Geologists are familiar with something most of us have never seen—spherules, or microscopic balls of natural glass that hide in sediments all over the world. A new study reports a previously unknown kind of spherule that’s forged during volcanic eruptions as lightning lashes roiling clouds of hot ash.

Glassy spherules occur in all kinds of places on Earth, and on the Moon, and we know several ways they’re created. Meteors make them as they burn up entering the atmosphere from space. Large meteor impacts make lots more spherules as they explode into fiery debris. The same impacts can melt the ground they strike and form tektites. The red-hot spray of exploding lava also can make spherules, called Pele’s spheres or achneliths. All of these spherule types are on the order of a millimeter across.

And we have lightning. Whether it strikes loose sediment or hard stone, lightning’s instantaneous heat, estimated at 30,000°C, can melt tubes and droplets of material into the curious features called fulgurites. Knowing this power of lightning, Kimberly Genareau, a volcanologist at the University of Alabama, wondered what happens in eruption clouds of volcanic ash when lightning laces through them. What she learned is the subject of an open-access paper in the journal Geology.

She acquired ash from two eruptions known for their spectacular volcanic lightning displays, the 2009 eruption of Redoubt in Alaska and the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajokull in Iceland.

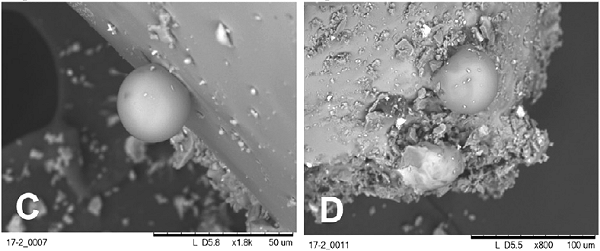

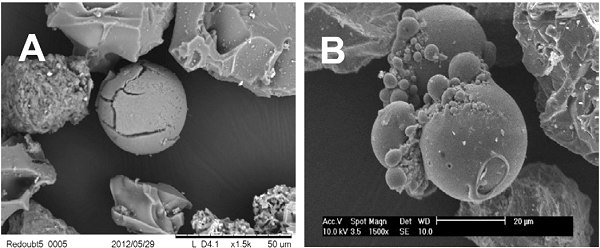

The ashes contained a noticeable share of glassy spherules, as much as a few percent. These looked different enough from other types of spherules for Genareau and her coauthors to declare them a new type with the workaday name of lightning-induced volcanic spherules, or LIVS.

To create spherules themselves in a laboratory setting, Genareau turned to industrial techniques. Volcanic ash does nasty things to human equipment. It scratches car windshields, clogs air filters and damages jet engines. Electrical substations rely on the insulating property of air to prevent short circuits between high-voltage fixtures, but volcanic ash mucks that up badly.