Four months ago, a very large earthquake occurred beneath far easternmost Russia, but not even the locals paid it much notice because it was far away from everyone—609 kilometers (378 miles) straight down from a point in the Sea of Okhotsk. Within the hour, though, seismologists around the world were buzzing because it appeared to be a record-setting event. A paper published in Science today confirms that the May 24 Russian quake was the largest deep earthquake ever recorded, and also shows that it was quite different from the previous record-holder, a 1994 event 637 kilometers beneath Bolivia.

The world’s deepest earthquakes don’t make much of a ruckus in human terms, but seismologists are deeply interested in them because they’re not supposed to happen. Rocks soften as they heat up, and at depths below around 50 kilometers they’re generally so hot that they flow instead of breaking. No rupturing means no earthquakes. That’s why the San Andreas fault just peters out at its base, and it’s a major reason why the Earth’s outer shell can slide around in continent-sized pieces called tectonic plates.

Nevertheless, somehow certain rocks can rupture and release stress—creating earthquakes—as deep as 700 kilometers, the boundary between the upper and lower mantle. So deep quakes are potent clues to interesting science in a part of the earth where we have almost no direct evidence. Deep quakes happen where plates are being pulled down into the mantle in the process called subduction. Subducting plates are naturally much colder than the rock around them, so the general thinking is that they remain brittle to a greater depth. But the details are still puzzling.

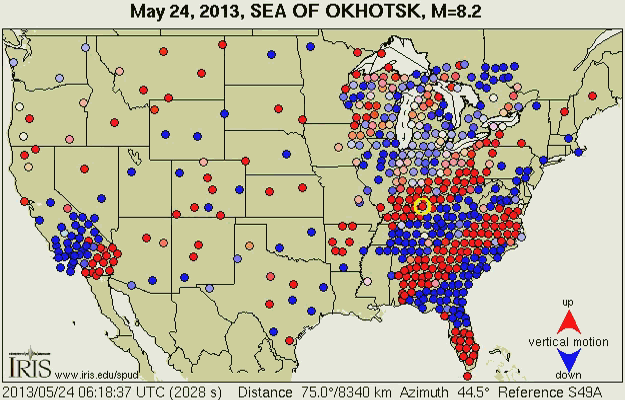

In the Science paper, a team including UC Santa Cruz’s Thorne Lay and his graduate student Lingling Ye assigned the 2013 Russia quake the same magnitude, 8.3, as the 1994 Bolivia quake. But in fact it had one-third more energy, just not enough for an 8.4. So that was a nice thing to learn. The team relied on the excellent data from the USArray network, a decade-long experiment that’s been stationing large groups of seismometers around the country in a gigantic version of a doctor positioning a stethoscope on a patient’s body. Here’s a snapshot of the seismic waves from the 2013 quake sweeping from Russia across the USArray.

Ye and Lay’s team mapped the deep rupture as a large, nearly horizontal fault inside the subducting plate. They were able to determine that the upper side of the fault slid and scraped over the bottom side more than 30 feet (9.9 meters) in 30 seconds. They detected only a few small aftershocks, but that’s common in deep earthquakes—the long-lasting aftershock sequences familiar in shallow quakes are muffled in these deep-seated rocks.

Compared to the 1994 Bolivia quake, the 2013 Russia event was much louder—that is, it sent out more of its energy as seismic waves. The speed at which the rock ruptured was four times greater in Russia than in Bolivia. And the amount of stress released at a given spot was much smaller in Russia than in Bolivia. In these respects the Russia quake resembled shallow earthquakes.