Image: Sanofi Pasteur via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

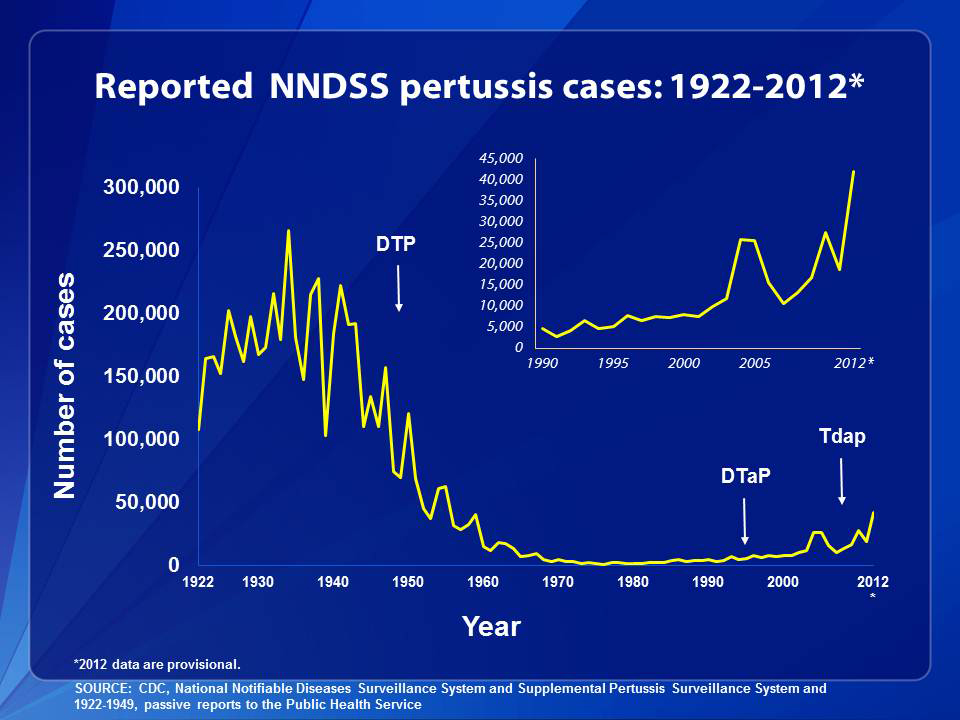

In 1976, public health officials celebrated when whooping cough cases dropped to 1,010—the fewest ever reported. Before widespread vaccination against whooping cough, the disease infected up to 270,000 people a year, killing as many as 10,000, mostly infants. Just five years earlier, widespread vaccination against smallpox had worked so well that health officials retired the vaccine, raising hopes that whooping cough might follow a similar path. But whooping cough, or pertussis—named after the pathogenic bacterium Bordetella pertussis—has proven a far more formidable opponent.

In recent years, despite relatively high vaccination rates, the pathogen has come roaring back to infect people in numbers not seen since the pre-vaccine days. Several states suffered outbreaks last year, with more than 41,000 cases reported across the country. California’s epidemic hit in 2010, when more than 9,000 people fell ill—the highest number in more than 60 years—and 10 infants died. Pertussis has also rebounded in Europe. England and Wales saw a record number of cases in 2012, with more than 9,700 cases and 14 infant deaths.

Pertussis attacks the respiratory track to cause spasmodic coughing, vomiting and severe breathing problems as thick mucus clogs the lungs. Most deaths occur in babies because the buildup of mucus quickly overwhelms their still-developing blood vessels, depriving their lungs of oxygen. “It’s like they’re being strangled to death by this particular bacteria,” pediatrician Paul Offit says of watching a stricken child.

Although vaccination protects infants, babies younger than two months old—too young to receive the first of five recommended vaccinations—face the greatest risk of death. Nine of the 10 children who died during the California epidemic were less than two months old.

Several factors may account for recent pertussis outbreaks, including waning effectiveness of the vaccine, the evolution of more aggressive pathogens, a mismatch between the vaccine and the bacterium and increased awareness among health professionals. Following the California epidemic, researchers at Kaiser Permanente’s Vaccine Study Center tested the waning immunity hypothesis: the possibility that protection from the vaccine fades with time.

Before vaccines targeting B. pertussis were introduced in the 1940s, pertussis was a major cause of infant death worldwide, killing more children than polio, measles and tuberculosis combined. The original pertussis vaccine was made from killing the bacteria with chemicals, and combining the whole bacterium with weakened diphtheria and tetanus toxins in a vaccine called DTwP— “w” for “whole cell.” After concerns about the vaccine’s adverse effects—both real (episodes of high fever, fever with seizure, irritability, and a scary though short-lived condition called hypotonic hyporesponsive syndrome, in which children appear limp, unresponsive and pale) and unsupported by science (long term brain damage)—led to rising rates of vaccine refusal in the 1980s, vaccine developers formulated an acellular vaccine, DTaP, using isolated components of the pathogen.