Books have an ability to transport us outside of our lives. They can take us to other times, other countries, places we might never go — from Teddy Roosevelt’s time as the Police Commissioner of New York in the non-fiction work Island of Vice to the book-haunted Barcelona as crafted by Carlos Ruiz Zafón in his novel The Shadow of the Wind. Books are the easiest means of space travel, whether we join Neil deGrasse Tyson in Space Chronicles on a tour of the actual solar system or Frank Herbert to visit the imagined world of Dune.

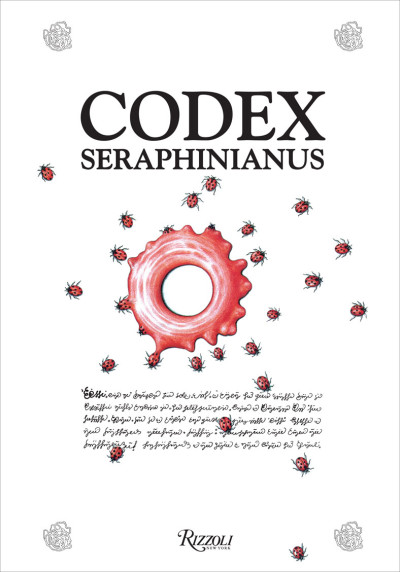

But even books that transport us to worlds other than our own seem to be clearly from our world. That’s not the case with the legendary work that calls itself Codex Seraphinianus, with the byline of Italian artist and architect Luigi Serafini. The book itself is shrouded in mystery, and the content manages to capture the impossible on the printed page. It’s a book in a language that does not exist about a world that could not exist.

Codex Seraphinianus is indeed real, though most who have heard of it know it more from rumor and second-hand description than actual experience. The original publication in Italy was in 1981, in two volumes; copies now fetch in the neighborhood of $5,000 to $10,000. An American version was published by Random House in one volume in 1983; one of these may set you back some $2,000 to $3,000. Even subsequent paperback copies cost $500 to $700. There’s a good reason that this book is more fable than fact in the minds of those who have come across word of it.

But late last year, that changed, when the author, working with Rizzoli Publishing in New York and Milan, issued a new edition, in a gorgeous, beautifully produced hardcover, with new illustrations, new “text” and even a short “De-Codex” describing the creation of this iconoclastic masterpiece. At $125, it’s a bargain, this book not only about a world that does not exist, could not exist; yes, the Codex Seraphinianus is still clearly from a world beyond human imagination.

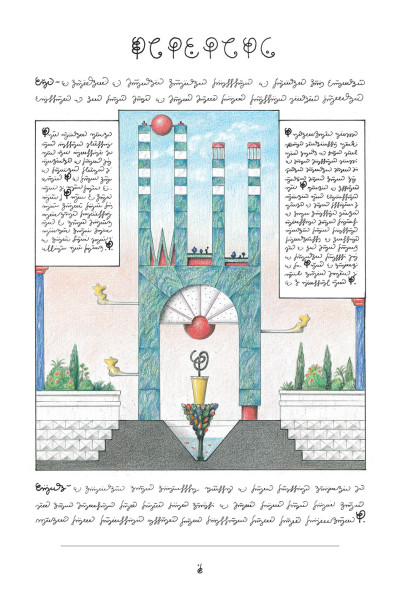

The book takes its cues from the most ancient encyclopedias; Pliny’s Nautralis Historia and De Rerum Natura by Lucretius. To accompany his surreal illustrations, Serafini created his own language, for a very specific writerly reason.