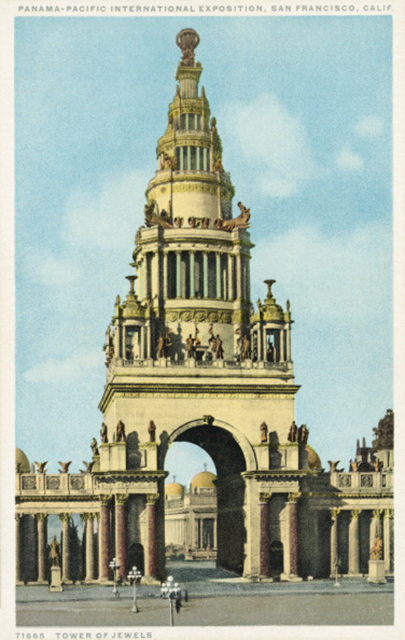

In 1904, when Congress announced a competition to host the Panama Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco officials jumped on the opportunity. But just two years later, the 1906 earthquake and fire razed the city.

“The city was still smoldering when [San Francisco officials] held a dinner and recommitted themselves to winning the fair. And they did. They poured all this civic, entrepreneurial and collective energy into both raising money and designing the fair,” says Hartig.

Hartig credits the fair with helping San Francisco recover after the devastation of 1906.

The fairgrounds extended from Crissy Field to Fort Mason, covering around 635 acres. Preparing for the exposition created an abundance of work in a variety of fields, from construction to the arts, advertising to publishing, carnival rides and brothels.

“This fair’s monumentality was marked in my mind as a historian because it was so thoroughly modern,” says Hartig.

New technologies were on display. The fair featured planes, cross-country telephone lines and a fully functional Ford Model T assembly line.

Today at the de Young, the mural provides a glimpse into the mindset of PPIE fairgoers 100 years ago; as they viewed Dodge’s painting, they stood among the newly-constructed buildings of their recently-devastated city, celebrated a momentous feat of engineering and marveled at the possibilities this union of Atlantic and Pacific might bring to San Francisco.

For more about San Francisco’s year-long celebration of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, visit ppie100.org.