Coral-reef islands, those sandy staples of tropical travel brochures, are also a geological puzzle of long standing. How can they remain above the sea in the face of tropical storms or rising sea level? A new study in the Indian Ocean singles out coral-crunching fish as a key player.

The Maldives are a group of more than a thousand cays, or low-lying sandy islands, within a large coral reef in the tropical Indian Ocean. These islands stabilize as storm waves throw sand up onto the beach, where the wind can move it around and pile it up into dunes. From there it’s just a matter of vegetation setting root to hold the sand in place as dry land.

The question that follows, then, is how does a reef make sand? The answer varies. The geologist knows that ordinary beach sand is made as erosion breaks rocks into tiny bits. But reef sand or coral sand, instead, is almost entirely made of bits of seashells and other carbonate-mineral stuff. This is material that living things have chemically extracted from the dissolved minerals in seawater.

Reefs, then, owe their sand to various living organisms. In some reefs, one-celled organisms (benthic foraminifera) secrete tiny mineral shells around themselves that become ready-made sand. Other reefs have their sand supplied by algae of various kinds, either green calcareous algae of the Halimeda group or red coralline algae. The reefs of the Maldives are forests of big, stony corals, but these don’t make much sand, even when large waves break them up.

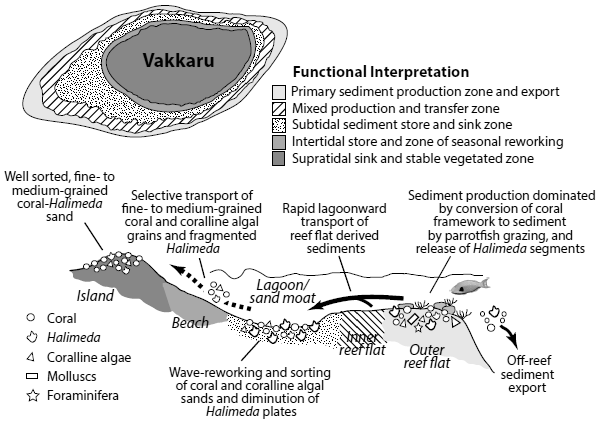

Chris Perry, of the University of Exeter, is a leading researcher in this field. For his new study, just published in the journal Geology, he and a team of researchers visited a little reef island in the Maldives named Vakkaru.

Perry’s research team mapped the ecosystem and the sediments around Vakkaru, taking care to sample each zone of the reef, from the outer flat to the pristine white beach.