In George Jones’ rollicking track Wrong’s What I Do Best, the singer claims, “I’m just trying to find myself / Before I get too old.” But ones’ search is just a ruse, as he’s got himself pretty much figured out — he’s an outlaw, a loser, a seeker of “blues and bad news.”

For his first curatorial effort at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), Hesse McGraw, the Vice President for Exhibitions and Public Programs, joins forces with artist Aaron Spangler to gather an impressive exhibition of fifteen contemporary artists and collaboratives. Like Jones, the artist personas represented are outrageous, excessive and elusive. For Wrong’s What I Do Best, it’s all about the story, truth (and intention) be damned.

The installation begins just outside the Walter and McBean Galleries. To the right, floor to ceiling mirrors reflect visitors back at themselves. This show is about personhood — there’s no escaping it. The exhibition guide includes quotes from each artist instead of descriptive text or curatorial statements. In some instances, the quotes line up so well they actually call attention to details in the works. For instance, Trenton Doyle Hancock is quoted saying “I want to show that I’m not trying to cover up anything any longer.” In the top right corner of his painting, A New Creature #1, a small hole exposes the stretcher bar behind.

The visual overload of Hancock’s work is matched, and possibly exceeded, by Ashley Bickerton’s contributions, which are best described as large-scale assemblages of natural and man-made overabundance. With their open mouths, prominent tongues, and enlarged, glossy eyes, her female heads are witchy representations of pure abandonment.

Upstairs, Jonathan Meese’s painting We Toll… features a central figure, staring, on a canvas of thick abstract expressionism (echoed nicely in CLUB PAINT’s contributions), iron crosses on either side of her head and flames rising from below. To the right of Meese’s painting, Brad Kahlhamer’s Desert, Forest, City is a densely populated drawing of bloody spatter, skeletons, girls in pigtails, and birds of prey. The horror vacui within both Meese and Kahlhamer’s works is echoed by the artists themselves. “In art you can never go too far,” says Meese. Kahlhamer’s stated goal is to “go completely wildcat, totally unauthorized, and let’s see what happens.”

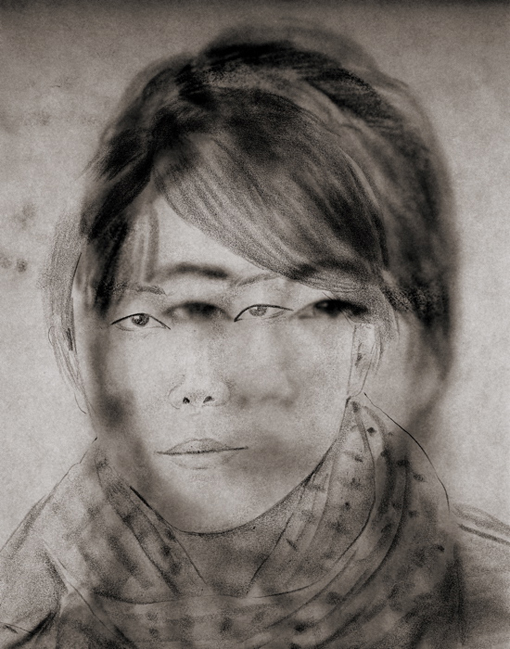

Other aspects of the show are less overtly off-the-rails. Three Dana Schutz works give mysterious narrative shape to improbable situations, including two charcoal drawings from 2014, cubist scenes crowded with nefarious figures. Marianne Vitale’s sculptures are by turns inexplicable and confrontational: a series of bronze Douche Bags are scattered about the main gallery floor.