The U.K.’s fraught decision to exit the European Union was motivated by everyday issues such as trade and immigration. But its impact could soon be felt in some of Europe’s most esoteric locales — like particle accelerators.

That’s because scientists in Europe pool their resources to build everything from massive telescopes to deep space probes. And the U.K. is a major scientific player. Britain’s vote to depart the European Union won’t totally upend scientific cooperation, but “scientists are nonetheless worried,” says John Womersley, the head of the U.K.’s Science and Technology Facilities Council, which oversees participation in large projects.

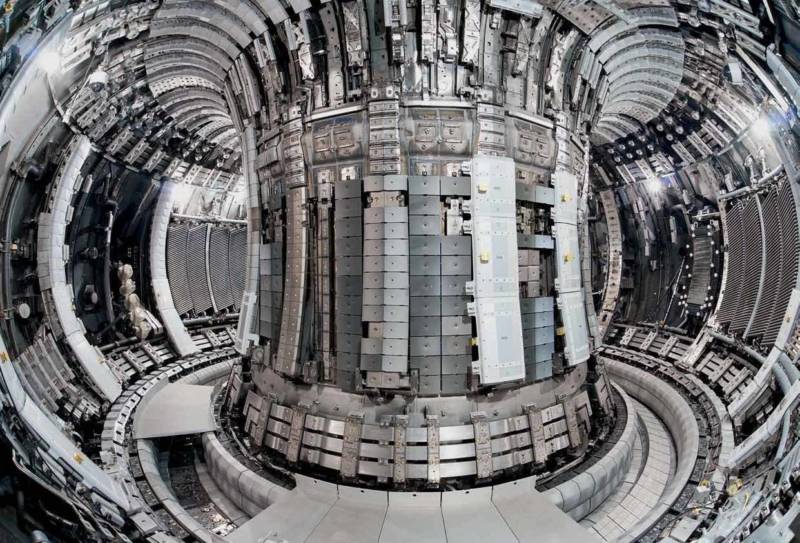

The biggest experiment affected is a nuclear fusion reactor being built in the south of France. Known as ITER, the roughly $20 billion project is designed to produce energy through the fusion of light atoms of hydrogen. It’s an unprecedented technical endeavor that involves seven international partners, including the European Union, which is shouldering some 46 percent of its construction cost.

The project is already suffering from massive cost overruns and schedule delays, and Brexit is just adding to the worries. Although a complete U.K. withdrawal from the project is unlikely, there is no plan in place for post-Brexit participation, says Steven Cowley, who heads the U.K.’s Culham Center for Fusion Energy, which is a major center for ITER R&D. “We are rudderless at the moment,” he says.

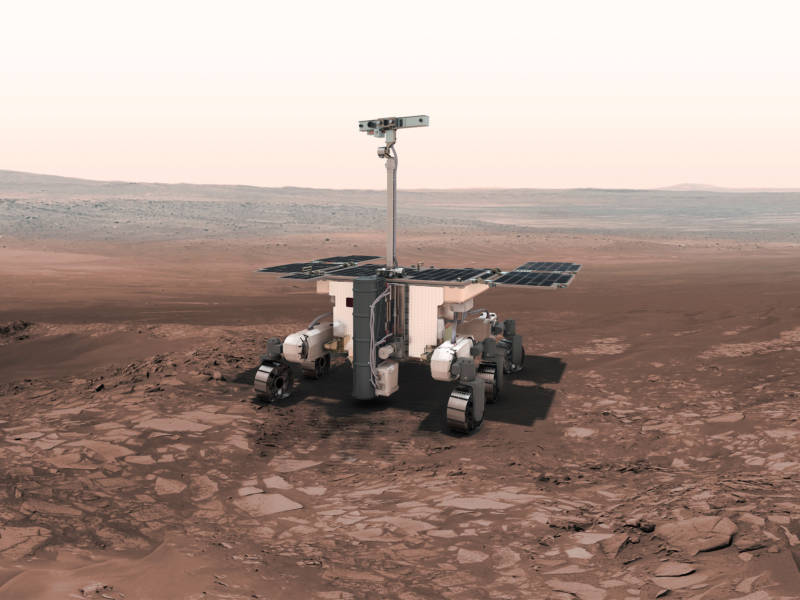

U.K. cooperation in other projects is more clearly defined. Many scientific organizations, such as high-energy physics laboratory CERN, based in Switzerland, and the European Space Agency (ESA), were actually formed before the European Union. British membership in these organizations would not be directly affected, but its role could change.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))