The South Napa earthquake that occurred on August 24 was on everyone’s mind as the Third International Conference on Earthquake Early Warning convened last week in Berkeley. The meeting was a powerful show of scientific and political momentum as California prepares to lead the United States into a brave new world in which we’ll get second-by-second countdowns in advance of dangerous earthquake shaking. Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom assured the conference that the money for the early-warning system will come: “It’s a political question, not a financial question.”

“Early warning” is not a prediction of an earthquake, but rather an instant notification that an earthquake has started and shaking is on its way. Several nations have early-warning systems in place, and California scientists have been working on an American version on a shoestring of funding. Today they’re ready to roll with a plan based on ShakeAlert, a beta-tested system that includes a smartphone app.

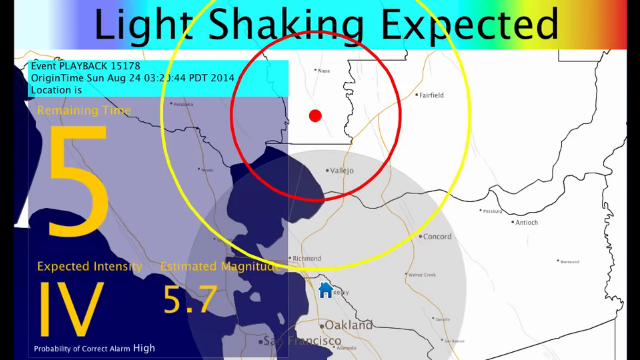

On August 24, an alert reached the phone of beta tester Richard Allen, head of UC Berkeley’s Seismological Laboratory. Because he was in Southern California at the time, the app awakened him at 3:20 a.m. with a series of alarm tones and a male voice calmly saying that “no shaking will arrive in approximately 200 seconds.” But at Berkeley, the app said that light shaking would arrive in 5 seconds—and so it did.

After more then two years of testing, California is ready to turn this beta into a prototype, then a rollout for a lot of people who are eager to use ShakeAlert for real—firefighters and other emergency responders, managers of large buildings and critical facilities, computer admins and earthquake geeks. Experts from other countries are eager to share their knowledge with us. All of those people were represented at the three-day conference, where they’d gathered to see and discuss the future.

The mechanics of ShakeAlert are ready to go. The U.S. Geological Survey, which has funded this line of research for over 20 years, published Open-File Report 2014-1097 in May, a detailed plan to complete the system. USGS representatives explained that this plan constitutes a pledge to build it when the money, about $80 million over five years, is in hand. It will look pretty much like the beta version, although researchers will continue to refine every part of it during implementation.