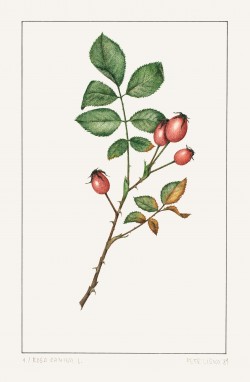

Botanical art usually makes people think of flowers, but in fact, scientific illustrators routinely document and find beauty in every part of the plant, stem and root, leaf and fruit. That includes what may seem to be the least attractive botanical anatomy: thorns, spines, and prickles.

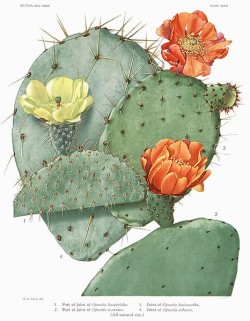

These defensive structures are rampant throughout California’s vegetation, both native (like prickly pear and agave) and invasive (like foxtails and teasel). Such fierce subjects have inspired many of the state’s widely-known botanical artists, including Jeanne Russell Janish, the first woman to get a geology MA from Stanford. Several inspired illustrations will be featured in a new exhibition called “Dangerous Beauty: Thorns, Spines and Prickles,” opening September 18 at CMU’s Hunt Institute in Pittsburgh.

It may come as a surprise that thorns, spines, and prickles are each anatomically distinct achievements in sharpness.

Spines are simply modified leaves. Thorns, however, grow from stems, and like any plant stem they can branch and grow leaves. Both spines and thorns are as much a part of the plant’s body as your finger is of yours; they are hooked in to the plant’s internal transport system just like your finger is wired up with blood vessels and nerves. Prickles, meanwhile, are more like fingernails—mere extensions of the plant’s epidermis with no deeper connectivity.

These precise botanical definitions are often at odds with informal terminology, leading to contradictions such as the prickly pear cactus. It has no prickles.