In the late 90s, before Dave Eggers wrote a bestselling memoir (A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius), before he penned the screenplay for Where the Wild Things Are, before any of his novels, he was a young guy sitting in his kitchen tearing open envelopes filled with literary submissions.

They were “mostly articles that had been killed from larger, more reputable magazines and journals,” Eggers tells Morning Edition‘s Renee Montagne. “So it was sort of a land of misfit writings, I guess. Pieces that were too strange, too untimely, too short, too long, too experimental.”

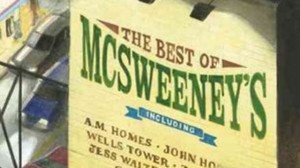

But they were perfect for a quirky new literary magazine he was putting together: Timothy McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, which celebrates its 15th anniversary this year. To mark that milestone, Eggers has published a hefty Best of McSweeney’s anthology — several hundred pages thicker than the first issue of McSweeney’s, which bid the reader, in old-fashioned print, “Welcome to our bunker!”

“I was working at some bigger magazines at the time, and this was sort of a reaction to sort of bring it back to the text only, and make a very uncomplicated journal that was a little bit of a throwback,” Eggers says. “I collected a lot of pamphlets and Bibles and medical reference books from the 17th, 18th, 19th century and there was that kind of intimacy in a lot of these books that would speak directly to the reader, like, “This is the greatest book that you have ever owned! It replaces all other texts!” You know, “Read nothing else!” I mean, there was a real kind of intimacy and, at the same time, kind of a blustery salesmanship to those journals, and so I was kind of playing on that for a while.”

Over the last 15 years, McSweeney’s has grown into something of a literary empire based in San Francisco, and that flagship literary quarterly has evolved from a plain-looking throwback to the 19th century, to an intriguing array of eye-popping designs and visual puns. One issue came out in the form of a pile of junk mail. Another contained a short story printed on giant playing cards — readable any way the cards were dealt.

9(MDAzOTIwODA0MDEyNTA4MTM1OTcyMGJmMA001))