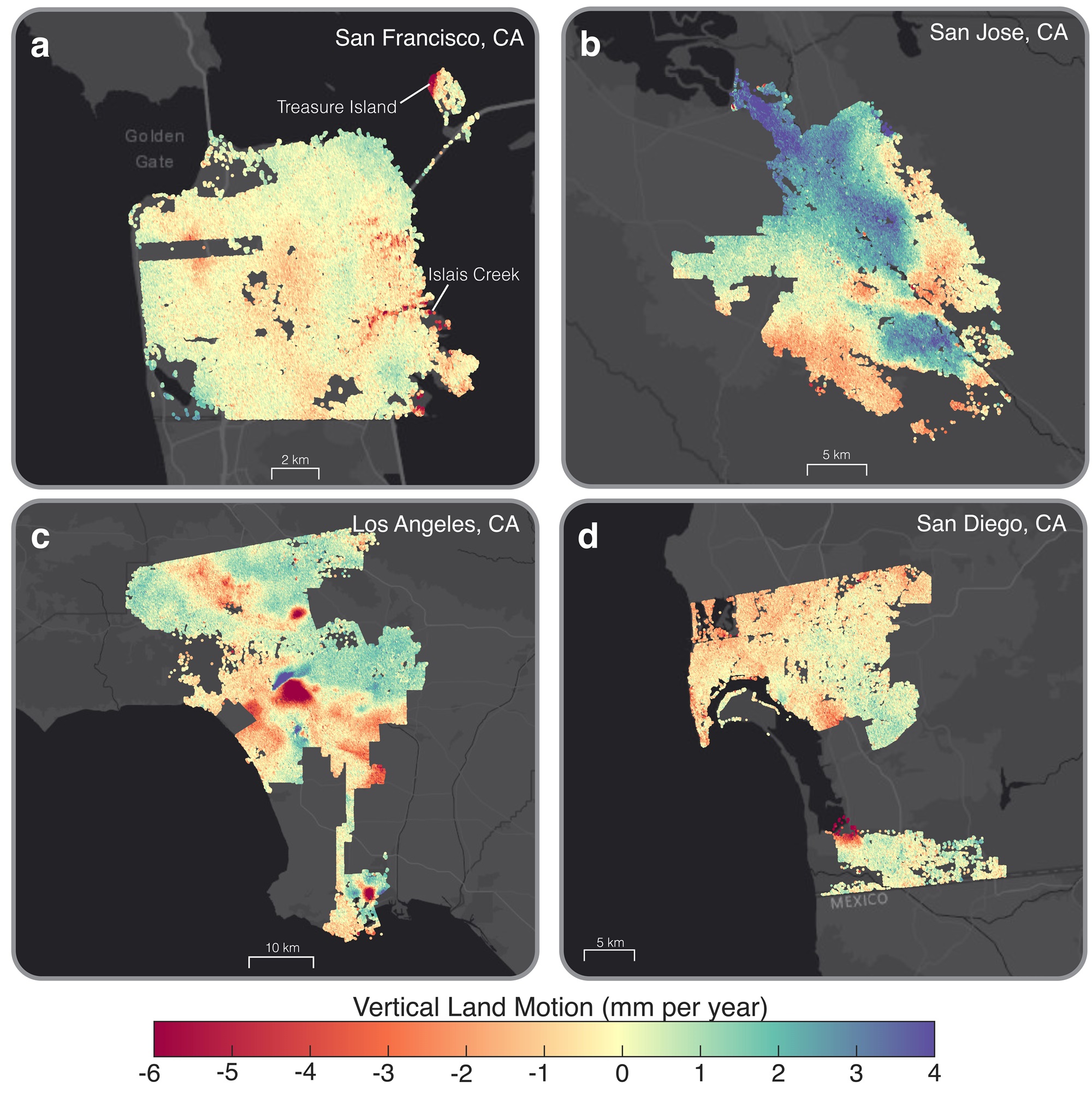

The slow sinking of the nation’s biggest metropolitan areas — including parts of San Francisco — poses a growing hazard with vast socioeconomic consequences, researchers said in a new study.

Because the sinking areas are usually in the densest parts of cities, as many as 34 million people could be affected and 29,000 buildings could be at high risk of damage, according to the study published this week in the journal Nature Cities.

Using satellite data from 2015 to 2021, the authors looked at 28 U.S. cities with populations over 600,000 and found that in every one, at least 20% of urban areas are sinking — but in 25 of the cities, at least two-thirds of their area is subsiding. This phenomenon, often caused by overpumping groundwater, can increase flood potential.