Researchers from Stanford University School of Medicine believe they’ve found a drug for cardiac stents that can more effectively prevent stent complications.

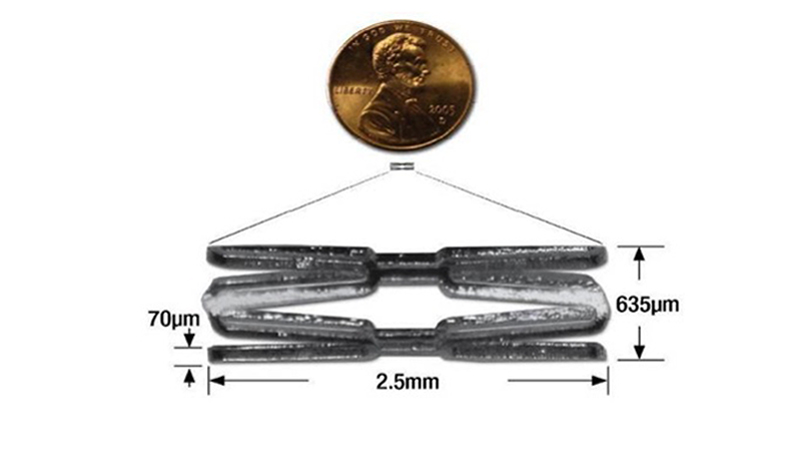

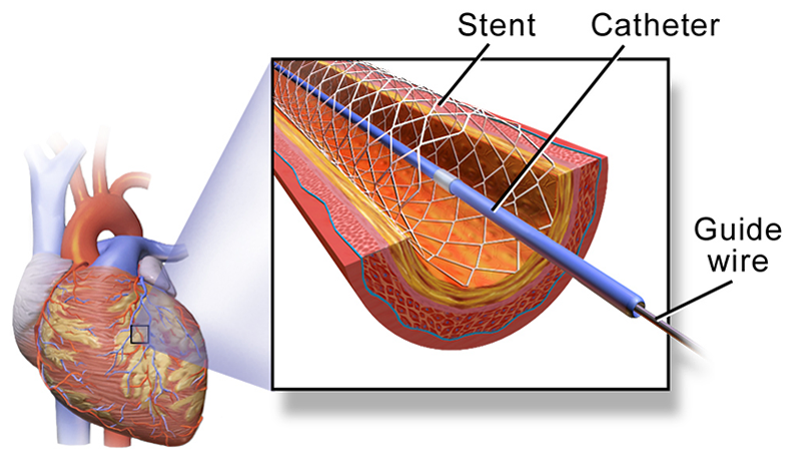

Over a million people in the U.S. each year undergo angioplasty heart surgery using a drug-coated stent to treat blocked arteries, according to the American Heart Association. A stent is a tiny wire mesh tube that is permanently implanted into the artery at the blockage point, creating a scaffold that props open the artery to reduce the chance of a heart attack. However, placement of bare metal stents can themselves damage the artery lining, causing scar tissue to grow and narrow the artery. Known as in-stent stenosis, this typically occurs 3-6 months after the surgical procedure and can lead to chest pain and even heart attacks.

To help prevent in-stent stenosis, doctors use stents coated with drugs that inhibit tissue regrowth to help prevent the blood vessels from reclosing. Unfortunately, these drugs can also inhibit beneficial regrowth of the vessel’s blood lining (endothelium) that aids the healing process. So patients still need to take blood-thinners for up to a year to reduce the risk of a blood clot developing in the stent and blocking the artery. This need for blood thinners is a serious problem for many people with other health issues; for instance, it means they can’t have surgery while taking the medication.

Stanford researchers have now identified a drug to coat cardiac stents that helps prevent in-stent stenosis without affecting the healing of the blood vessel lining. Their new research is described in a paper published this month in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. Dr. Euan Ashley, associate professor of cardiovascular medicine and genetics at Stanford University Medical Center, led the research team.

The researchers first sought to more fully understand the genetic pathways of coronary artery disease using a “big data” computational biology approach. Using data from previous studies, they analyzed large datasets of coronary artery tissue samples and genome information from patients who had developed in-stent stenosis after undergoing angioplasty and stenting. Based on network analyses, the researchers hypothesized that there is an increased risk of in-stent stenosis due to the interplay of two genes, GPX1 and ROS1.