Scientists have found that an elusive millipede species near San Luis Obispo can actually glow. These millipedes were first—and last—seen in 1967, but no one knew that they glowed until their rediscovery in 2013.

Remarkably, in that same year students from UC Davis discovered glowing millipedes on Alcatraz Island, crawling quietly around the famous penitentiary.

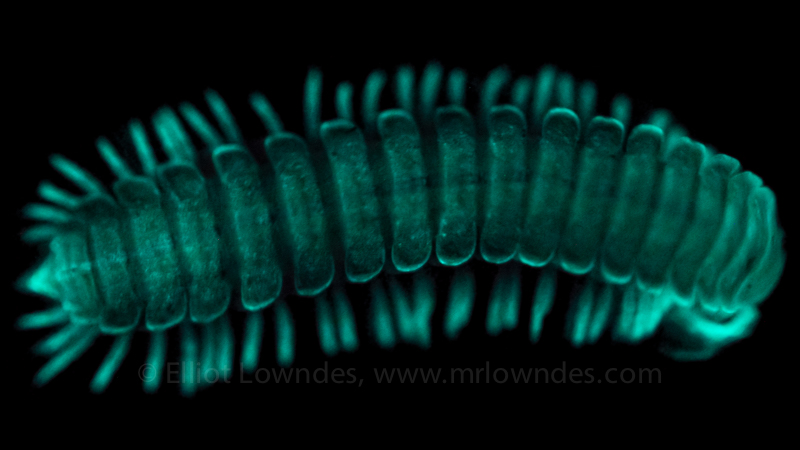

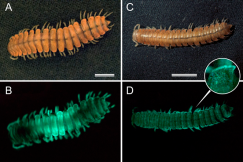

However, the two glows are completely different. The Alcatraz millipedes are fluorescent, which means they shine only when illuminated with a blacklight.

Fluorescence is often seen in millipedes. According to UC Davis undergraduate researcher Alexander Nguyen, the animals on Alcatraz belong to a well-known Northern California species. And the new species from San Luis Obispo (SLO) is likely to fluoresce too. But the SLO species can also produce its own light from scratch, a process called bioluminescence.

Though bioluminescence is rare among millipedes, California is relatively rich in such luminous species. The SLO species is the eleventh California luminous millipede—and has the faintest glow of all. That might seem disappointing, but the animal’s very dimness offers a key to the long-standing puzzle of how luminescence evolved in this group. Entomologists Paul Marek of Virginia Tech and Wendy Moore of the University of Arizona published a study on May 4th in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showing that the millipedes’ glow actually began as a way to cope with California’s dry heat.

California luminous millipedes are all just a few centimeters long, shorter than your finger. Blind and nocturnal, they live in mountain forests and meadows, where they keep to a steady diet of moldy leaves. But they’re not completely harmless—as a defensive measure, their pores ooze cyanide. Their characteristic blue-green glow is thought to warn potential predators about this deadly poison.