When the Bay Area’s next big earthquake strikes, forecasts say that more than 150,000 housing units will be permanently lost and their residents made homeless—as things stand now. The majority of those earthquake refugees will come from one class of structure: small wood-framed apartment buildings with soft stories. Cities are now targeting these weak points in the urban fabric. Oakland, the Bay Area city with the greatest length of major fault lines in its borders, is joining Berkeley and San Francisco with a major strengthening program for soft-story apartments.

It takes time to prepare a region against deadly earthquakes. A million things need attention, and most of them involve fixing structures that weren’t built with earthquakes in mind. In the 25 years since the Loma Prieta quake, Bay Area agencies have taken care of the big-ticket items. Caltrans has beefed up the big bridges and all the freeway overpasses. BART has strengthened its tracks and stations. The water agencies have fixed their largest mains wherever they cross a major fault line. The power and gas systems are much more robust today.

Once a city’s lifelines are able to survive an earthquake, the next step is to see that residents can quickly resume their lives—with homes, schools and jobs. Schools are seismically strong, thanks to the Field Act of 1933. Modern business buildings meet strong codes and should be quickly repairable. Streets are straightforward to fix. Living places are the weakest link, and Oakland has been working on a program for several years to retrofit vulnerable residences.

The biggest payoff is in fixing soft-story apartments—buildings with ground floors occupied by parking spaces or retail shops. When one of these building slumps, everyone in it is displaced, the building is ruined and its neighboring properties are jeopardized. The Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989 brought down many of these in the Marina district of San Francisco, and in Oakland some 1300 residence units of this type were lost or severely damaged—and in those cities that did not count as a major quake.

It pays in many ways to preserve them instead. Oakland’s city administrator, Henry Gardner, made a succinct case for a retrofit program in a recent memo to the City Council:

Retrofitting soft-story apartment buildings will likely save lives, minimize injuries and help keep people in their homes after a major disaster. Renters can avoid personal losses, costs associated with relocating, and inflated rental prices. In particular, retrofitting soft-story apartment buildings will protect the most vulnerable, the same people most at risk of being displaced after a disaster. Building owners can avoid the cost of demolishing and rebuilding, and avoid revenue loss while rebuilding occurs. The public sector can avoid the cost of emergency services for disaster housing, and the loss of tax revenue from rental property owners. Additionally, retrofitting soft-story apartment buildings aligns with Oakland’s sustainability goals by reducing the City’s post-earthquake carbon footprint.

It also must be said that these buildings are an important part of Oakland’s heritage and character. Many of them were built in the 1920s, and they dominate cherished neighborhoods all around Lake Merritt as well as the Dimond, Laurel and East Lake.

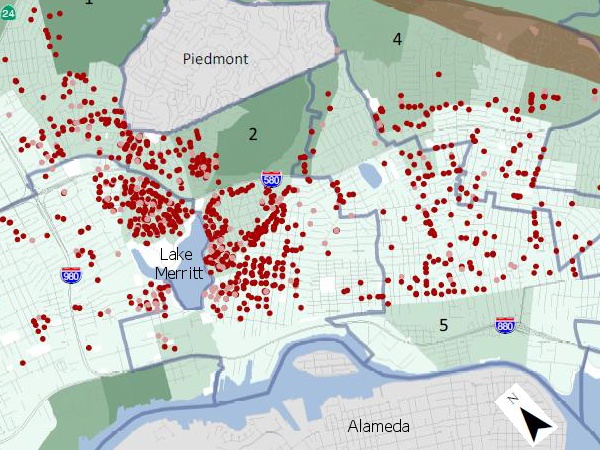

Oakland started its focus on soft-story apartments in 2008 with a preliminary survey that mapped 1400 of these buildings, then a 2009 ordinance requiring their owners to assess their structures. Now it’s ready to move ahead with a formal Soft Story Retrofit Program that will be presented to the City Council in a few months. Its basic elements are becoming clear, but the details are fluid. Building owners and residents will share the cost of retrofits, and a long menu of possible incentives will be considered. There is seed money available. (More details are given in Gardner’s memo.)